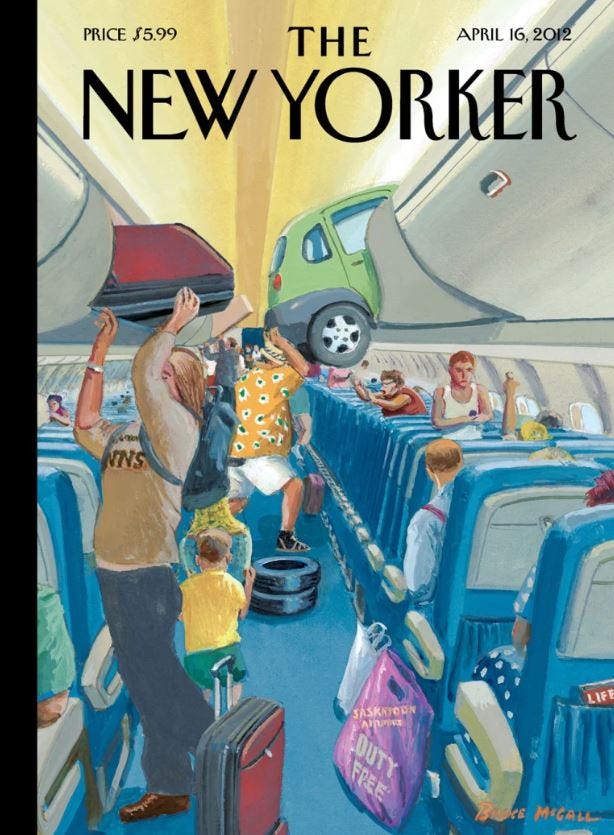

Bruce McCall died on May 5 at the Calvary Hospital in New York of the effects of Parkinson’s disease. He was a brilliant career advertising man, but most famous for his cover art and humour pieces in the New Yorker and National Lampoon. A satirist and cartoonist extraordinaire, he specialized in a style he called retrofuturism. He was also a cousin of mine. According to the genealogy app I use, he was my fifth cousin once removed — I have no idea what that actually means other than the fact that we’re both descended from a prehistoric Scottish soldier named Donald McCall (1735-1818).

McCall’s early years were spent in Simcoe, ten miles along Highway 24 from our family farm. From 1942 to 1947, he lived at 101 Union Street, at the corner of Talbot Street, just two blocks from where my mother grew up at 286 Union Street. She was a teenager when he was born in 1935, but she remembered him and his family because they lived across the street from her Aunt Jean Jackson.

Here is McCall recalling the Jackson house. This is one of his sunnier memories of Simcoe.

The substantial Jackson house sat on a hill directly facing our peeling stucco home across Talbot Street. Daredevil kids lugged their sleds up to the Jacksons’ front lawn, then dived downhill belly-first on the sleds. A Flexible Flyer, with glass-smooth steel runners, was the ride of choice. Victory went to the sledboy who eked out energy enough to keep his momentum as he reached Talbot Street and his path flattened out. — How Did I Get Here?

Mostly he remembered Simcoe and Norfolk County in delightfully scathing terms.

No Ontario town was ever nominated to be sister city to Florence, and there were good reasons why Simcoe was among the nonstarters. Scottish conservatism is as close to the opposite of Florentine culture as can be imagined. Piano lessons and church choirs sufficed as culture, which otherwise had no role in the life of the town. — How Did I Get Here?

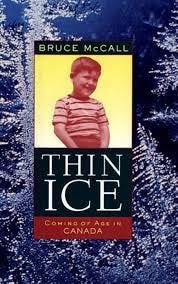

McCall escaped from Simcoe and Canada as soon as his art and wit could take him. But like many people with unhappy childhoods, he carried his past with him, providing fodder for two funny, bitter memoirs, Thin Ice, Coming of Age in Canada (1997) and How Did I Get Here? A Memoir (2020). In other words, even late in life he could not resist gnawing over the old bones.

