Hetty Among the Indians, or the Making of a Native American Poet

How my half-Hopi cousin came to be and nearly won a Pulitzer Prize

It may come as a surprise to you all, but the Native American poet Wendy Rose is a cousin of mine. Apparently, writing flows in the blood.

Wendy Rose is the pen name of Bronwen Edwards, a Californian, one-half Hopi and about an eighth Miwok. She has published an armload of books, including Lost Copper (1980) which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. We share a great-great-great-grandfather who was born in Scotland in 1809 and emigrated to Canada in 1836. Hetty was his eldest daughter, Bronwen’s great-great-grandmother. Hetty’s story, leading down to Bronwen, is as exciting as any Hollywood epic, touching on the Gold Rush of 1849, Native American genocide, saloon gunfights, wagon trains under attack, and those Native American lovers. Thus she is a hybrid soul, both settler and native, colonizer and colonized. Bronwen has written her own book about the family, Itch Like Crazy.

But here is my version. It’s an out-take from an early draft of the book I am working on. Unfortunately, lots of dates, but that’s the nature of the beast.

I hasten to add, since people do get confused and jump to conclusions, that I make no claim to Native American blood for myself. This is completely on Bronwen’s side of the family, descended from Hetty. I was not so lucky.

"I have not been Making my Pile as fast as I thought I should when I left home." — Joseph Barrett, Henrietta's husband, from the gold fields of California, 1868

1. First Years

On March 16, 1831, my great-great-great-grandfather Andrew McInnes (1809-1891) married Sarah Clark (1814-1891) in Fort Augustus at the foot of Loch Ness. Sarah was the daughter a prosperous tacksman, Thomas Clark, and his wife Ann McKay. Thomas Clark held the lease (from the Fraser of Lovat) on a farm called Auchterawe on the wooded hillside above the River Oich just south of the town near an ancient iron age hill fort. Sarah was born at Auchterawe on July 8, 1814, the youngest of seven brothers and sisters. It was said she was a great rider, with a blood horse of her own.

For the next few years she and Andrew lived in various places in the Great Glen finally settling in Bunoich a suburb of Fort Augustus. Their first child Henrietta Rudyerd Clark McInnes was born in Fort Augustus on February 27, 1832. The birth record indicates that at the time Andrew was living at a house called Caruanaw in Killmallie just outside Fort William.

By 1836 Andrew was in Canada looking for a place to bring his family, and in early 1838 Sarah sailed to Canada with their three daughters, Henrietta, Ann, and Isabella. The family settled in a frame house at the centre of Vittoria, Norfolk County, Upper Canada, near the north shore of Lake Erie, in an area where most of the early settlers were United Empire Loyalists from the United States. In 1849 the family moved to a frame cottage about a mile west of the village, which they named Aberfoyle after the Scottish village where Andrew was born.

In 1849, at the age of 17, the eldest daughter Henrietta married a boy named Richard Rapelje, third son of a Colonel Rapelje, a Loyalist from New Jersey who led a band of "Incorporates" at the Battle of Lundy's Lane in the War of 1812 and became Sheriff of the London District. According to the Hamilton Spectator, the wedding took place at Aberfoyle on November 14, 1849. In December 1850 they had a son named Abraham who only lived for a day. In September 1852, Henrietta bore a daughter named Sarah Willimina, who died the following April. But Sarah Willimina only barely outlived her father who succumbed a month after she was born at the age of 19.

In 1856 Henrietta married an Irish immigrant named Joseph Barrett and together they decamped for the gold fields of California where they established an American branch of the family. Joseph Barrett was born in Tipperary, the son of a Hugh Massy Barrett who sometime after Joseph's birth brought the family to Canada. Hugh died in Port Rowan at the foot of Long Point on Lake Erie in 1868. Henrietta and Joseph Barrett had seven children: Florence Henrietta (1857), Mary Elizabeth "Lizzie" (1859), George (1862), Hugh Massey (1864), Caroline (1866), Isabella (1869) and Harry Joseph (1871).

Henrietta only returned to Vittoria once, in 1905 after her husband's death. On that occasion she recalled the day they left Aberfoyle for good and the sight of her thirteen-year-old brother Walter McInnes sitting on the fence in front of the house, idly dangling his legs as he watched her go. This image is a poignant metonym for all deaths, removes, losses, distances, and solitudes of Hetty’s life.

