How Samuel Baker met his wife

I’ve been lost in reading — this time a gem called In the Heart of Africa by Samuel White Baker first published in the 1880s but describing his explorations in Egypt, Sudan, and Uganda in search of the source of the Nile River in 1861-64. Actually, the English explorers Speke and Grant had already discovered the source of the Nile (Baker ran into them on their way home), but they had skipped Lake Albert, and Baker cheerfully went off to fill in the missing bits on the map while annihilating as much of the local wildlife as he could manage. For this he received a knighthood.

Thus far, he seems like any other imperial explorer of his era, a white man with money and a gun, pretending that all the local inhabitants had no idea where they were living until he found them.

If you read the book the way Baker intended it to be read, it’s pompous and a bore, reeking of racial superiority, testosterone, condescension, blood, and slaughtered beauty (he calls one of his guns “baby,” but he will go on at length about the beauty of the animals he has just shot to death, some of which are now nearly extinct). But, of course, this isn’t the way to read the book.

When reading any historical document, you have to triangulate. First, you must set your contemporary point of view, biases, and scruples to one side (without losing sight of them). Then you have to analyze the author’s point of view, biases, and scruples, using the document to come at some sense of who the author was, what he thought he was doing, and the culture-world that made him. And finally, having bracketed all this subjectivity (always a good exercise), you try to see what is fresh and interesting in the document, usually something the author did not intend to reveal, something off-center, in the wings, or just out of focus.

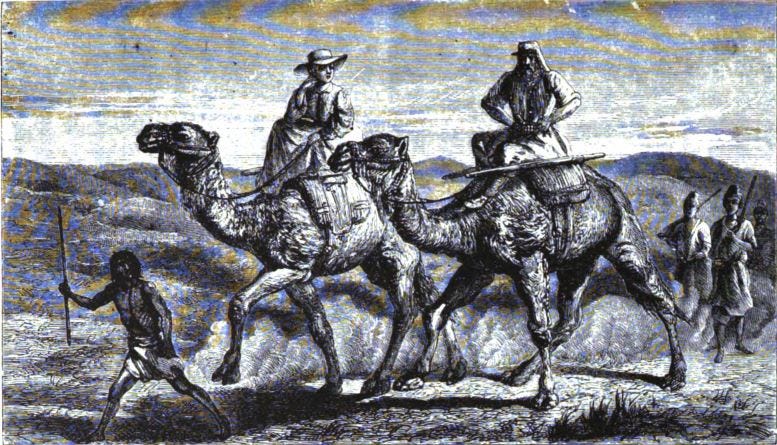

For me, the first astonishing thing about In the Heart of Africa is that Baker brought his wife with him (actually, it sounds as though she simply refused to stay home), and though he often seems to mention her only in passing, it gradually becomes clear that she was a remarkably brave, intelligent, feisty, and loyal woman. African exploration by Europeans was a men’s club activity. Florence Baker’s presence on the expedition amazes and delights. Not only that, but she saved Baker’s project (and possibly his life) multiple times. On one occasion in particular, she intervened when Baker’s Arab staff (porters, guards, camel and donkey drivers) mutineed and threatened to shoot him.

I did not wait for the arrival of my men, but mounting our horses, my wife and I rode down the hillside with lighter spirits than we had enjoyed for some time past. I gave her the entire credit of the "ruse." Had I been alone I should have been too proud to have sought the friendship of the sullen trader, and the moment on which success depended would leave been lost.

To read this aspect of the book properly you have to do a little research. Then the full marvel of the thing begins to blossom. Mrs. Baker, later Lady Baker (after that knighthood), was a Hungarian woman, Florence Barbara Szazs, notably blonde, blue-eyed, and handsome (in all her pictures she looks calm and resolute). She was born in Transylvania in 1841, then orphaned at the age of eight in 1849 when Romanian raiders massacred her family. She ended up a slave sold to a Turkish official at an auction at a place called Vidin in Bulgaria in 1859. Baker who happened to be in town on a hunting expedition (basically, what he did most of his life) caught sight of her, fell for her, and helped her escape (or he bought her, the stories vary). She was 18, he was a 37-year-old widower with considerable inherited wealth, educated as an engineer (he built bridges and invented a hunting rifle with two barrels). After meeting in Vidin, they seem never to have parted.

As I write this, I am hoping you are as surprised as I was at this astonishingly dramatic story, not just because of the Hollywood romance aspect. We are so used to the history of slavery in the American South and the evils of the Atlantic slave trade. And we know that serfdom in eastern Europe and Russia was similar in certain ways to chattel slavery. But it’s still a shock to realize that slavery was practiced on the Turkish marches of Europe long after Britain had outlawed it (1834). Also that it was not race-based slavery, at least not race-based in the way we have come to understand it. Orphan Florence Szasz was bound for a harem when Baker first saw her.

In his book, Baker doesn’t mention anything about his wife’s past. But rumors spread ahead of them. Even after Sir Samuel Baker was knighted, Queen Victoria refused to allow Florence Baker to appear in court, suspecting that they may have slept together before marriage. Tsk, tsk.

