Here’s a little essay about pandemics, frontline workers, and courage.

My grandparents’ generation lived through that earlier pandemic, the 1918-19 flu, which also came in waves, each different, the worst hitting in October 1918. Thinking of this and our current situation, I wrote an essay about my grandmother who was a student nurse in Toronto General Hospital just before the flu struck. Luckily (as it seems in retrospect), in the weeks before that catastrophic October outbreak, she fell dangerously ill of something else entirely, nearly died, and had to be sent home to recuperate. But her friends at Toronto General were in the thick of the response. On October 22, just as the flu reached its peak, a student nurse, known only as Jigs, wrote my grandmother a letter warning her not to come for a visit she had planned. The letter is startling in its stoicism and its horror. Death really was stalking the corridors of the hospital. This essay came out in the print magazine Canadian Notes and Queries (Issue #107 Spring/Summer 2020). A few of you might have seen it, but many not.

A curious story that did not make it into the essay for reasons of frame and focus has to do with how my grandmother got sick in the first place. Her troubles began when she was assigned to the infamous Ward H. Ward H at Toronto General Hospital was a special diabetic clinic established by a Dr. Walter "Dynamite" Campbell where Banting and Best did their crucial early experiments with insulin two years later in 1921. The patients were treated by restricting their diet, essentially starving them to save them from dying of diabetes. My grandmother called them “sippy diets” because they were liquified and meant to be sipped in small amounts, not eaten. The nurses spent hours in the food prep area of the ward mixing these concoctions specifically designed for individual patients. That ward work and the emotional labour of caring for emaciated, starving patients, mostly terminal, was grueling for the young students. In my grandmother’s memory, almost everyone assigned there came out of the ward sick themselves. As did she.

