A Tale of Two Sisters

The unconscious bias of history is that racial purity is the norm, whereas in fact genetic mixing is universal. We are all mongrels. Race is a social construct. Identity is less a fact than a matter of discourse, performance, and the chance of birth.

The planters in the British West Indies followed the pattern, taking purity as the baseline. They had a more or less standard terminology for various degrees and vectors of genetic mixing, mulatto, mustee, mustefino, cabre, etc. There are several instances of mulattos and mulattresses on the estates I have been studying (Anse la Roche and Industry on Carriacou and Mount Rich on Grenada), but two in particular loom darkly out of the mist of time, sinister and sad, but with startlingly divergent outcomes.

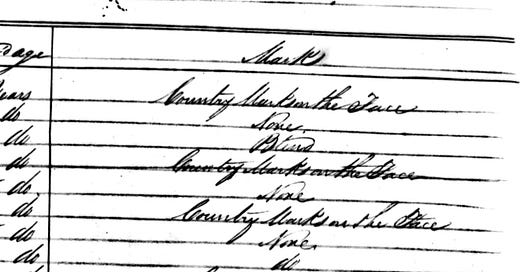

Among the people enslaved at Mount Rich in 1817, the year the British government began requiring annual plantation censuses, there were two young women, Betsy, who was 20, and Jeannie, who was 22. They were likely born on the estate, Jeannie in 1795, Betsy in 1797. The absentee owner at that time was a Scot named Henry Davidson, but the estate for many years was managed by another Scottish family named Junor who lived in the great house. Both Betsy and Jeannie were mixed race, what were called mulattos, which meant they had white fathers and black mothers. Calculating the probabilities, I suspect that Jeannie and Betsy were sisters. They may have had the same mother and father.

Also in 1817, the Mount Rich slave register included two “mustees,” two-year-old Anne and five-month-old William. On the planter color scale, mustees (sometimes called mustifs or mustives) were the children of a mulatto and a white parent (the word is a clipped version of the Spanish “mestizo” derived from the same root as the Canadian word “métis”). The births of Anne and William preceded the introduction of annual slave censuses, so I can't name their mothers with any certainty; but probably they were Jeannie and/or Betsy, since they were the only mixed-race women of child-bearing age on Mount Rich at the time.

Anne died in 1818 of "dropsy" at the age of three. Dropsy is an old diagnostic term for edema of various kinds, that is, with various etiologies, in this case possibly a version of beriberi which stems from a Thiamine (Vitamin B1) deficiency. William died a year later, at the age of two, of “fever & dropsy.”

In 1821, both women gave birth, and both babies were similarly classed as mustees. Jeannie named her daughter Peggy; the little girl only lived five months, dying of “fever & marasmus.” Betsy named her daughter Diana. She survived infancy, only to succumb to marasmus at the age of ten.

Marasmus is a disease of malnutrition characterized by wasting, alarming common among the children of the plantations. When I say malnutrition, I need to be careful. The planters did not intentionally starve their workers to death, but what was supplied in bulk likely did not provide a full panel of nutrients necessary for good health. Corn, especially, is a deceptive food and was commonly supplied to the people on the plantations. Corn-based diets, notably across the American South where pellagra was once common, are notorious for deficiency problems.

In 1822, Jeannie had another mustee daughter, Jean, who died of convulsions after 26 days.

The fact that all these children were mustees suggests there were one or perhaps two white men involved. Perhaps each woman had a white partner (one can only guess at the emotional nature of these relationships).

In 1825, both women had babies again. Jeannie bore another daughter she named Margaret little, also a mustee, the child of a white father. (The diminutive “little” or “petit” was often added to names usually to signify that there was an older person around with the same name. It’s not a surname.) Betsy's daughter was called Christiana. She was a mulatto, which means her father was possibly another mulatto. This suggests that after having two children with the same man, Betsy’s relationship was broken off. Either her white lover died, left the plantation, or spurned her, after which she partnered with a new man, probably another slave. Betsy delivered a son in 1829, this time with yet another lover. Unusually, the boy was given a full English name including surname, Alexander Taylor, and categorized as a "cabre," which means his father was black.