Of slaves and slave-trading

Florence’s stint as a slave in Bulgaria segues naturally into Baker’s brutal descriptions of the slavery and slave-hunting in Sudan and what is now Uganda in In the Heart of Africa. At the time of his journey, Sudan was ruled by Egypt.

Upon existing conditions the Soudan is worthless, having neither natural capabilities nor political importance; but there is, nevertheless, a reason that first prompted its occupation by the Egyptians, and that is, THE SOUDAN SUPPLIES SLAVES.

Once again, the American (and British) history with slavery tends to mask from us the ancient spread of slavery in other directions. Long before the Portuguese invented the Atlantic slave trade, Arab slave traders had been shuffling Africans across the Sahara and down the Nile to Egypt. Baker and his wife saw how this worked during the years they spent in Sudan hunting, exploring, and prepping for their great expedition up the White Nile.

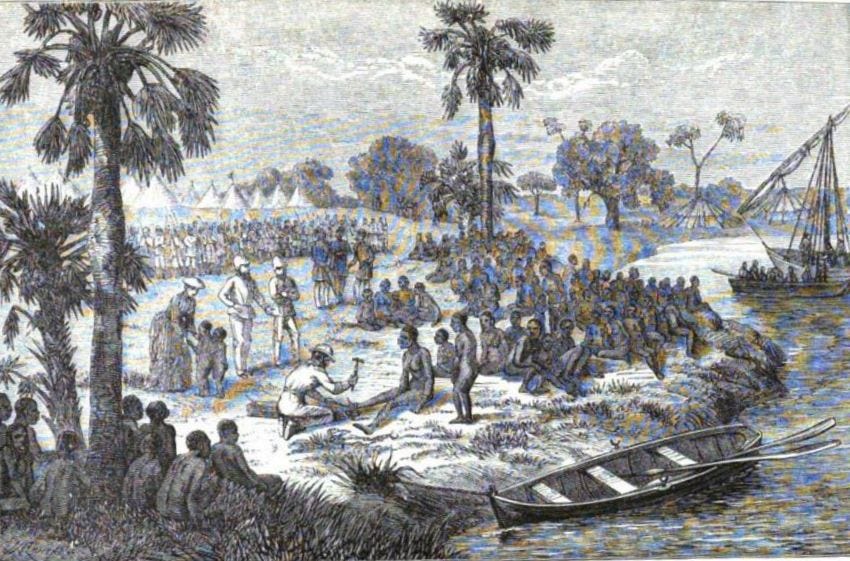

Arab traders, under the guise of dealing in ivory, would mount huge, well-armed expeditions into the Nile hinterlands. These expeditions were financed on credit, payable in ivory on their return. The African villages and small tribal chiefdoms were not armed with modern weapons nor able to form any kind of mutual defense associations. The slave traders would cajole and threaten one village into joining them and together they would surround the target village. They would set fire to the huts, shoot the men as they came out to fight, and round up the women and children to be sold later. The village cattle would go as a bribe to the cooperating villagers. And the traders would dig up the hut floors for valuables and caches of ivory, which they used to repay their creditors. The slaves were pure profit.

Charmed with his new friends, the power of whose weapons he acknowledges, the negro chief does not neglect the opportunity of seeking their alliance to attack a hostile neighbor. Marching throughout the night, guided by their negro hosts, they bivouac within an hour's march of the unsuspecting village doomed to an attack about half an hour before break of day. The time arrives, and, quietly surrounding the village while its occupants are still sleeping, they fire the grass huts in all directions and pour volleys of musketry through the flaming thatch. Panic-stricken, the unfortunate victims rush from their burning dwellings, and the men are shot down like pheasants in a battue, while the women and children, bewildered in the danger and confusion, are kidnapped and secured. The herds of cattle, still within their kraal or "zareeba," are easily disposed of, and are driven off with great rejoicing, as the prize of victory. The women and children are then fastened together, and the former secured in an instrument called a sheba, made of a forked pole, the neck of the prisoner fitting into the fork, and secured by a cross-piece lashed behind, while the wrists, brought together in advance of the body, are tied to the pole. The children are then fastened by their necks with a rope attached to the women, and thus form a living chain…

This is the situation in the early 1860s. The slave trade, with the ivory trade as a front, was in full swing. In fact, the slave traders were so apprehensive that Baker was out to interfere with their business that they plotted to disrupt his expedition, subborned his workers, and even incited them to murder him. (This is where Florence’s advice and brave interventions came in handy.)

Again, to get the full effect of this passage, you have to read beyond the book. Just four years after the explorations described in In the Heart of Africa, Baker and Florence returned to Sudan in 1869 at the behest of the Kedhive of Egypt to lead a military expedition to suppress the Nile slave trade. As far as I can tell, it was only partly successful, but Baker got another book out of it (good lord, he was prolific; Florence helped), Ismaila, A Narrative of the Expedition to Central Africa for the Suppression of the Slave Trade.

Hunting elephants with swords

The 1861 expedition took four years. Baker and his wife were patient. Among other things, they taught themselves Arabic while they were hanging around. But Baker spent much of his time hunting wild animals, Big Game. He pens amazing descriptions of the chase, exciting, bloody, and to many contemporary minds redolent of that rapacious exploitation of what were thought to be infinite resources that still characterizes modern capitalism. Seven elephants in one day! Albeit, the fat was boiled down and packaged to ship back to Khartoum, the hides were dried to make shields, and the ivory harvested.