2. Present at the Slaughter

A Barrett family story related by Hetty's descendant Bronwen Edwards has it that Joseph Barrett sailed to California in 1849 at the start of the gold rush. He made good, panning $60,000 worth of nuggets, and returned to Vittoria a rich man, like the young men in fairy tales. With his new wife and his fortune, Barrett returned to California, sailing from Nova Scotia and crossing the Isthmus of Panama. Their first child, Florence, was born in San Francisco on August 30, 1857, on that trip. Barrett never struck gold again, and the remainder of his life was spent burning through that first $60,000.

The couple settled in the gold mining country of western Mariposa County in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, east of San Francisco, northeast of Fresno. In the decades leading up to the gold rush the county had been rarely visited by whites. It was the ancestral home of the the Yosemite and Chowchilla (branches of the Miwok) who naturally resented the sudden influx of tens of thousands of placer miners. The Yosemite made small raids, mostly stealing horses and mules, but the miners retaliated by forming a militia and starting the Mariposa War of 1850-51. Native villages were destroyed, inhabitants slaughtered. The remnants were rounded up and moved to reservations while a few fled east to take refuge with the Paiutes.

Five years later when the Barretts arrived the Yosemite had been pacified, removed and emphatically reduced in numbers. But the killing had not ended. According to Benjamin Madley in his book American Genocide, The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, "Between 1846 and 1870, California’s Native American population plunged from perhaps 150,000 to 30,000. By 1880, census takers recorded just 16,277 California Indians. Diseases, dislocation, and starvation were important causes of these many deaths. However, abduction, de jure and de facto unfree labor, mass death in forced confinement on reservations, homicides, battles, and massacres also took thousands of lives and hindered reproduction."

We tend to think that we only just discovered the repressed history of North American genocide, but as early as 1890, the historian Hubert Howe Bancroft put the matter even more dramatically than Madley. “The savages were in the way; the miners and settlers were arrogant and impatient; there were no missionaries or others present with even the poor pretense of soul-saving or civilizing. It was one of the last human hunts of civilization, and the basest and most brutal of them all.”

The Barretts lived in a series of places that have since become ghost towns — Smith's Ferry, Quartzburg and Merced Falls. Barrett's Ferry, where they stayed long enough to give the place their name, now lies beneath Lake McLure behind the New Exchequer Dam. In a letter from Quartzburg in 1868 Joseph says he likes the climate of California but he and Hetty miss the society of women. He admits, "I have not been Making my Pile as fast as I thought I should when I left home." By 1868 the placer mining that had propelled the initial gold rush of 1849 was already dwindling for lack of gold. For a time it seemed as if the county would revert to wilderness, but then lumbering revived the area through the 1920s, after which it too faded away, and the mills closed down.

Barrett set up a store and local banking service for miners on the Merced River. In the 1870s he bought a ranch at Merced Falls in partnership with a man named James Pillans. The family didn't move to the ranch until the late 1870s. That's where they lived until Joseph's gruesome death in 1904. A report in the April 9, 1804, Mariposa Gazette reads: "Joseph Barrett died at his home at Merced Falls on Monday at the age of 82 years. During the previous two weeks his health had failed rapidly, and on last Sunday evening he received some burns which probably hastened the end. Mr. Barrett was sitting in front of the fire place, being alone in the room at the time, and fell in the fire. His wife was attracted by his calls and found his clothes on fire. The fire was put out at once, but he had received some severe burns."

I found a passing reference to Henrietta in a book called The Ahwahneechees: A Story of the Yosemite Indians (1966) by John W. Bingaman. He tells the story of an native girl named Phoebe Hogan, born in 1886 in Merced Falls. At the age of ten (so 1896) she left school and started working for Henrietta Barrett at the ranch as a dishwasher and housekeeper. According to Bingaman, the Barretts "ran a resort and stopping place for stages and freight wagons."

A year later 1905 Henrietta made the cross-continental journey by train to visit Vittoria 48 years after leaving. She brought with her one of her daughters, Lizzie Newman, and Lizzie's son Joseph. Her parents and five of her sisters had died in the intervening years. Aberfoyle was still in the family, though I am not sure who was living there. Her youngest sister, Georgina Dawson, lived in the farmhouse across the road, and another sister, Sarah McCall, wife of Senator Alexander McCall, was living in Simcoe, the county seat. Her two doctor brothers, Walter and Andrew also were still alive, but I think Andrew was mostly farming at the time. He was a world traveler and a man who put on airs. He liked to call himself Andres. There were plenty of in-laws, nieces and nephews to visit in Port Rowan, St. Williams and Port Dover. A highlight of the trip was a picnic organized by Georgina at Fisher's Glen on the lake.

