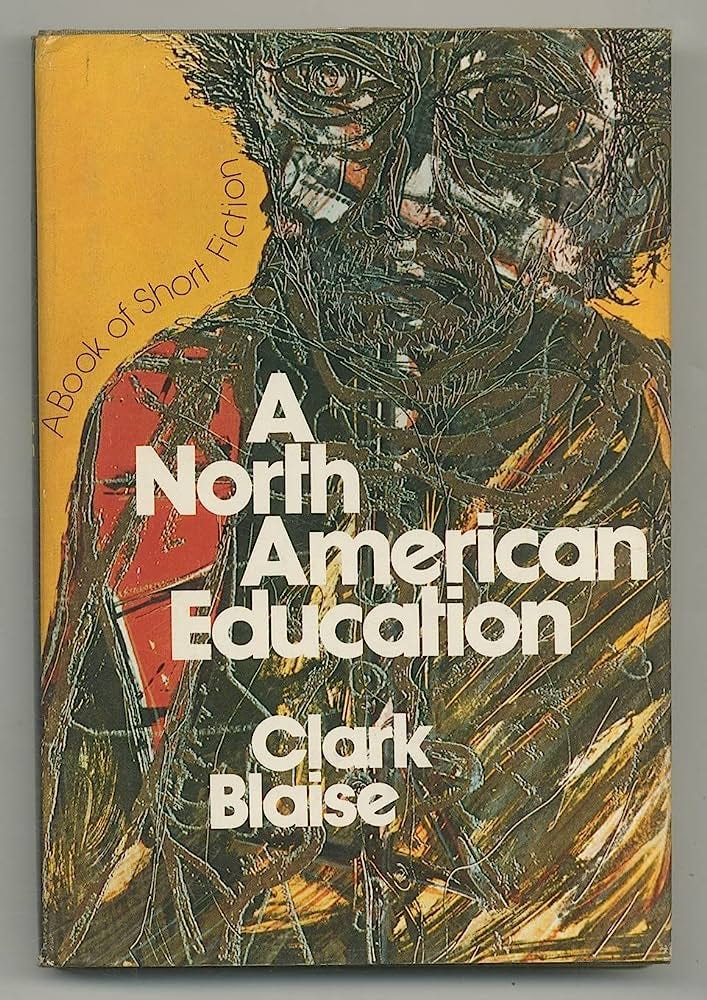

This is a taste, the opening paragraphs, of my essay on Clark Blaise’s early short story “A North American Education” — essay just out in the magazine Canadian Notes and Queries. CNQ is published by Biblioasis, the publisher of two of my essay books, The Erotics of Restraint and Attack of the Copula Spiders, and over the years I have contributed a number of pieces to the magazine.

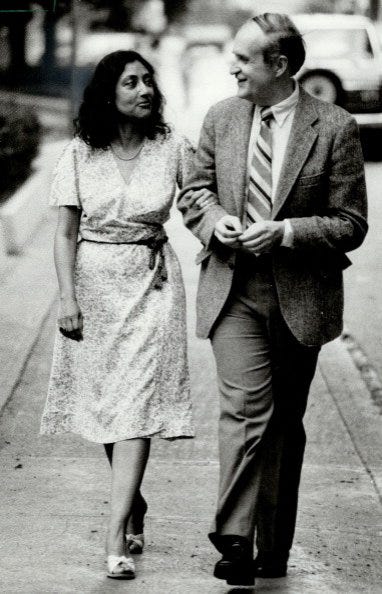

Clark Blaise and I also have a history. Back in the early 1980s, he and his wife Bharati Mukherjee were teaching at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, but they also had an alternating gig at the Iowa Writers Workshop. I met Clark in Iowa, must have, though I can’t recall the occasion. But in 1983, my then girlfriend Peggy Gifford got a job interview in New York. On our way there, we stopped in for an overnight at Clark’s fantastic mansion on Circular Street in Saratoga. Next day we drove on to New York, but the job interview was a bust. With not much else to do and little money, I headed back to Saratoga and took up residence in one of Clark’s spare rooms (there were probably a dozen spare bedrooms). I took over a little conservatory at the side of the house where I did my writing. It was just Clark and I in residence; Bharati was doing her stint in Iowa.

Soon Peggy drifted back as well. She had found a parttime gig at the Feminist Press but wasn’t making enough to afford an apartment. We stayed with Clark for free and she commuted to the city every week, couch surfing with friends. We were the original bad guests, the ones who never leave. Though, of course, Clark was a gentleman, and, I think, quite happy for the company. I can still vividly recall stumbling downstairs of a morning and finding Peggy and Clark in their bathrobes in the kitchen, drinking coffee and reading the Times.

We stayed in that house so long that we helped Clark pack when he put the place up for sale and moved on to Iowa. He even left us enough furniture to get by on. We stayed on until the sale went through. Looking back, I can’t really imagine how it happened. It was an awfully big house, with uncountable Skiddies living like rats in the attic rooms and an octagonal garage in back with a mechanical floor that would automatically turn your car around so you could drive straight out. Above the garage was an octagonal apartment where the mansion’s original owner was wont to install his mistresses.

That’s my personal reminiscence of Clark Blaise. Other people know him much better than I ever did, and the intensity of the relationship gradually diminished as he and Bharati moved and moved again to headier and headier jobs. Such is life. One bit of correspondence stands out. I must have complained to him in a letter about some review or other when my first book came out. In the return mail, he sent me a photocopy of his latest royalty check (minus 15% agent fee). The check was for $1.87. On the back he had written, “Welcome to the abattoir of critical reception.” Many lessons there.

