Here is an essay about my great-grandfather John Brock who fancied himself a poet and committed suicide in March 1914. The essay was published a while ago in the print magazine Canadian Notes & Queries (Issue 115, 2010), so not likely to have been seen by anyone recently.

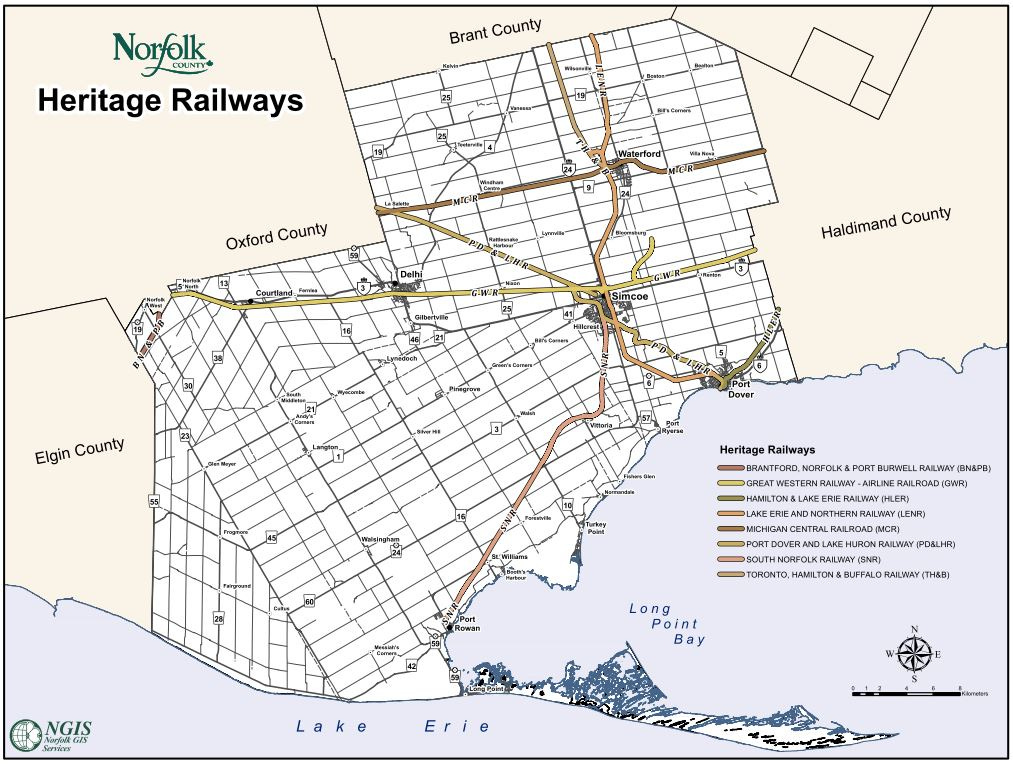

All my family essays share a locale, Norfolk Country, Ontario, a patch of post-glacial sand plain on the north shore of Lake Erie, roughly from Long Point in the west to Port Dover in the east. If you look at a map, Long Point is that unmistakably phallic peninsula jutting into the lake across from Erie, Pennsylvania. Simcoe, about 20 kilometres inland is the county seat. It’s where my mother grew up and her mother and grandmother died. But the main family reference points are the village of St. Williams, situated on a bluff overlooking the Inner Bay of Long Point, and Vittoria, a village between St. Williams and Simcoe. My McCall and McInnes ancestors settled in and around Vittoria between 1790 and 1840, my genealogical branch moved to St. Williams in the 1860s.

The Long Point area has a history that reaches into antiquity. It’s very common to find stone artifacts in the fields roundabout that date back hundreds of years. When the Jesuits arrived in the 1600s, they found extensive villages belonging to a Iroquoian people they called the Neutral. But shortly thereafter, the Seneca from what is now upstate New York wiped out the Neutral (with the help of diseases brought by the Europeans) and the land became mostly uninhabited, used as a Seneca hunting ground. The Seneca, like the Neutral, spoke an Iroquois language. Shortly after that (all this took place in a few short decades), the Mississauga people (they spoke a quite different Ojibwa language) descended from the north and pushed out the Seneca hunters. Oral traditions speak of a large naval battle (in canoes) fought off Long Point, in which the Seneca took a drubbing.

