So I am working on this book, endless, endless.

One part of the project is experimenting with what I can learn about the lives of slaves on Grenada and Carriacou from reading the Slave Registries. This is another way of filling in the landscape of those islands.

The Slave Registries were annual censuses required by the Colonial Office in London from 1817 to 1834 (the first date varies among the West Indian dependencies). You’ll recall that Britain outlawed the Atlantic slave trade in 1807. In 1834, slavery itself was abolished (July 31, to be exact). But between times, the Colonial Office wanted to get a handle on the numbers and treatment of enslaved people as part of a response to anti-slavery politics in Britain. Also, as most people realized the end of slavery was coming and that there would be some form of indemnity paid out to slave owners, the censuses provided a way of pinning down the extent of that payout. The planters used the last censuses to validate their indemnity claims.

A side effect of this data collection was that an amazing amount of information about the enslaved people is now available for anyone persistent enough to scroll through page after page of handwritten lists. For example, not only did they collect brute population data, but annual Increase and Decrease reports recorded births (and mothers’ names) and deaths (with brief medical diagnoses), also sales, rentals, and transfers.

I will tell you that the first time I looked at a page of the Slave Registries, with the planter’s name at the top and then name after name after name of enslaved persons, my heart did drop. I mean it — what I felt — my blood pressure must have dropped from dread and truth. Nothing had ever made the concept of slavery so real to me.

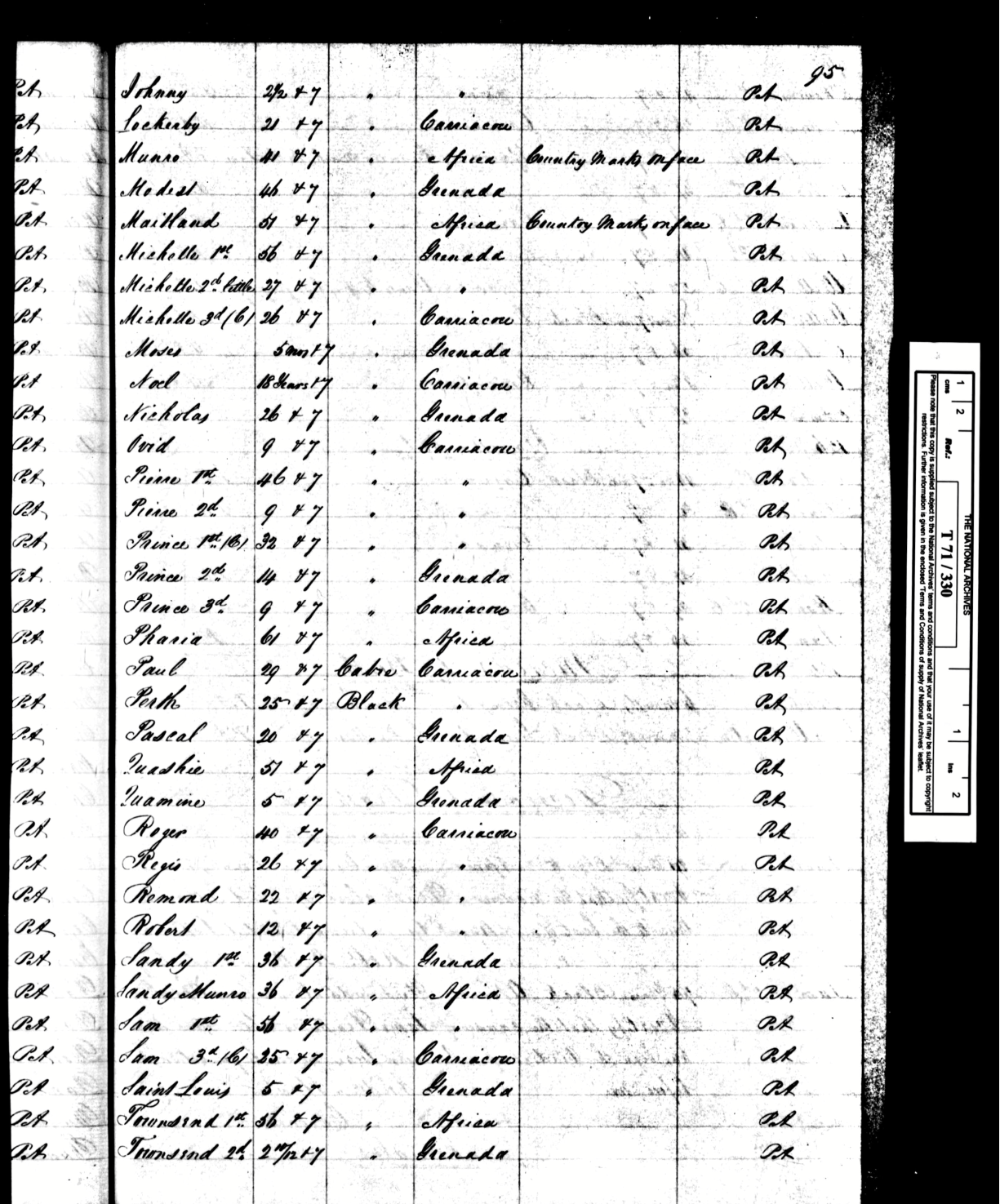

The Slave Registries are actually available to anyone with a computer and a paid Ancestry.com account. They are basically account books, with lined columns — name, age, color (the people were color-coded: black, mulatto, mustee, cabre, mustefino, etc. depending on parentage), place of origin (whether they were born in Africa or one of the islands, hence the phrase “creole of Carriacou” means born on Carriacou), and identifying features (most often “country marks in the face” which was the planter way of indicating ritual scarification, but also “afflicted by sores,” “a leper,” “lame left leg,” etc.). Each page is a separate image file.