During my research, I chanced upon a notice on an Ancestry.com message board that opened up some intriguing if nebulous possibilities. It seems there was a Scot named James Taylor working at Mount Rich in the early 1800s. He had a Scottish wife who bore him nine children. At least one son, John Taylor (1800-1819), was born at Mount Rich. His other children are only given as a list, but among them is a boy named Alexander. For some reason Betsy picked this name for her own child, but since he was a cabre, his father could not have been white, could not have been one of the Taylor men. Perhaps she had some special affection for this white Alexander Taylor, perhaps she had cared for him as a domestic servant. Of course, this is only speculation.

Together the two women had at least eight children, with a mortality rate that exceeded 50% — the children died of dropsy (two), marasmus (two), and convulsions. One died at 26 days, the others at five months, two years, three years, and ten years. This conforms to a pattern, typical of West Indian sugar estates, where malnutrition was endemic and children struggled to survive through infancy. Yet most of the child deaths were not caused directly by malnutrition. At Mount Rich two of the biggest child killers were whooping cough (an epidemic in 1830) and tetanus (called jawfall, probably caused by unhygienic birthing practice).

Betsy was 36 in 1834 when Britain emancipated the slaves. Along with her surviving children, Christiana and Alexander Taylor, she was still listed on the estate books. To be clear, she wasn’t exactly made free in 1834. She would spend the next four years as a so-called “apprentice” still attached to Mount Rich, only a small step up from slavery.

Her sister Jeannie’s life course bent in an astonishingly different way. In 1827 seven years prior to the general emancipation, Jeannie and her surviving mustee daughter Margaret were set free. I can find no reason in the record, just the word “manumitted” next to their names. Their freedom cost £148 10, but I have no idea who might have paid for it. The most likely explanation is that the white man who fathered her child had raised the money. But it is possible that Jeannie was intelligent and industrious enough to earn the money herself. This happened on the islands, but rarely.

In moments of revery I think of Jeannie and Betsy on the model of Elinor and Marianne Dashwood in Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility. Jeannie was more measured and steady in her approach to life. She seems to have had a long standing relationship with one white man and gave birth to two (or three) children with him, fostering a relationship that led her to freedom.

Betsy was younger, more impulsive. She had children of three different color combinations — mustee, mulatto, and cabre — which means she had sexual relationships with at least three different men. Betsy’s relationship inconsistency probably prevented her from amassing the social capital inherent in the idea of family, social capital she might have leveraged, as her sister did, to win her freedom. She remained a slave until emancipation.

But Jeannie was also just lucky at a crucial junctures in her life. Luck is not something one usually associates with a slave’s life. Her story offers a little light, a tiny variation on the relentless desperation of the general fate.

And I should be careful not to judge Betsy’s choice of lovers. Perhaps she was headstrong and rebellious, perhaps her partner choices were dictated by an aversion to white men. I have the same feeling about Jane Austen’s novel; why are we led to admire the prudent, restrained, careful sister, whose main contribution to the plot for most of the book is to retrain herself? Betsy had different lovers, white, mulatto, and black — I really should not read more into her life than the bare facts.

But I keep writing Betsy and Jeannie stories in my head.

After 1834, the record books go blank. When the slaves were no longer a valuable commodity, no one bothered to keep accurate records of their existence. It took a generation or two for many of their descendants to adopt surnames and begin to appear as individuals on church and civil registries. So their is a gap that makes it difficult to connect these women and their children with present day families.

Betsy and Jeannie came up in research for the book I am working on. They attracted me because suddenly, out of the wall of historical noise, a little human tale appeared, ever so faint, intimate and innocent. We don’t mean to forget enslaved people, but often in our attempts to develop grand theories and apportion blame we overlook the fact that they had, well, lives. They conceived and bore children, felt joy and sorrow, suffered the deaths of loved ones, and sometimes won small victories. (That the sex was coerced is a possibility. At the very least, there would have been a power differential that cannot be ignored.)

I have just the faintest hope that in publishing this little story, I might inspire a glimmer of recognition in some family genealogist with ancestors on Grenada. I would love to know what happened to these people, where their descendants ended up.

To "They found partners, had sex, had babies, felt joy and sorrow, suffered the deaths of loved ones, and sometimes won small victories against the advance of time" I feel compelled to add "were raped." As a distinct possibility.

Fascinating as ever. Will keep eyes and ears open.