In the 1780s and 90s, a wave of United Empire Loyalists crossed the border from the United States (think of them as analogous to the Cuban refugees who came to Florida after Castro came to power in Cuba) and took up land granted to them by the British colonial government. This became what was called the Long Point Settlement, much of which is now Norfolk County. These Loyalists founded the little towns and villages I am writing about, St. Williams, Vittoria, Port Dover, Simcoe and so on. In the War of 1812, the area became a battleground of sorts. Militia from Norfolk joined Sir Isaac Brock and sailed with him up the lake to capture Detroit. An American fleet destroyed Port Dover. Another American raid, conducted by Kentucky militia on horseback, burned all the mills except one, drove off horses and cattle, fought skirmishes, and generally terrorized the place (as far as I can tell they rode right past the farm where I grew up, except that the farm wasn’t there yet).

I’ve written several Norfolk County short stories and essays. A chunk of my novel The Life and Times of Captain N. takes place along the Erie shore. This essay about my great-grandfather was once meant to be a novel called Lost Letter, Book of Dreams. Its genesis is interesting. The fact that John Brock committed suicide was a deep family secret. His ancient widow, my great-grandmother always said he died of diabetes. My mother only learned the truth when a friend of her mother inadvertently let it slip. “Oh, I thought you knew,” she exclaimed. My mother couldn’t (how families work) face her mother, so I was deputized to go and ask. It was an astonishing and mysterious moment. I asked and my grandmother just broke out, sybil-like, not meeting my eyes, but blurting out the whole story, even reciting the Robert Burns poem he had quoted in his suicide note. She was relieved, it seems, to have the whole thing come out.

That suicide letter is also interesting. My mother knew about it from her mother’s friend. She was sure her mother had it. I asked. No, my grandmother didn’t have the letter, but she thought Cousin So-and-So did. I asked. And, no, he didn’t have it either. It had disappeared, yet my grandmother could remember it, almost word for word. Years passed. I was living in a cabin in the woods in upstate New York near Saratoga Springs, when a thought occurred to me. Why not go around and interview old people in the village and see what turns up? An acquaintance provided me with a starter list of names, and I began making cold calls to St. Williams. One of the names was a Victor Leedham. I phoned Victor one afternoon and explained my mission, that I was researching John Brock’s suicide. Victor was elderly; you have to imagine his slightly high-pitched elderly voice. “Well, no. We don’t know anything about that.” We chatted; I temporized. Then I probed again. “No, we don’t know anything. We don’t talk about things like that.” I knew he was keeping secrets. I gently pressed. “I don’t know anything,” said Victor, then he paused and added thoughtfully, “The wife has a letter.”

My excitement started to rise. Actually, as soon as he mentioned the word “letter,” I somehow knew what it was. I cagily chatted a bit more, then asked Victor if I could speak to his wife. She came on. I don’t want to make fun of these people. They were gentle and genuine. They were also tied to a taboo of the past. I could sense that they were afraid of uttering the words. We don’t talk about that kind of thing. So the conversation had to continue by avoiding that-which-cannot-be-said, but saying it nonetheless. Victor’s wife and I chatted amiably and, yes, she agreed that she didn’t know anyhing about John Brock’s suicide. She had been a little girl at the time. She didn’t really know anything. Then I said, “Well, Victor mentioned that you have a letter that might have something to do with John Brock.” “Oh, no,” she said, emphatically. “I don’t have a letter.” “Well,” I said, “if you DID have a letter, would you ever think of letting me see it?” She said, “I don’t have anything.” But her voice told me she was relenting. “Mrs. Leedham,” I said, “if I drove up there and came for a visit, would that be okay?” “Oh, I don’t know…”

A month later I was at the family farm. I drove to St. Williams and the Leedhams showed me the original suicide letter. They had even made photocopies, since they didn’t want me to take the original. She didn’t know how she had gotten the letter (so she said), it had simply appeared in her family Bible. That was all I could get. But I had John Brock’s words, his handwriting.