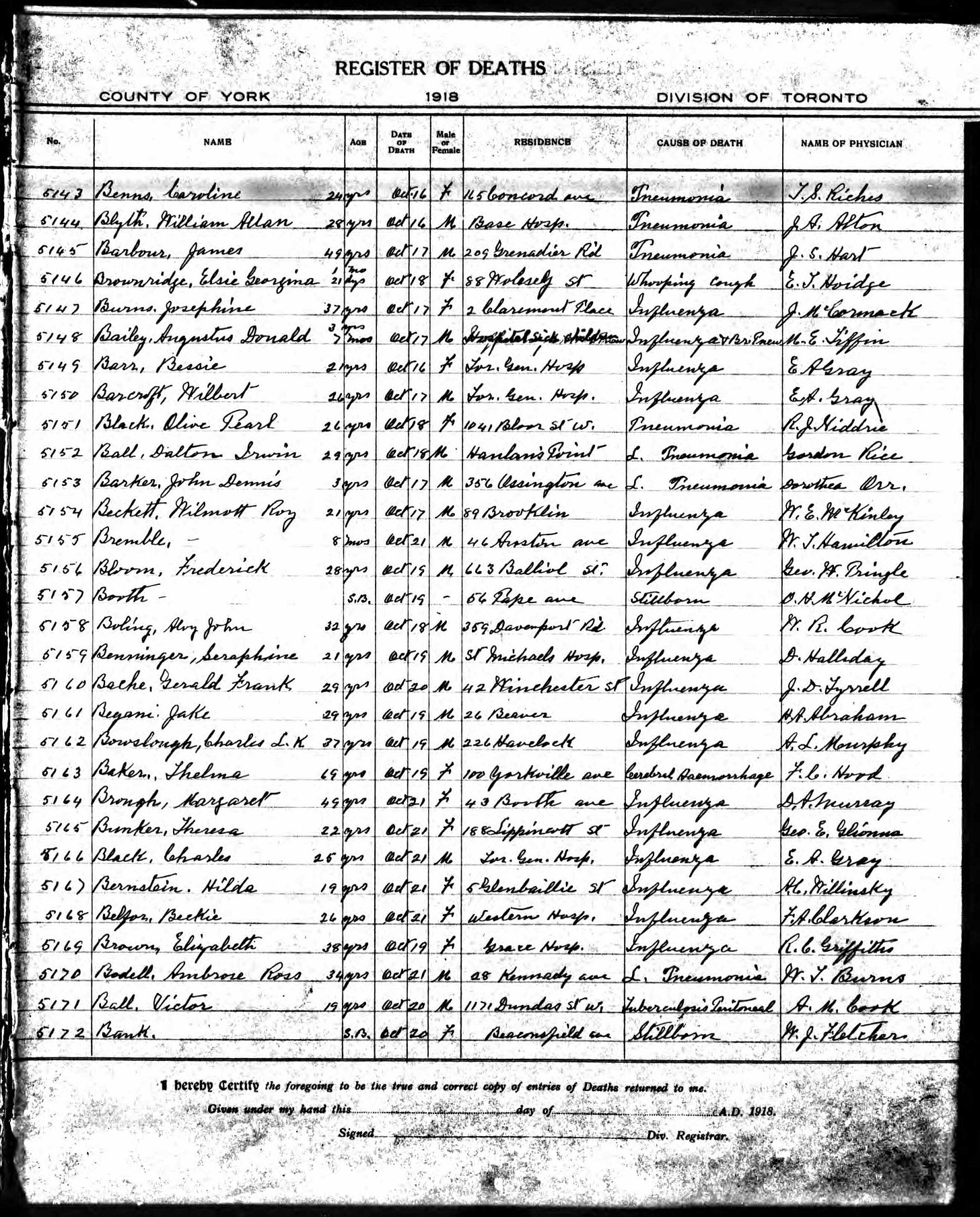

Another side note, also not in the essay, is that my grandmother’s Uncle Walter, Dr. Walter McInnes, died of the flu in early 1919. He had fought the disease in his patients, exhausting himself, but managing not to lose a single case until the tail end of the wave, when a young father with a large family succumbed. The family story is that the disappointment broke Uncle Walter. He died so quickly that he and the patient are next to each other on the death registry.

My grandmother grew up in St. Williams on Lake Erie. Uncle Walter practised in nearby Vittoria. These are tiny places in Norfolk County, Ontario. The easiest way to locate them is to look at a map of Lake Erie and spot that unmissable extended point coming out of the north shore, roughly across from Erie, Pennsylvania. That’s Long Point. St. Williams is on the shore of Long Point Bay. Vittoria is a farming village a few miles inland. This is old Loyalist country, settled from the 1790s on by Americans who wished to remain under British rule. It was much damaged by American raiders during the War of 1812. For me this is all magical territory, land of legend and heroic beings.

At the beginning of 1918, my grandmother, Kathleen Brock, known to her friends as Pete, was a student nurse at Toronto General Hospital. Strep throat sidelined her that spring. The doctors sent her to the pneumonia ward, where they kept the windows open despite the cold. Then they isolated her in the diphtheria ward. Then they took her tonsils out. Then they diagnosed nephritis. After thirteen weeks in the infirmary, Pete and her inflamed kidneys were furloughed home to recuperate, a circumstance that may have saved her life.

On October 22, at the peak of the city’s Spanish flu pandemic, her friend Jigs (the only name I have for her) stole a few minutes from her hospital duties to scribble a note warning my grandmother not to visit. Then she went on to describe her isolation amid the overflowing wards, the prayers, vigils, deaths, and funerals. Her words are grim and stoic, her affect flat, she had no one else to confide in. “I will begin with our class,” she writes. “Jean Thistlethwaite died with it Sunday at midnight. There was a funeral service at Miles Undertaking Chapel last night for the nurses & doctors.”

She sketches her scenes pell-mell, one on top of the other, but with an unconscious grace that comes from acceptance, from lack of self-regard—a father arriving late to say goodbye to his daughter, a pair of student nurses dressing their classmate’s body for burial, a friend given up for dead but still struggling with pneumonia, morning prayers with the nurse superintendent in a room used to store displaced furniture, another friend buried in her uniform with the coveted black velvet band sewn to her cap signifying graduation.