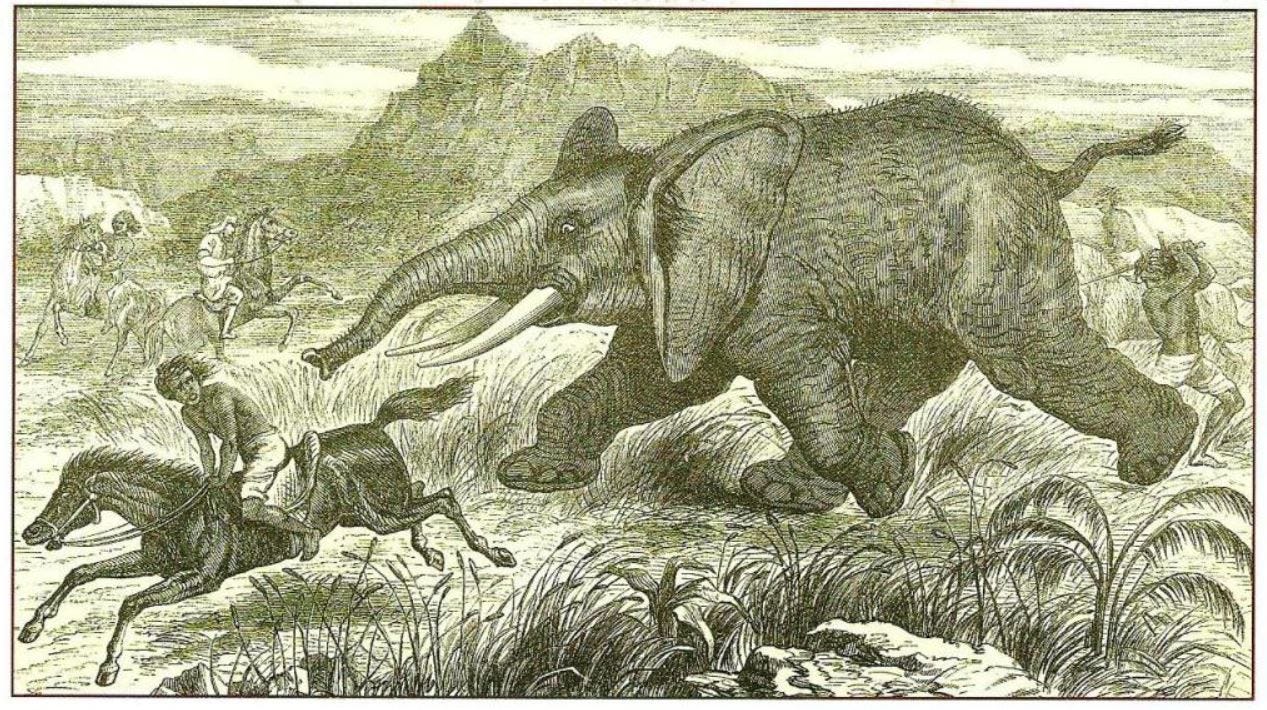

But Baker’s singular attention to local hunting practises is, to me, revelatory, in particular the so-called sword hunters of Hamran. These are men who hunted elephants and rhinos on horse and on foot, not with guns, arrows, or spears, but with swords. I have often wondered how our Ice Age Neanderthal cousins and early homo sapiens hunted the huge, lumbering mammoths and aurochs and cave bears. Baker gives us a clue and a picture.

On one occasion, he hunted elephants with a party of Arabs, close friends and brothers. One had been crippled by an elephant in an earlier hunt. He was small in stature, his left arm shriveled into something like a hook. He would ride a horse with the reins looped over the hook and a sword in his right hand. He was the bait. It was his job to challenge the elephant, taunt and enrage it, then, whirling around, make it chase him. He had to let the elephant follow close enough to stay interested while not allowing himself to be caught. At the same time, his companions would race up behind the elephant, and, dismounting, hack at the animal’s tendons with their swords, dashing out of the way if the animal turned. The result was gruesome. Baker describes an elephant stopped in mid-charge with its feet hanging off its legs like loose boots, suddenly immobilized and helpless. In one case, a sword cut severed a leg artery. Baker offered to shoot the elephant, but the hunters said no, the animal would shortly bleed out painlessly. No need to add to its terror.

This is gruesome for sure, but a glimpse into some ancient way of life, it seems to me, men hunting as a team, someone quick and brave acting as the bait. A strategy, not just a bunch of people standing around poking animals with spears. Tragic, insanely dangerous, with the strange, melancholy beauty of a bull fight.

The Bakers eventually retired to an estate in England. Sir Samuel died in 1893 at the age of 70. Florence died in 1916. Her diary of the expedition to suppress slavery was published in 1972.

Utterly fascinating and informative, Doug! Thanks!

Your explanation of how one should read historical documents like Baker's is right on the mark. Would that more readers (including "scholars") followed your advice.