The Possum

My great-grandfather John Brock killed himself with an overdose of laudanum in St. Williams on the North Shore of Lake Erie in March, 1914, the day before he was to appear in court to answer a charge of alienation of affection and criminal conversation. This was in an era when marital rights yet bore the flavour of property rights. Alienation of affection and criminal conversation referred to actions that deprived someone of his or her spousal relationship. In practice, the phrases meant anything from merely counseling a wife to leave her husband and thence to seduction and adultery.

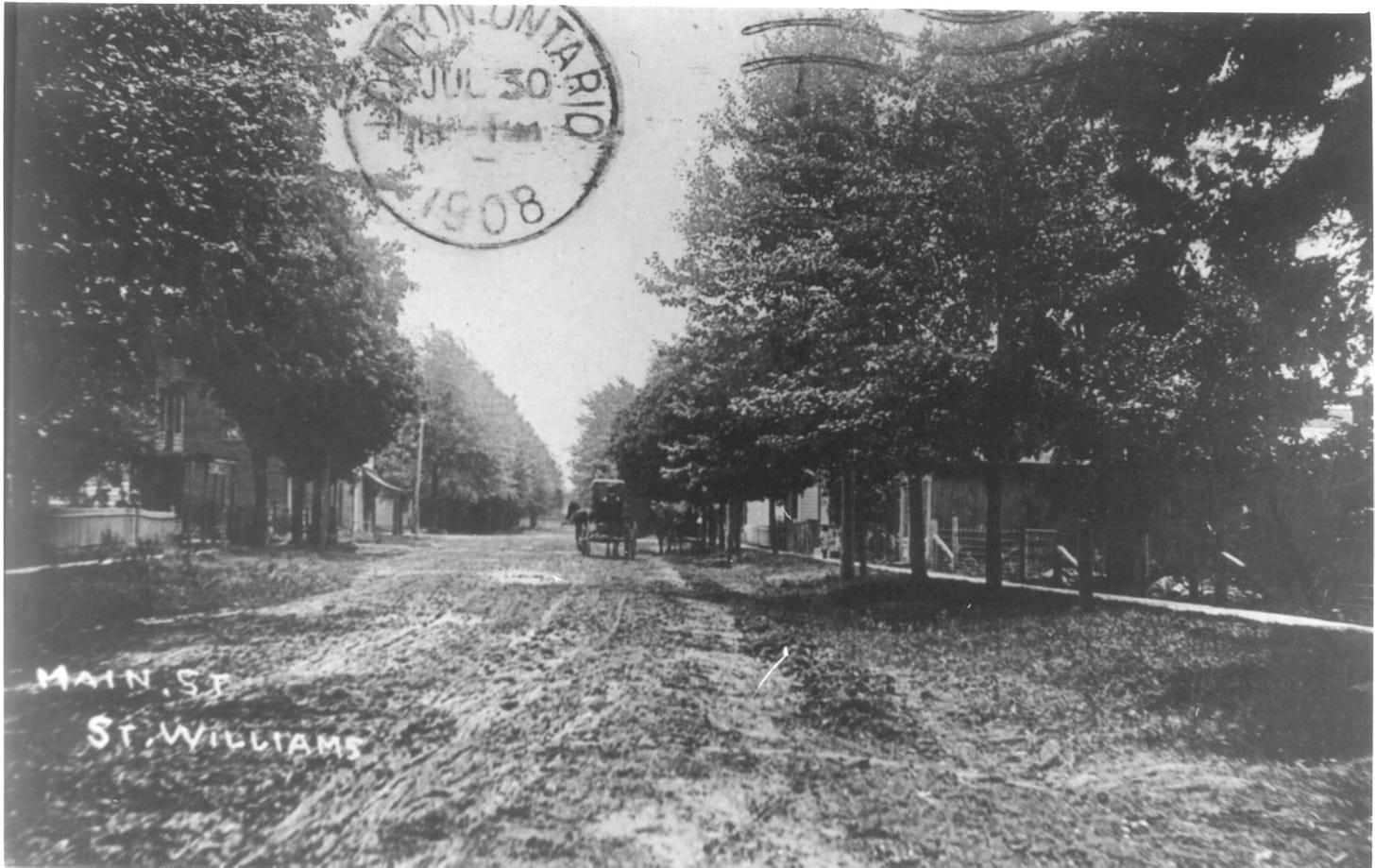

Today St. Williams is a sleepy hamlet on a sand and clay bluff overlooking the Inner Bay between Turkey Point to the east and Long Point to west, a beautiful and mysterious place, in summer especially when the lake surges languidly under the harsh sunlight, and the trees on the point shimmer like a mirage along the horizon. In the early 1900s, lotus beds choked the shoreline and the bluffs were scrubby and bare except where the remains of the great timber flumes swooped down to the beach. For years, the McCalls (my mother’s family) had been engaged in lumbering, furniture making, boat building and general retail, but mostly, as my mother’s father once observed, in shipping all the forest roundabout across the lake to Cleveland and Buffalo.

In 1914, the farms around St. Williams were turning to blow sand and dunes, and the McCalls turned necessity into virtue by lobbying the provincial government to buy their land and open a reforestry station to help put the trees back. The family businesses had been in gradual decline since the depression of 1873-78; we were the early victims of what is now called globalization, in this case the first wave of corporate bloat and centralization that coincided with the late Victorian era. When the railway finally extended a tentacle through St. Williams in the late 1880s, instead of inspiring a boom, it sucked all the money out of the village overnight. But in 1914 the family still thought a lot of itself, and those homes, with ivy crawling up their sweeping verandahs, stood with immaculate hauteur against the internal erosion of the economy and ecological ruin.