Born in 1896, my grandmother grew up in the southern Ontario hamlet of St. Williams, which sits atop a clay bluff overlooking Long Point Bay on Lake Erie. She lived in a gracious, ivy-cradled brick home with a sweeping veranda and an untamed garden in back called the Wilderness, just steps from the family mill and furniture factory. She had a younger sister named Jean and two live-in maiden aunts, and life was idyllic: hot, dreamy summers, school dramatic productions and skating parties come winter. But in 1914 her father killed himself with an overdose of laudanum, turning her life upside down. The sisters needed something practical to do. Jean went to Normal School in Toronto to be a kindergarten teacher, and Pete chose to enroll at the Toronto General Hospital’s nursing school.

This fit a broad pattern at the time, a moment of awakening for women. The war was on, plenty of men were already overseas or training in camps and armouries around the province. Young women caught “nurse fever,” a desire to join up, don a uniform, and make a contribution. At the same time, nursing had been undergoing a transformation from its lower-class beginnings. The Toronto General Hospital Training School for Nurses was putting a special effort into recruiting rural middle-class girls with an education to help professionalize the calling. Isabel Sparks was a piano teacher from St. Marys, a doctor’s daughter. Athol Beatty had graduated from Albert College in Belleville. Poor Jean Thistlethwaite was from Prescott, Betsy Barr from North Bay, Hope Aylesworth from Newburgh, and Margaret Pelton from Atwood in Perth County. Maud Gordon Lovell, an exception coming from the city, was in the Toronto Blue Book, a sorority sister, and a University of Toronto graduate in 1914. Some, besides my grandmother, had already known tragedy. Isabel Sparks’s fiancé, a surgeon in the Royal Army Medical Corps, had died at the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

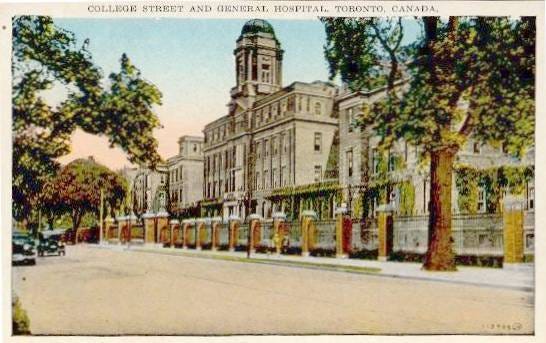

Toronto General Hospital had relocated in 1913 to a resplendent beaux-arts building on the south side of College Street at University Avenue; not the full expanse but a core that eventually became known as the College Street Wing and is now home to the MaRS Discovery District. It was characterized by a dramatic central administrative block, constructed of honey-coloured brick, with a domed tower and inset balustraded terraces on either side. Three-storey ward pavilions extended south from the building’s rear, each with open-air balconies at the tip. This was before public health insurance, so the complex included—besides the public wards (520 beds)—roomy, hotel-like accommodations for private patients (150 beds). Red battleship linoleum made in Scotland covered the floors.

The nursing school followed the English Nightingale teaching method, which combined practical ward work with classroom study, three years of eleven-hour days, five and a half days a week. Students took classes in anatomy, physiology, communicable diseases, surgery, obstetrics, and dietetics, and in their third year graduated to working on the wards full-time. They lived in a residence on the hospital campus, with sitting rooms on each floor and an in-house medical library, strict rules and morning prayers. Probationers and pupil nurses were unpaid, but given room, board, and textbooks. As the young women moved up, their uniforms changed. At six months they got cotton caps, bibs with straps and pins, shirts with stiff cuffs up to their elbows and a narrow, upright collar. And at the end, as full-fledged nurses, they sewed the black velvet band on their caps.

The 1918 pandemic was known as the Spanish flu despite the fact that the first cases appeared that spring at an American army base called Camp Riley in Kansas. Over the summer, the virus mutated into a deadlier form, which began to spread in September from yet another American army base. The mutated virus slipped across the border into Ontario at Niagara, first striking a training camp at Niagara-on-the-Lake. By late September military authorities were rushing difficult cases to Base Hospital, as it was called, housed in the abandoned Toronto General Hospital building on Gerrard Street East, by then decrepit and understaffed. On September 29 a schoolgirl died at Toronto General Hospital, the pandemic’s first civilian fatality.