In 1912, Henrietta's brother Dr. Andrew, his wife Annie, and a niece named Edith McInnes, his brother Walter's daughter, took the train journey in reverse, arriving in California in late December, having spent Christmas in Salt Lake City. Henrietta was living at 2624 Grove Street in Berkeley with her daughter Lizzie Newman, also a widow, who rented rooms in her house to boarders.

Annie McInnes wrote a letter home dated December 28, shortly after their arrival. She and Edith were staying in a hotel, while Andrew had gone to the Barrett ranch at Merced Falls to hunt quail (he had brought a gun and hunting clothes from St. Williams for this purpose). Annie says that Hetty was unwell and lying down when they arrived, though animated when she talked. Annie says she is thinner and more lined than when she visited Vittoria in 1905. Annie describes the range of hills she can see from the house, the roses, geraniums and calla lilies in blossom in the yard, though to her eyes they have "a dusty rather dried look." Maiden Hair and morning glory climb the verandas.

Henrietta died on September 7, 1915. As reported in the ever helpful September 11 Mariposa Gazette, "Mrs. Joseph Barrett died at the home of her daughter, Mrs. M. E. Newman [Lizzie], in Berkeley, on Thursday morning of last week at the advanced age of 83 years. She was a native of Scotland but had spent most of her life in America having come here when a girl. She was a pioneer of Mariposa county having lived at Barrett's, on the Merced River in early days and afterward moved to Merced Falls."

3. Shootout at the Bon Ton Saloon

Except for one particular line that leads from Henrietta's daughter Mary Elizabeth "Lizzie" down to my California cousin, Bronwen Edwards, the Barretts tended to fade into the genealogical ether. The first born Florence Barrett (1857-1952) married Samuel Butler. In 1904 they were living in a place called Fresno Flats. Lizzie Barrett married Maurice Newman in 1885, and I will tell her story in more detail hereafter. George Barrett never married. Rootsweb has him listed as a stockraiser. Hugh Massey "Hugo" Barrett married a woman known variously Alice E. or Emma Alice. According to his death announcement in the Mariposa Gazette, he died in his own bed November 4, 1916, at 4:30 in the morning of heart failure. He was a farmer and lived in the vicinity of Merced Falls and perhaps helped manage the Barrett ranch.

Harry Joseph Barrett married Anna Luisa Bruschi in 1897 in what the Mariposa Gazette called "the most brilliant wedding ever to take place in Coulterville." But two years later Anna suffered an unnamed illness that affected her mind, and she was committed to the Stockton State Hospital where she died at the beginning of September, 1905. Rootsweb has Harry listed as a grocery merchant.

As already mentioned Mary Elizabeth "Lizzie" Barrett married a man named Maurice Newman (1860-1903) in 1885. There is a family legend about Newman, which I learned from Bronwen and then added to myself with my own research. Newman was the son of a woman named Margaret Bigler. The Biglers, Joseph (originally Bürkbüchler or Buerkbuechler) and Margaret Kestor, were German immigrants, married in Missouri. In 1854 they made the arduous overland journey to the gold fields of California. This was by wagon train, not railroad. One of their daughters wrote a letter describing the journey. It reads like a cross between a James Fennimore Cooper novel and a Hollywood Western.

"The Indians were plentiful but never annoyed our party except one time when they drove a herd of buffalo among our cattle and caused them to stampede. We had quite a time getting the cattle together again. One buffalo was pierced with a great number of arrows. The animal would run until exhausted from loss of blood then the Indians would cut its throat. The Indians massacred people in front of our party and behind us, but we always treated them kindly. They were very anxious to get bread so we gave them a small piece of bread for a pair of moccasins and they would be delighted. One day the Indians were dancing around a tree and having a great pow wow and upon in inquiring. We were told they were burning up a man."

This was only the beginning of their misadventures which included fighting off bears, losing half their cattle to bad water at the Great Salt Lake, and having to jettison their baggage for lack of oxen to pull their wagons. The last leg of the journey was accomplished in a drought, and when they arrived at the gold fields there wasn't water to wash for gold.

"From Salt Lake we crossed the Sierra Nevada mountains and finally reached Hang Town. The party separated there selling wagons horses and what few head of cattle we had. Our family and Uncle Castors' went directly to Mariposa County and still there was no rain and it was nearly four years before there was a good winter rain. There was plenty of gold in the ground but no water to wash it in the rockers. There was a very small stream of water running down a creek and people dammed it up and people used it to wash a few pans of dirt in the rockers. Every day Mother had to go to the dam very early every morning to get a little water before the men came to do the gold washing in the rockers. The pioneers certainly had hard times."

