Jay Gatsby with a shotgun at Long Point

Lake Erie's Long Point and the company that saved it

Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are… F. Scott Fitzgerald “The Rich Boy”

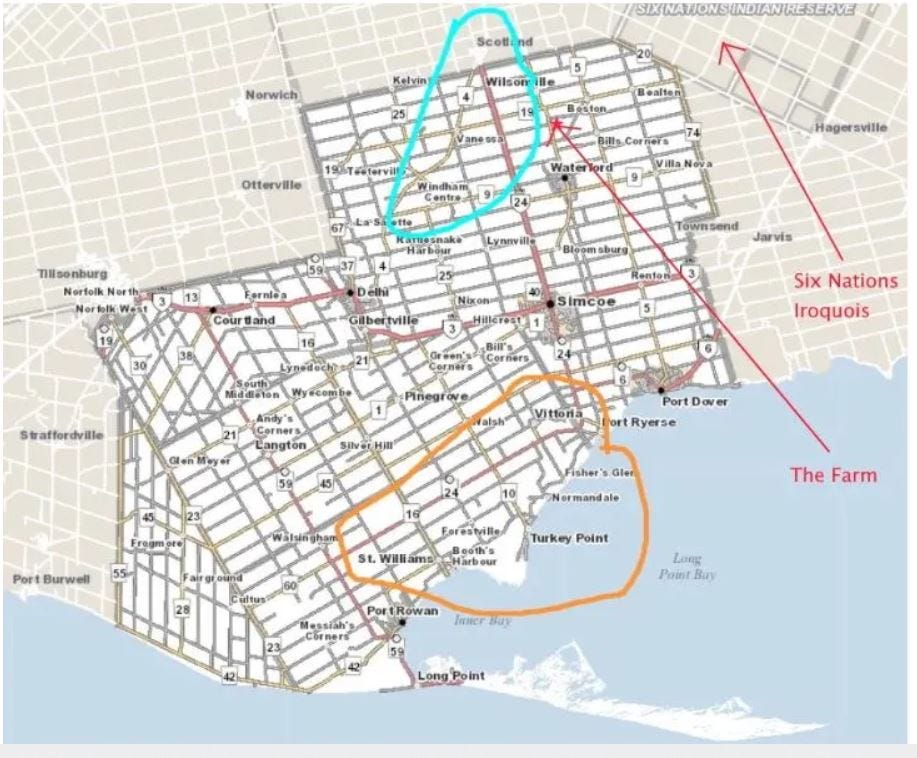

I’ve written about Long Point before,1 mostly because it is a central geographical fact figuring in the lives of many of my Norfolk County ancestors who settled along the Lake Erie shore. They have logged, hunted, and fished there; for 200 years they have gazed at its shimmering mirage-like shadow along the horizon and dreamed. Of course, they can’t log or hunt there any longer, not for more than a century, because most of the Point is owned by a private consortium of wealthy duck hunters, the Long Point Company.

Long Point is that feathery spine of sand jutting into Lake Erie from the shore of Norfolk County where I grew up. It’s a spectacularly wild and lonely place, best seen from the air where you can admire its windswept beaches and serrated marshes. It has been the scene of shipwrecks, prize fights, brothels, lynchings, and unsolved murders. Legend has it that treasure is buried there, guarded by a ghostly black dog. It’s also a unique ecosystem, a haven to migrating birds, which also makes it prime shooting country. In the 1890s, J. T. Lord, of the great merchant firm Lord and Taylor, was reputed to have shot 3,000 ducks in a single season. Such slaughter is unimaginable to me, but does remind a person how many species have disappeared, how many are down to the existential wire, and how the rich can afford to think and feel differently from you or me.

The appalling irony is that without the secretive, super-rich and their Long Point hunting club, the Point might not have been preserved as a pristine wilderness. Left to their own devices the settlers along the north shore of the lake (the public at large) reduced the towering primeval forests to acre upon acre of blowing sand. This is well known, not to be doubted. And my family had a hand in the destruction. Senator Alexander McCall, former mayor of nearby Simcoe, was a timber baron, as was his brother Daniel Abiel McCall in St. Williams, on a slightly lesser scale. Daniel Abiel was my great-great-grandfather. As the St. Williams Conservation Reserve site brutally puts it: “Within 50 years parts of Norfolk County were desert.”2