In the 1880s, John Brock came to St. Williams to clerk in the McCall & Co. general store. He married the boss’s daughter, my great-grandmother Sarah (Sadie) McCall, a thin, stern-looking girl with pinched lips and an air of fashionable elegance. The McCalls were Loyalist descendants of an illustrious Highland soldier, who fought with Wolfe at Louisbourg and Quebec and settled in Canada after the American Revolution. McCalls fought in the War of 1812. They cut trees, multiplied, and went into politics–another family timber baron, Alex McCall, was a Tory senator in 1914. We have a hand-written note from Sir John A. MacDonald among the family heirlooms.

In this world of nascent capital, ascendency, and cronyism (in the 1880s, the railway company board was stacked with McCalls and their in-laws), Brock was always an outsider, a clerk and manager, never an owner. He was the son of a virulently Orange north of Ireland Protestant blacksmith and carriage builder, who, paradoxically, married a Catholic farm girl, probably because she was already pregnant, and sired a brood of darkly handsome young men. Eventually, the sad couple split up, and John Brock’s mother went to live with her Catholic relatives. In 1906, when she died, he volunteered to escort his turbulent father to the funeral. The old man balked at entering the church, heard the rites through a window, and said after that it was just like a circus inside and “the priest was the biggest clown of all.”

Somewhat mysteriously, after his mother died, when he was in his early forties, a father twice, a prospective Conservative candidate for the House of Commons, John Brock started writing poetry. He twice published verse in the Toronto Mail and Empire, wrote imitation W. H. Drummond habitant poems, verse letters, fishing stories, village anecdotes, and character sketches. They are mostly one step up from doggerel, but intended for fun, or so he always said, and valuable as social documents if not revealing in other ways as well.

The Possum to himself thus mused,

“My rhymes I hope will be excused.

I’ve laboured for a month or more

At nights and sometimes in the store,

And even after going to bed

I’ve run a few lines through my head...