Of the two books, Thin Ice is preferable. He starts with the ancestors, the McCalls, a populous brood of hard-drinking, illiterate Scots who, like all Loyalists who retreated to Canada after the American Revolution, came to think too well of themselves as evidenced in the family Book of Genesis The Genealogy and History of the Norfolk McCall Family and Associate Descendants, 1796-1946 by the estimable Delbert T. McCall — also a cousin — which opens with a dedicatory poem.

Dear were the homes where they were born,

Where slept their honoured dead;

And rich and wide, on every side,

Their fruitful acres spread;

But dearer to their faithful hearts

Than home, and gold, and lands,

Were Britain’s laws, and Britain’s crown,

And grip of British hands. As McCall acidly observed, “A drunk, profligate, slow-witted, or deviant McCall never appears in Delbert’s circumspect family chronicle. They are an unfailingly pious, sober, civic-minded line…” Such antecedents, real or imagined, are, of course, cloying, suffocating, and frustrating to a boy yearning for the sleek modernity of the shining metropolitan paradise to the south.

McCall’s parents married young and had six children in the howling gale of the Great Depression. They never had much money, never owned their own home. From 1943 on, his father lived mostly away from home for his work, leaving his wife alone with the brood. She reacted by retreating into drink, leaving the children mostly to their own devices. She died in 1957 at the age of 49; his father died two years later, also at the age of 49.

As a boy, McCall could only register his parents’ misery in his own misery. But later he came to see how badly things had gone for them. In high school, they had been a bright, witty, gilded couple, who started two magazines, The Mudslinger and The Ratcatcher. They were “Simcoe’s version of a smart set,” with trips to New York where they took in Broadway shows. “Nascent Jazz Babies they were, bright young things, flaming youth headed out of torpid Simcoe to find their destiny in the larger world, where they belonged.” But lack of birth control slaughtered their dreams, and it was left to the next generation, their writer son, to take the path they had missed out on.

The day their firstborn son and responsibility arrived to stay, in 1931, must have made it seems as if a line had been drawn across their lives—a line that marked an abrupt end to their carefree ways, their precocious dreams, youth and optimism and happiness itself. — Thin Ice

Despite the tragedy and disappointment of his parents’ lives, some of their flash and ambition survived in Bruce McCall. That and the inspiration supplied by the bundles of the New Yorker they read and kept in the house. Think of their dark, rattle-trap rambling house on Union Street, with the absent father and evanescent mother, in dour, conservative Simcoe, concealing this vein of ore from a completely other world. Reading the New Yorker at the age of nine, “I had stumbled upon the outskirts of a strange but clearly advanced civilization.”

From there, it wasn’t straight line to writing regularly for the New Yorker. Only in retrospect does it seem so. Suffice it to say that the boy Bruce McCall found solace from his domestic misery in drawing, in making up fantasy worlds. With a pencil and a blank sheet of paper, he was in control. Then one day, miraculously, people started paying him for his quirky inventions. And he was able to live far away from the sad scenes of his youth.

I am writing this because people in Norfolk County read my newsletters and perhaps need reminding. In 1999, I got in touch with Bruce McCall and solicited a story for the annual Best Canadian Stories, which I edited at the time. I didn’t mind that he had mostly turned his back on Canada except to make disparaging jokes. To me, that actually made him even more Canadian, ultra-Canadian. We have an entire mini-literary tradition of disparaging Canada. It’s a cottage industry. If he had kept his mouth shut, he’d have been less Canadian. In putting him in Best Canadian Stories, I wanted to mark the fact that he had become one of our foremost authors. The form — satire — is not popular in Canada; Canadians go to the United States to perform their satire. But you can see where it came from. Growing up in Simcoe in the Depression, fantasy and comedy were the survival kit, the New Yorker was his lifeline.

Here is Adam Gopnik’s obituary in the May 15 issue — “Remembering Bruce McCall, Satirist and Compleat Canadian.”

Me, a hero? Thanks, Sally. You made MY day!

Nice one, thanks!