But the Point, in all its splendor, generally escaped the destruction because it was not accessible to the public. You can see it from the air or from a boat offshore, but you can’t land there. The eastern end of the Point is a federal wildlife sanctuary and at the western end there are some privately owned cottages and a provincial park. But 40% of the Point, 3,240 hectares in all between the wildlife sanctuary and the provincial park, is owned by the private Long Point Company and has been so since 1866 when a group of Canadian businessmen bought it from the federal government for $8,450. In relatively short order, the shares gravitated away from the original owners into the hands of very wealthy Americans, men who went to Groton and Yale, men with familiar names like Morgan and Whitney. Think: Jay Gatsby with a shotgun and a seaplane at the foot of Wall Street waiting to fly him to the marshes of Long Point.

Two books (I think of them as the Old and the New Testament) have supplied the basis of current knowledge about Long Point. The first is E. A. Owen’s Pioneer sketches of Long Point settlement, or, Norfolk's foundation builders and their family genealogies, published in 1898. It is our Book of the Prophets, providing an immense amount of detail about the original white settlers who received land grants between Big Creek and Port Dover after the American Revolution. Though every prominent family owned at least one copy in days gone by (we have perhaps four or five), it is not a trustworthy document. Much is left out and much that is there is legendary. Also it is about the people, not the land. And the people settled the mainland, not the Point (which is actually an island most of the time).

The second source is Harry B. Barrett’s Lore & Legends of Long Point, first published in 1977. This is a lovely book, large format, loaded with pictures, and evocative. As the cover illustration indicates, it’s a bit romantic and concentrates on the glory of the settlers, the myriad catastrophic shipwrecks, the lighthouses, and the days of rum-running across the lake to Erie, PA, and Cleveland (as my mother used to tell it, a boat would leave Port Dover with a cargo for Cuba and return the next day empty). Barrett also wrote about the Long Point Company, polishing the theme that without the Company the Point would have been clear cut and hunted to oblivion by the locals (the strange irony of this argument is that the locals tend to come off as impulsive backwoods yahoos like characters in a Cormac McCarthy novel, which is the opposite of Barrett’s intended message).

The time was ripe (has been ripe for a long time) for a critical look at the history of Long Point. By “critical,” I mean a deeply researched examination of the stories and legends involving the collection and analysis of sources. Stephen Selk’s brand new Lake Erie’s Long Point and the Company that Saved It (just out with Lulu) provides that critical perspective.

By his own count, he spent over 2000 hours researching his book. It’s a labour of love that harks back to his father’s first glimpse of the Point.

As an underprivileged kid he had the opportunity to attend a YMCA camp at Fisher’s Glen in 1932 and 1933. I know he really enjoyed that and I surmise he looked across Long Point Bay one day and said to himself, “Some day I’m going to go over to that island.”3

Eventually, Selk’s father was able to purchase a cottage on a parcel of leased land, later expropriated as part of a new provincial park. But Selk, the son, bought another cottage nearer the mainland, where he now spends vacations. Selk grew up in Toronto. In 1952, he spent a year studying with Marshall McLuhan at the University of Toronto, though he was majoring in chemical engineering. For most of his professional life he was in Washington working as a federal investigator. As seems fitting, the inspiration for his book came inside a library.

I always loved libraries, having spent endless hours perusing the University of Toronto’s vast collection when I was a student. After I retired, a few years ago I obtained a Library of Congress research card. On a lark, while there one day, I typed in Long Point and hit search. I was amazed what popped up. The library has all the local books from the region – even recent ones. And they have others. One from 1932 and it is catalogued as “socially significant” and for good reason. That started my “investigation.” What’s a retired federal investigator to do?4

Lake Erie’s Long Point and the Company that Saved It is massive, a thick, generous coffee-table book that covers the history of the Point from the formation of Lake Erie a scant 12,500 years ago (not so old after all) to the present. It includes chapters on the earliest indigenous inhabitants, white exploration, and, eventually, settlement by the United Empire Loyalists, refugees from the incipient United States. All this replete with gorgeous and sometimes rare old photographs, facsimile documents, and quotations (he managed to track down several privately published volumes by Long Point Company members, exceedingly rare and sometimes still under copyright restrictions).