Maurice Newman was born in Bear Valley, California, to Margaret Bigler in 1858 or 1860. She is reputed to have been the first white woman in Bear Valley and owned a saloon called the Bon Ton. Her husband Joseph Bigler who was shot to death in 1857 trying to break up a tavern brawl. Subsequently, she took up with an unnamed Miwok man and became pregnant. Fortuitously, she met Maurice Newman, a Prussian sailor who had had landed in California in 1853. In 1857 he made his way to Bear Valley just in time to watch the unfolding drama of Margaret Castor-Bigler's life. He gallantly stepped in to rescue her from an embarrassing situation. He married her, taking the half-Miwok child as his own and giving him his name Maurice Newman.

There is a whole chapter on the Newman-Bigler courtship in Newell D. Chamberlain's 1936 book The Call of Gold, although he doesn't mention the Miwok lover. But Bronwen, writing under her nom de plume as Wendy Rose, tells the whole story in her book Itch Like Crazy. She concludes somewhat wistfully, "I wish that I knew more about the Miwok man that Margaret had known; Miwok people today in the Mariposa area tell me that they have heard stories about the Newmans."

The Mariposa Gazette (June 15, 1895) eulogized the original Maurice as follows: "Last Saturday morning as our towns people awoke, they were shocked beyond measure to hear that our county clerk, Maurice Newman, had died very suddenly at daylight. The news seemed almost incredible, but that it was true was shown by the sad faces on every hand.

"Mr. Newman's health had been failing for some time, but he was ever at his post, most of the time doing the work of three men, and especially during the last month he had overworked himself. All during the term of court he had been under a severe strain, but every day found him zealously performing his allotted tasks.

"On Friday night of last week, when we saw him going home at the close of the long day, we little thought that when the sun rose its light would rest upon his folded hands, or that the cheerful morning sounds would fall on unheeding ears. He had rested easily through the night, but a little after 4 o'clock he awoke his wife and complained of a severe pain about his heart. He arose and walked around a few minutes, but finding no relief, allowed Mrs. Newman to send a neighbor after a physician. She then ran assistance, but by the time she again reached his side he was breathing his last."