He liked to call himself the Possum (he called himself the Bard as well); he kept a stuffed opossum in his store abandoned in lieu of cash by a black deck hand who came in off a lake boat one day and then disappeared. Opossums are primitive marsupials that protect themselves from predators by pretending to be dead. This is what I think John Brock had to do growing up in that blacksmith’s house, all psychic violence, bigotry and sexual undercurrents, and then marrying up into the St. Williams village aristocracy (already, unbeknownst to itself, on the way down), Waspish provincial Anglophiles with an attractive air of entitlement. Once a Jehovah’s Witness knocked on the door and asked if they had been saved. Aunt Maggie McCall, born in 1857, is reputed to have said, “Why we go to the Anglican Church and always vote Conservative. Of course, we’ve been saved.”

In 1911 Brock wrote and directed a musical play called Diamonds and Hearts which was meant to be a one off fund-raising project for a new town hall to be built on a lot Brock had donated to the community. No one remembers what this play was about (seems like a card game was involved), but it was such a success it went on a little tour of the surrounding towns. And Brock, who must have been in a manic phase, shipped in oysters by train for a town picnic to raise even more money for the town hall which, at the time of his death, was supposed to be named for him, although this plan was quietly dropped in the aftermath.

Then something happened, a mysterious psychic shift, cataclysmic, secret and fatal, of which you can only see faint intimations in photographs from the time. In his prime, John Brock appears as a jaunty handsome broad-faced gentleman in a dapper summer suit and straw boater with a croquet mallet in his hand. Later photographs show him in decline, losing weight, his eyes hollowing out. A sad stare replaces the confident smile.

A haggard look came in my eye

To see me thus my wife did sigh.

Wild dreams disturbed my rest at night

Strange visions...

In October, 1913, a neighbour named Art Aker served legal papers to John Brock on the board walk in front of his store. In a pencil letter to his lawyer, Aker described the scene:

I put the two papers in an [sic] sealed envelope. Walter McCall [Brock’s brother-in-law] & Brock were talking in front of the store I walked over & gave B the Letter & then I went to the Station when I came back Brock stood on his side of the Street about half way between the two Crossings. he asked me to come over. I told him if he wanted to see me to come here. He came right through the Mud to me and said what do you mean when I first looked it over I thought it was a Joke tell me what you mean. I told him to go to Kelly [Aker’s lawyer] he would likely tell him He said if he seen anybody it would be somebody else. He said he hoped I had not said anything to any body as it was an awful thing. that I was very much mistaken.

Art Aker was a local fisherman who drank too much and ran party boats from the landing below the bluff--fishing, shooting, and carousing expeditions to the Long Point lagoons across the bay. He had five daughters and a wife known as Lib or Libby, whom my grandmother described as fat. But I have seen a photograph of her stretched on the prow of Aker’s boat like a sea nymph–she wasn’t always fat, and there is a careless eroticism to these North Shore fisherfolk, driven by sultry summers, that milky Lake Erie sunlight, and alcohol.

When he was younger, Aker had learned the cheese-making trade and, borrowing money he seems not to have paid back, bought the village cheese factory next to the railway station. But his illusions of grandeur fell to pieces with the local economy and his own improvidence. Brock tried to sell his cheese in the family store, and I think Brock’s failure to save Aker from failure planted the seed of resentment, ressentiment, the spirit of the coming age.

I’ve read Aker’s letters to and from his lawyer; the lawyer constantly harps at him to find some evidence of infidelity, evidence which never seems to materialize. My grandmother Kathleen, John Brock’s daughter, said no one in the family ever believed he had an affair with Libby Aker. One of Aker’s nieces told me that Harriet, Aker’s youngest daughter, once said that Brock and Libby had been seen going for walks together; in those days, “walking” was still slang for courting or dating. An elderly St. Williams matriarch, a Methodist, the opposite party in a church-ridden town, said Brock killed himself to prevent public exposure of an earlier indiscretion, a child born to a girl who worked in the family store. A cousin of my mother’s told me Brock had several affairs; a woman who made hats rented a room above the store and Brock was up there more than he was minding his own business.

