Eldon & Shannon

Eldon Teflon, the sheep rancher, won his wife Shannon in a card game, and she went along with it mainly because her then husband Wade Marsh was not what she'd expected when they got married on impulse in Tonopah, Nevada, after they met in the all night diner where she worked and he showed her a fan of bills he had scored robbing a medical marijuana dispensary in Boulder the day before. As it turned out, the medical marijuana dispensary robbery was the peak of Wade's trajectory in the armed felony business. He was only eighteen, and things went mainly downhill after that. He had lost Shannon five times in card games before Eldon Teflon showed up and she decided enough was enough. I should add that this was in 2015 and betting your wife in a card game was at that time a highly unusual exercise of your conjugal rights, but Shannon and Wade were largely ignorant of the popular social currents of their age.

Commentary

I dunno. I have a thing for names that sound suggestive or have an eccentric rhythm. I have mentioned this before. They sound good to me, and thus fit seamlessly into a story as it unscrolls from my head. They create ambience, what I call aesthetic space.

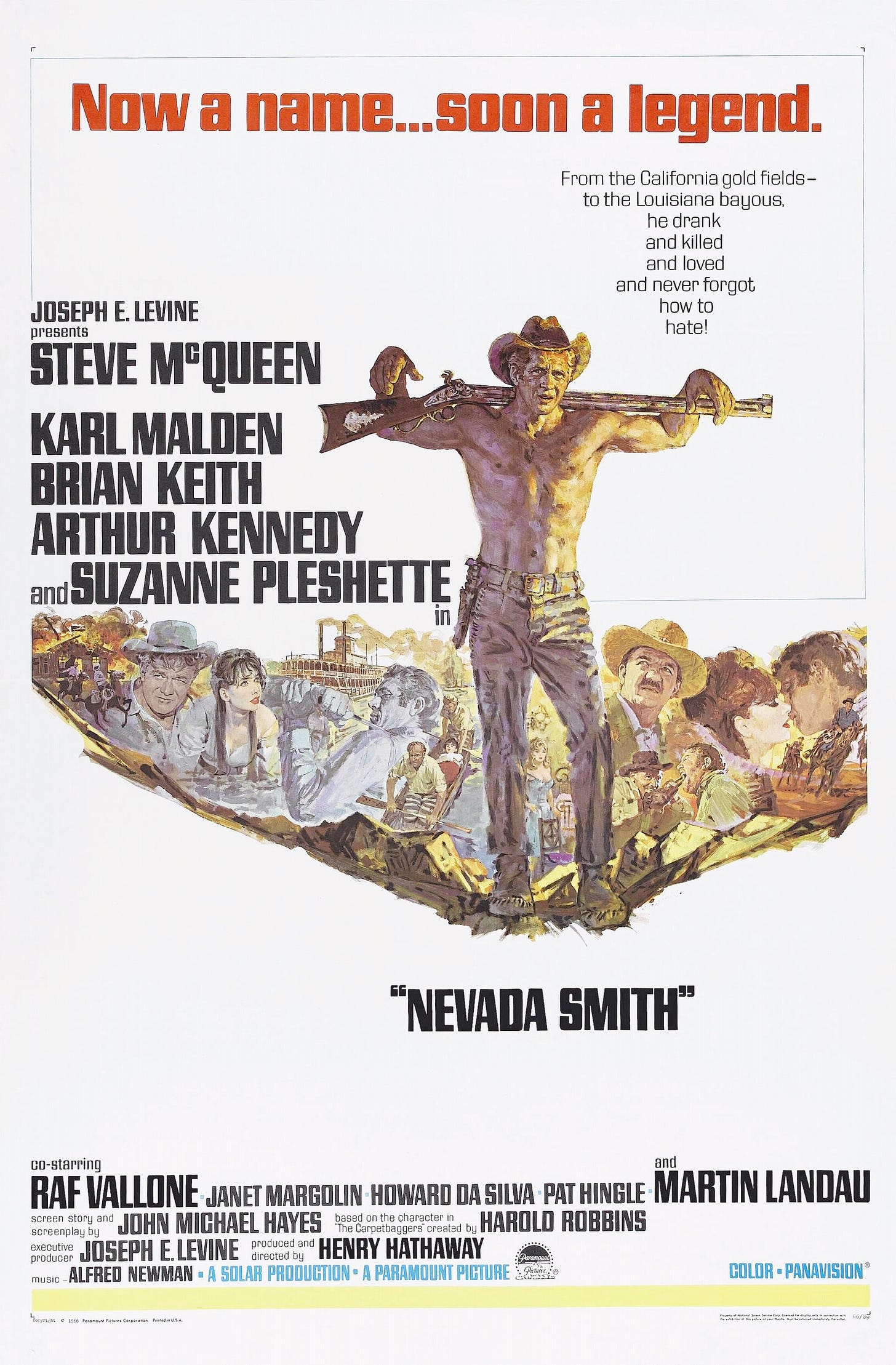

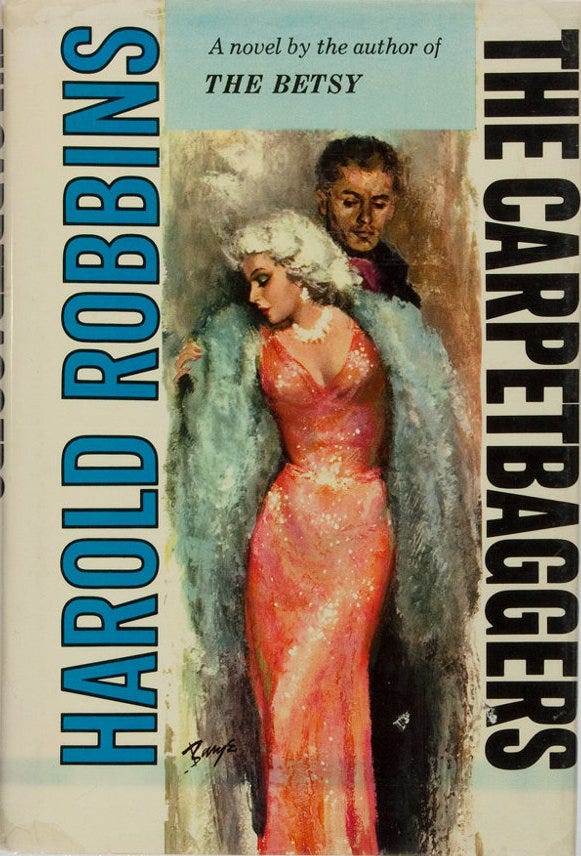

Tonopah, Nevada, is a real place and also a place in my imagination. I like the whole name—“Tonopah, Nevada”—two words of three syllables. I have no idea how Tonopah is really pronounced and I don’t care what the place is really like (I could have looked it up). And Nevada itself is just plain suggestive. I think this has something to do with a character named Nevada Smith in a Harold Robbins novel The Carpetbaggers, which was big when I was a teenager and which I bought from a carousel in a cornerstore on the beach at Turkey Point one summer. The Carpetbaggers was made into a movie and then a sequel called Nevada Smith came out in 1966 just when I was at an impressionable age. Steve McQueen played Nevada Smith. I can still recall pretty vividly a couple of the sex scenes from the novel. Such are the literary antecedents of this story. (While all my illustrious colleagues were reading Proust and George Eliot when they were thirteen, I was reading Harold Robbins—I don’t know what this says about me.)

Tonopah, Nevada came in earlier in my writing career in a story called “Heartsick” about an 89-year-old nymphomaniac in an old folks home in Austria, who once owned a brothel in Tonopah called the Everready. This is just a throwaway in the story but somehow the key to everything that follows. “Heartsick” was first published in The Iowa Review and then in my story collection Dog Attempts to Drown Man in Saskatoon.

I am fairly certain Nevada is a lovely, god-fearing, civilized state and nothing like the hair-raisingly chaotic country of my imagination. So I do apologize for that.

Eldon and Shannon are a rhyming pair. Eldon has an awkward flavour I like, but I couple it with the named Teflon. Eldon Teflon. Teflon is just one of my favourite words ever. I have a bank of names with Teflon as a surname or given name. Nothing sticks to Teflon, neither sin nor idea. Eldon, the name, is awkwardly old-fashioned and conventional; but Eldon Teflon is an empty skillet. And a sheep rancher. Once again, I have nothing against real shepherds. But I have negative associations with sheep that I then attach with anyone dealing with sheep on a regular basis.