The flu hit the city with such speed and ferocity that the medical officer of health likened it to a cyclone. Schools were closed, large public events canceled, theatres and sports venues shut down. The city added extra streetcars to thin the crowds of passengers. Women took to wearing a chiffon scarf called the Spanish veil. Lines of horse-drawn hearses appeared in the streets. On October 12, according to the Toronto Star, 46 of 211 nurses at Toronto General were sick. Ten days later, Jigs writes that sixty or seventy nurses are off.

“A week ago yesterday Hope Aylesworth died (the day she was to have had her black band so they buried her with her black band on her cap). They had a service at Miles [Undertaking Chapel] for her. On Tuesday Bessie Barr died. She was in Bertha Knox's class & used to room on fifth floor. They have been expecting Gretta Ross to die for nearly a week. On Friday she was nearly gone & had interstitial [pneumonia] & she is still holding her own…”

The hospital was reorganizing on the fly. “All third floor I, F & C are isolated Flu wards, so are E & H. also 2nd & third floor of the pavilion.” The nurses who died had been moved to the second floor of the private patients’ pavilion, reserved for desperate cases. At the nurses’ residence, new flu cases were isolated in the basement dorm rooms with two special nurses and three students always on duty. The displaced residents crowded in where they could. “The sitting room on 2nd is also full of beds. They moved the piano & Victrola to the Reception Room, so we have prayers there now.” Everyone was concerned for the nurses. The school superintendent, Jean Gunn, urged them at least to walk around the hospital grounds if they could find a half-hour. Doctors and well-off citizens sent cars to take them for drives. There was never any time to dress. They just threw their coats over their uniforms and went.

“Poor Miss Gunn,” writes Jigs, “it is so hard on her. She spoke to us at prayers the other morning & asked us to ‘Carry On.’ She said we were facing now something like our army in France is & although our comrades are falling we must go on for the others. She said the nurses who had gone didn't need us anymore, but those living did. She broke down twice while speaking to us.”

This is a story about women. It impresses me how few men are mentioned in the letter. Jigs and Pete were special friends, bonded in the way young women bond when they live together away from home, encounter a city for the first time, and share the hardships, joys, and rites of arduous schooling. “I know you will understand how blue we are all feeling,” she writes. “I thought you would like to know & felt I must tell all our troubles to someone as I couldn't tell them at home, for they would worry more than ever.”

I cannot tell you what happened to Jigs. I do know that Gretta Knox did not die as expected. In 1934 she was the first public health nurse hired when Easter Seals started its direct nursing program in Ontario. Gordon Lovell and Athol Beatty were in the first class to graduate from the University of Toronto’s new Public Health Nursing program in 1921. On March 6, 1933, Isabel Sparks joined fifteen of her classmates for a reunion dinner in Toronto. She worked at Toronto General until she retired.

My grandmother was married in 1919 to an English food chemist who had started a jam factory in St. Williams. He was forty, she was twenty-three. The story is that when he came courting , no one was sure at first sure which eligible female he was after: Pete, her sister, or their mother. On her wedding affidavit, under the heading Occupation, she wrote one word—“nurse.”

So it is a small world Maud Gordon Lovell, a descendant of John LOVELL , the Montreal publisher of many directories an the Literary Garland is also connected to Beemer Glover line through marriage. B.

These recent stories feel like the ingredients for a memoir. My grandmother lived through the flu pandemic in Chicago. Being the quiet sort, she never said much about it and didn't keep any records as far as I know, but she was my favourite and when I could not track down many paper details of her life, I made up a story for her that was the stuff of my last novel. It is interesting to think of how "they" went through what we are going through now, but sans internet, cell phone Uber eats, etc. I found myself hungry for the social cultural history of that time, so thanks for this.