4. The Coming of Wendy Rose, Miwok/Hopi Poet

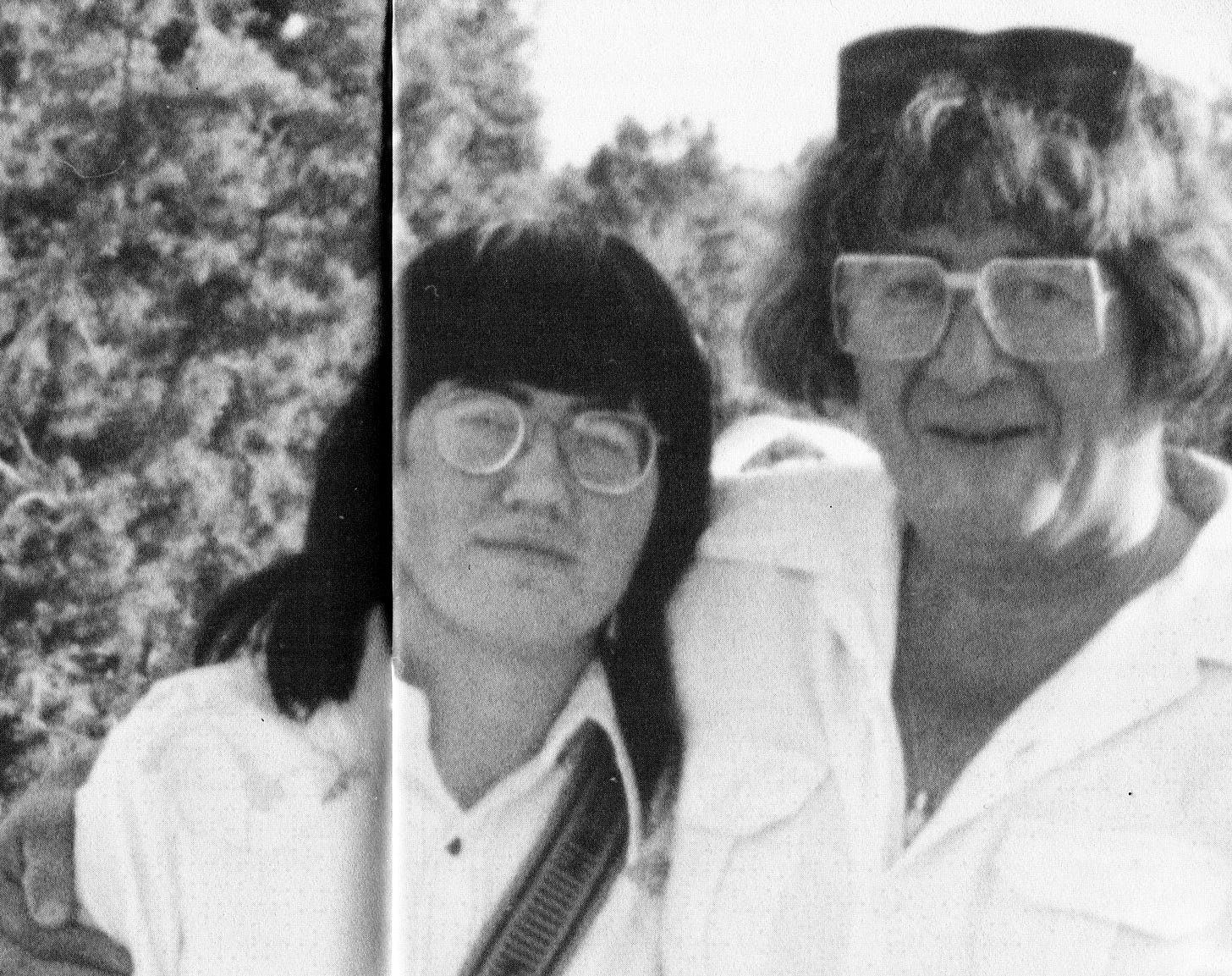

Thus the Maurice Newman who married Lizzie Barrett was half-Miwok. He and Lizzie had three children: Maurice (1886), Claire (1888) and Joseph Barrett (1890). In 1911, their daughter, Claire, married an English photographer named Sidney Valdez Webb. The Webbs had three children: Elizabeth "Betty" Claire (1912), Dorothy Emily (1914) and Sidney Joseph (1915). In the late 1940s, Elizabeth, like her great-grandmother Margaret Bigler, had an affair with a Native American, a young Hopi artist from Arizona named Charles Loloma (1921-1991). Bronwen was their daughter. Elizabeth subsequently married a man named Edwards, and Bronwen took his last name. Later she adopted the pen name Wendy Rose under which she has accumulated a substantial publication history as a Hopi/Miwok writer. Her 1980 book Lost Copper was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry.

Her biography at the Poetry Foundation web site reads in part: "The daughter of a Hopi father, Rose grew up feeling distanced from both Hopi and white society. She spent a troubled adolescence before attending college and eventually earning her PhD in anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley. As a Native American, she has claimed to have often felt like a spy in the field of anthropology."

Wendy Rose's book Itch Like Crazy is a collection of poems and essays, family history and genealogy. It contains two bitter poems about our mutual 3x-great-grandfather, Andrew McInnes, which she spells MacInnes (the family goes back and forth the spelling). From internal evidence she seems convinced of the untrue family story that he was a young planter and slave owner in the West Indies. She also interprets his commissions in the Norfolk Militia as evidence that he was an Indian fighter, when there were no wars in Ontario between the indigenous residents and whites after the War of 1812 (and even in that war, the First Nations mostly fought on the Canadian side).

In her poem "Andrew MacInnes, You Look West Just at the Moment I Look East," she writes:

Your children will dance the bygones of you

for you rattle your veins like distant thunder

without the promise of rain. You are not quite a memory

nor are you a myth,

nor are you the clear cool brook

over rotting sycamore leaves,

or the blood that swirls

and mingles with fish.

Condor will teach them if you will not;

your grandchildren's grandchildren will know

how to crouch and howl like trapped wolves

so loud you will hear them beyond the grave.

They will pound their fists in the ground

and you will think you hear a million buffalo

running over the land. Your children, Andrew,

will go native, they will dance

to the rise and fall of summer,

surround winter's lodge

with their crackling song.

Well, I just read that Taylor Swift is also related to the White Nun of Amherst. Trump has made us realize that he is more popular tha Taylor, but maybe your combined genealogies will put you near enough to se his ample coattails!

Whew! That's a tangled family tree.