I don’t want to digress too much, but I recall doing long distance running workouts in the Pentland Hills outside of Edinburgh when we would come upon sheep that had fallen on their backs and could not figure out how to get upright again (this necessitated having to go look for the farmer). Once in a dense fog I was driving through Holyrood Park in Edinburgh, inching along, only to suddenly discover a flock of the park sheep congregating suicidally on the ring road (as sheep will).

That’s enough about sheep.

Wade Marsh is obvious, right? But he is the main character in the story, the chaotic force driving what plot there is. The betting his wife in card games motif, of course, comes by osmosis and imaginative transformation from Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge, the half-remembered scene where Michael Henchard auctions off his wife and daughter. He is 21 and drunk and a “hay-trusser.”

I might go on about hay-trussing, but I won’t—suffice it to say I grew up on a farm and was once ultra-familiar with hay and straw, though we had machines to do the trussing.

Shannon, Wade’s wife, is the sharpest tack in the story, the one who eventually breaks the mechanical repetition of Wade’s gambling habit by changing the meaning of his lost bet. Before, when he lost her, she seems somehow to have returned, the marriage remaining intact. But finally she chooses to take the game seriously and trades up for a husband with a fortune in wool.

One technical thing to notice: I have a standard rule-of-thumb regarding stories about dissolving relationships. Marriages sometimes go south, for one reason or another, and the couples end up disliking one another. But to portray just that moment, the moment of hatred, is to lie about the relationship. You have to do justice to the lives of these people by portraying the entire scope and story of their marriage. They were in love once, thought well of one another, wanted to spend every waking moment in each other’s arms, etc. So in a very brief space (it’s a microstory, right?), I had tell you how Eldon and Shannon got together in the first place. It’s not romantic, but there he was preening with success, a fan of bills in his hand, eighteen and with all his life of crime before him—that’s the man Shannon fell in love with. And now you know the whole story.

Love this, both the story and the exegesis. Brevity--and suggesting a far larger story within a few sentences--is always a challenge for me. Funny, though: I dropped a wins-his-wife-in-a-card-game tale into an essay in TriQuarterly once, though not nearly as economically told as yours. Nonfiction piece--a cop ex-con in Russia's Far North, whom we hired as a bodyguard in a reporting trip to a gulag-era gold mine, claimed he'd hit the jackpot in a night of gambling.

Love the microstory form you carry off so well. Your approach reminds me of some choice haiku advice a friend recently conveyed from Cor van den Heuvel, taking the already condensed form a step further (or back): "Write 1/2 the poem."