A lot of things make using these registries difficult. First, as far as I can tell, they are incomplete. I collected as many as I could for my purposes but still found years missing for particular estates. Thus people would go missing from the record and it wasn’t just because someone forgot about them. The handwriting is very hard to read, clerk’s hand, very flamboyant sometimes and the ink runs and suddenly you don’t know if the name is Soossah, Looshuh, or what. And then the clerk might spell a name differently from one year to the next, or the names might simply morph — Suzy to Susie to Susy to Susie 3rd. And there were a lot of people with very simple names like Bob, Mary, Louisa, and it could be nearly impossible to disentangle them.

I was working on the Marys, as I called them, the other day. In the 1834 Mount Rich report, you get five Marys — Mary 1st, Mary 2nd, Mary 3rd, Mary 4th, and Mary5th. I thought I had tracked two women in particular named Mary, one had two children and the other had three, but I could only find one Mary in 1817 and one Mary in 1834 that fit the chronology. Finally, I decided they must just be the same woman who had a remarkable five babies between 1817 and 1834. At least that was the simplest model. But that was an executive decision of sorts. There were crucial Increase and Decrease reports missing that would have added the missing link.

And there are still at least three Marys I have not fully figured out.

The Registries are indexed and searchable up to a point. This is extremely helpful. You can filter by name (which might, of course, be misspelled), by birth year (if you know it, and, my goodness, those clerks played fast and loose with birth years), and by owner’s name (which might also be misspelled or miscopied). But in the end this only helps narrow things down a bit. I still had to spend hours and hours jumping back and forth between images and search queries, scanning line after line of names.

But over time and laboriously I did manage to evolve some information, life stories almost, for some of the people who lived on Carriacou and Grenada between 1817 and 1834. I had the best success with women who had babies because they showed up by name on the Increase reports. So I can say when Sue, who was 19 in 1817 and living at the cotton, corn, and cattle estate of Anse la Roche on Carriacou, had her first baby. When she was moved to Industry Estate. When she and her babies were sold to Mount Rich on Grenada. And so on. By the color of the child, I can tell if the father was white, black, or mixed race. Occasionally, I could cluster people together as they were sold between estates and make a good guess as to who might be a father. This was rare. Babies died, mothers died, sometimes people were sold or freed. These things were noted down (except, of course, in years when the reports are missing).

Some plantations reported the jobs the various enslaved people performed. I was unlucky in that the plantations I am interested in did not.

Most of the brief lives I discovered were very brief indeed. Brief and sad.

Born at Mount Rich, John Paul is one year old in 1817. Two years later, he dies of marasmus, age three.

Joseph 2nd little is 13 and living at Mount Rich in 1817. He dies in 1833 of "Effusion in the brain."

African born Mary Rose is the youngest saltwater slave I found. She was 18 in 1817, living at Mount Rich, which means she would have been nine years old or younger when she endured the Middle Passage. She dies at Mount Rich in 1823, age 24, in childbirth.

Others not so sad, but brief for lack of detail. What surprised me is the number of people who actually survived slavery and reached the magic year of 1834 alive. (Not so magic, of course, since they just kicked over into that apprenticeship program for four years.) A lot of entries read like this.

Kitty is an African woman, 30 years old and living at Mount Rich in 1817. She has country marks on her face. She makes it to 1834, age 46.

In 1817, Lockerby is five years old and living at Anse la Roche. In 1824, he is sold to Mount Rich. He makes it to 1834, age 21.

Or this one, for a girl named Mary (of course — Marys are my obsession today), who is mysteriously set free at the age of six.

Mary is first listed at Mount Rich in 1817, age three, one of the mulatto (white father, black mother) children. In 1820, age six, she is sold from Mount Rich to a Dr. Alexander Richard who immediately sets her free. A very surprising story. Richard was a Scottish doctor who arrived in Grenada sometime before 1817 to manage an estate his wife had inherited from her father. Several children are listed in his biography on the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of Slave Ownership database site but the language of the entry is such as to imply that all these children may not have been born to his wife. Mary is not on this list, nonetheless the fact that he bought her and freed her suggests that she may have been his daughter. Of course, after she is freed, she disappears.

They all disappeared after they became free because the powers that be lost interest in them when they were no longer a valuable commodity, an income stream, or a political issue. Most of them didn’t even have last names in 1834. Most of them simply went on working as apprentices at the plantations where they had been enslaved. It took a generation or two for surnames to take hold. After 1838, they began to earn pay for the work they did, very low pay, as you would expect. Because the land remained tied up in these old estates, there was precious little opportunity for the former slaves to better themselves. This is why there are so many expatriate communities in Canada, the U.S., and Britain. It wasn’t until the 1950s, until the general strike of 1951 and the “red sky” days when so many old plantations were burned, that meaningful land reform began.

These brief lives (I have hundreds, actually) are part of my book. I hope readers will see them as a work in progress that they might themselves extend and correct. My fondest hope is that a reader might remember an ancestor, an old family story, that will connect to someone I have written about, connect the present with the past.

Basic genealogy research can be cumbersome because of everything you have said about spelling, penmanship, etc., but this?? So complex. And every piece of the puzzle is loaded with sadness and injustice.

Douglas, I can identify exactly with your paragraph “I will tell you that the first time...”, as I went to the Records Office at Kew in 1997 to search the original documents for the name of a slave mentioned in the family. The horror of seeing all these people, from tiny toddlers to disabled elderly listed like second hand tools with defects or not, to be used or discarded at will, has stayed with me the rest of my life. I still have the A3 photocopies staff made for me.