At any event, I always admired Clark’s writing, and since Biblioasis had just published his selected stories This Time, That Place with a laudatory introduction by Margaret Atwood, I thought it an opportune moment to dig into one of his stories and map out for myself the powerful underpinnings of his art. It’s always been true of me that I never really get to know a writer until I have written an essay about the work.

As I say, this is just a taste. Order a copy of the magazine, and read the rest: CNQ Issue 113: Spring/Summer 2023.

Close Readings: On “A North American Education”

Reading a story is always an adventure. You think it's going one way, and, lo, it diverges, pirouettes, flips on its axis, and leads you somewhere else. This invariably happens on re-reading; the more re-reading you do, the more complex and dense with meaning a story becomes. This is only natural. A story is unknown country. The first go-through you are feeling your way, looking for landmarks you can identify, noting oddities to be revisited, just sorting out the narrative lines. As you read, you project your protean version of the story in your imagination, a provisional coherent summary, so to speak, making alterations on the fly.

The first time I read Clark Blaise's early story "A North American Education" is lost to the decades, so I came to it fresh, without pre-conceptions. The first go-through I caught the irony in the title. Or thought I had. Books and reading take a beating in this story. More than anything else, what the boy protagonist, Frankie Thibidault, learns about is sex. When he turns thirteen, Frankie's mother starts leaving the usual unhelpful books in the bathroom. His brutally pragmatic father takes him to see a country fair side show stripper after which the little boy ejaculates in his pants without in the least understanding what is happening to him.

He attempts to educate himself by shoplifting porn magazines and spying on the neighbourhood wives seductively hiking up their halter tops in the street, then by plotting to peep on a woman named Annette in the next-door apartment bathroom. This leads not to anatomical revelation but to the awkward discovery that his father and Annette are having a clandestine affair.

Yet I was wrong. Sex lights up the dramatically seedy surface of the story, but the deeper currents are literary and darkly emotional. We return to the title—"A North American Education". The story is constructed in six sections divided by line breaks. The presentation is anachronic, the events told out of order. The long first section relates the life of Frankie's grandfather, born in France in 1832, buried in Quebec in 1912, a man "who had seen two child brides through menopause." The fourth paragraph is singular, anomalous. The first-person storyteller, Frankie grown up, interrupts his narrative to imagine his grandfather in a scene in Gustave Flaubert's 1869 novel Sentimental Education.

I think of Flaubert's Sentimental Education and the porters who littered the decks of the Ville-de-Montereau on the morning of September 15, 1840, when young Frédéric Moreau was about to sail. My grandfather was already eight in 1840, a good age for cabin boys.

This literary reference is an erratic, a boulder out of place in the story, one of those bits of text one races over on first reading, filing it away for further reflection. Blaise is obviously telling the reader where he got his title. More than that, he is tipping his hand as to the story's deeper concerns. "Sentimental" is one of those words that has changed meaning in modern times. Now we think of sentimentality as mawkish, supercharged with exaggerated and false emotion; in Flaubert's day, it meant, simply, feelings, without the negative connotation. Sentimental Education is a novel about Frédéric Moreau's education in feeling through his grand passion for another man's wife.

A new reading of "A North American Education" turns up multiple instances of Frankie's sad indoctrination in affairs of the heart, not just sexual mechanics, but the little boy's entire orientation to the feminine and his own physical being. Step by step, his French-Canadian furniture salesman father teaches him shame, the objectification of women, and the male arts of infidelity, betrayal, and complicity. "Thibidault et fils." Father and son are ineluctably knotted together in their allegiance to a dysfunctional and crippling masculinity, encapsulated in the aftermath of that awful scene at the Kentucky county fair.

Sex, despite my dreams of something better, something nobler, still smells of the circus tent, of something raw and murderous. Other kinds of sex, the adjusted, contented, fulfilling sex of school and manual, seems insubstantial, willfully ignorant of the depths.

On first reading, that description of the grandfather, "the man who had seen two child brides through menopause," astonishingly callus and repellent, had also stood out, the antithesis of romantic, oddly unmotivated in the text. But on this new reading, it begins to cohere within a pattern of patriarchal dismissiveness, the reduction of women to objects, the fatal alienation of male and female, and self-hatred.

This is most obvious in the curious way Frankie's mother is written out of the story, not entirely, but effectively. Mildred has a tiny role, mostly as a foil to the rude energy of Jean-Louis Thibidault. She's a reader, as is Frankie, but Jean-Louis despises books and book learning. The aftermath of the country fair ejaculation scene cycles through a shaming text ("Don't tell me someone didn't see you..."), then a bit about Jean-Louis's educational philosophy culminating in a tirade against reading. Note the author's emphasis on the words "show" and "read" and "know".

"It was supposed to show you what it's like, about women, I mean. It's better than any drawing, isn't it? You want books all the time? You want to read about it, or do you want to see it? At least now you know, so go ahead and read."

The scene ends with Jean-Louis instructing Frankie to lie to his mother. "Tell your mother we were fishing today, okay? And that—that was a Coke you spilled, all right." The lie reverberates at the end of the peeping Tom sequence, when Frankie discovers his father's sexual infidelity and keeps the secret, having learned the virtue of male complicity and the bar of silence against women.

For some reason, perhaps the shame of my complicity, I never asked my father why he had come home, or why Annette had been in our bathroom. I didn't have to—I'd gotten a glimpse of Annette, which was all I could handle anyway. I didn't understand the rest. Thibidault et fils, fishing again.

The irony, of course, is that they are not fishing. By repeating the word in a sequence of contexts, Blaise has rendered it compositional and thematic. It comes to connote the entire realm of toxic masculinity, the shame and secrecy surrounding sex, the voyeuristic obsession with women, the hostility towards femininity.

To read the rest you can order the magazine here: CNQ Issue 113:

Spring/Summer 2023

Interesting. I remember reading that story lo so many years ago.