From the first, the Point was preserved from the pioneering free-for-all by class and privilege. British army officers liked to hunt on the Point, and thus it was never included in the initial land grants. In 1866, the Point was put up for auction and purchased in parcels (for between 50 and 70 cents an acre) by seven individual wealthy Canadian investors who turned out to be acting together as a syndicate. They quickly filed for incorporation as the Long Point Company with a capitalization of $50,000 (a hundred shares at $500 each), a value that was totally invented at the time. Several of the founders put their shares up for sale, marketing them aggressively in the U.S. John Lord, mentioned above, a British citizen living on an estate in New Jersey, became a shareholder in 1869. In 1877, Louis Cabot of Massachusetts bought shares, followed by a who’s who of American super-wealth. By 1883, when Prince George hunted as a guest of Sir Hugh Allen (he shot 82 ducks his first day and 59 on the second), the Point had become private playground for the rich and the celebrated.

There is some irony in the book’s title, though Selk is careful not to editorialize — the Company has deep pockets and sedulously guards its privacy. Nonetheless, he manages to lay bare many of the tensions involved in such an enterprise, not the least of which is the fact that descendants of the people who settled the north shore of Lake Erie, as well as the wider public, are barred from a gloriously beautiful nature preserve on their doorstep. The rich-poor divide runs like a four-lane highway through the story. The locals acted as punters, guides, and gamekeepers, while the visitors blasted away at migrating birds. There is a chapter on “Artists and Artisans” that includes a section on the carving of decoys, which the locals raised to the level of a minor art form, at the service of the shooters out on the Point. Over the years, the Company has skillfully managed to dance away from the ever present threat of expropriation — it keeps its head down and profits from the legend that it takes care of the land better than the government could.

Selk fills the later chapters of the book with details of share transfers and tales of the rich eccentrics who came to Norfolk to shoot. This is highly entertaining material in the way all inside tales of the lives of the rich and famous are entertaining. But as you read deeper and deeper into the book, the charming local lore and the long list of eccentric characters begin to accrete a sense of foreboding and resentment. A deeper story emerges, something to do with wealth, privilege, and privatization of the wilderness. The rich are not like you or me. They can keep the pristine bits of what's left of the world to themselves.

Several members of the Long Point Company were also members of other hunting and fishing clubs, little metaphorical (and sometimes literal) island sporting enclaves preserved from the locals and largely from government interference. Examples Selk writes about include the exclusive Jekyll Island Club located on an Atlantic barrier island on the coast of Georgia with a beach along the ocean side and inland-facing marshes where the duck-hunting took place. The club was founded in 1886. Another is the collection of three salmon-fishing clubs — the Ristigouche (sic) Salmon Club, Camp Harmony, and Kedgwick Lodge on 26 miles of the Restigouche River in New Brunswick. The first rough building at Camp Harmony went up in 1885, replaced in 1895 by a stately lodge built by Stanford White. In each of these places a similar culture thrived comprised of new rich, eccentric locals and guides, rustic art, and massive kills.

This practice of snapping up chunks of wilderness and preserving them exclusively for the wealthy has taken a new twist nowadays as the gap between the super-rich and the rest of us expands. Hardly a week goes by that I don’t notice a story about venture capitalists and Hollywood celebrities buying up huge tracts of Montana5 and conflicting over access to the locals. Or rewilding schemes in Scotland (meaning ordinary people stay out). Anders Holch Povlsen6, a Danish entrepeneur, is now the largest private landowner in the Highlands. Rewilding, preserving, etc. are becoming watchwords for exclusivity and wealth. But the question remains whether or not the preservation of nature by and for the wealthy is a higher value than giving access to people in general to what’s left of the world’s natural beauty.

Stephen Selk does not, as I say, engage in this debate. He only lays out the facts. The last 60 or so pages of his book consists of biographies of Long Point Company members with the sources of their wealth, long lists of companies and board memberships, on the face of it a bit dry yet immensely powerful as an aggregate. And you mentally contrast this with the anecdote about Selk’s father, the little boy at the YMCA camp for poor city children at Fisher’s Glen, gazing across the bay at the shimmering dream of Long Point.

Long Point: A Geography of the Soul

This is a text I originally posted on my magazine site Numéro Cinq. It has more context here at Out & Back and might therefore find a better audience. Or not. I have, for example, published here some of the essays and stories I wrote based on Norfolk County and St. Williams sto…

From an email Stephen wrote to me.

From an email.