I trust none of these stories, all small town spite and envy. I don’t trust my grandmother’s story either, though I believe she thought she knew the truth. By all accounts John Brock was a cheerful, jovial, well-liked man. More than once I heard him called sensitive, a code word for something I can no longer decode. My grandmother’s memories were fierce and adoring. He was a mimic and liked to play tricks. In his younger years, he wore a huge droopy moustache. One day he shaved it off, knocked on Walter McCall’s door and, assuming an accent, visited with McCall’s wife on the porch without being recognized. Sadly unrecognized perhaps, the Possum pretending.

He loved male camaraderie, loved the annual July bass fishing trips to the Point with his cronies, but he lived in the old McCall house with five women, his wife Sarah McCall, her two spinster sisters, Emma and Maggie, and the two Brock daughters, Jeanette and my grandmother Kathleen. Sarah had given birth to a son a year after they were married, but the boy died at three of pneumonia. When John Brock died, he owned almost nothing; the general store he operated and the house belonged to his wife.

In the weeks before his trial, the tempo quickened. Brock’s lawyer, a man named Slaght from the county seat in Simcoe, rode the train to St. Williams to take depositions. Aker’s letters at this time betray desperation. He hears about a man who saw Mrs. Aker (he always refers to her as Mrs. Aker) and Brock together in the night but he doesn’t know the man’s name and can’t locate him. He wants his lawyer to hire a detective to follow Brock and Mrs. Aker. He can’t find the money to pay his legal fees, goes hunting for support. Then suddenly another mysterious turn: just days before the trial Mrs. Aker and her eldest daughter travel to Simcoe to see Slaght in his office. No one knows why.

The night before the trial Brock sits scribbling at the dining room table. Later he stumbles into the narrow downstairs bedroom. Everyone remembers Sarah’s words. “John, are you drunk?” Laudanum, being a mixture of opium and alcohol, causes inebriation first; death comes on more slowly as the opium shuts down the autonomic nervous system.

Someone raced for a doctor, though apparently none could be found in time (alternatively, a doctor did arrive but had neglected to bring his stomach pump). Men of the village rushed through the night, even the Methodist enemies, crowding the long downstairs hallway, under the pressed tin ceiling, taking turns supporting Brock on their shoulders, walking him up and down. Someone sent out for eggs. I don’t know why. It’s just part of the story.

My grandmother Kathleen, who was eighteen, crawled into his bed, clutching him in her arms, whispering urgently that he could live if only he wanted to. She remembered him scribbling at the table and asked him where the letter was. With a hand, he indicated that it was beneath his pillow.

He died in the morning. He was just fifty years old. In a strange convergence of melancholy vectors, it was twenty years to the day after his infant son had died. Kathleen’s life was blasted. The McCall’s aura of superiority and entitlement was rocked by scandal and tragedy, never to recover.

A fisherman named Helmer bought space in the Simcoe newspaper to announce that he had not loaned Aker the money to prosecute Brock. Townsmen called in their debts; the sheriff seized Aker’s boat and fishing gear. The day of the funeral Libby Aker kept her daughters inside, shut the window blinds, refusing even to let them peep into the street.

But then Sarah started telling everyone John Brock had died of diabetes. She lived to be a hundred and one still telling the bland lie. The new town hall got someone else’s name. The outpouring of communal shock and disbelief gave way to silence. The story went underground, not to be mentioned by anyone in the family for almost seventy years.

In his last letter, John Brock wrote,

It is hard to part with my dear wife and girls. I hope they will survive the shock of my death. God protect them. Those who have driven me to this receive their just reward. I have no fear of Death.

"But I have seen a photograph of her stretched on the prow of Aker’s boat like a sea nymph–she wasn’t always fat, and there is a careless eroticism to these North Shore fisherfolk, driven by sultry summers, that milky Lake Erie sunlight, and alcohol."

Amazing, Douglas. And you look just like him.

Such a vivid picture of the place and the period...milky sunlight of Lake Erie.