Reading the runes (kind of a pun)

On the advice of Angus Martin, who until last June was the executive director of the Grenada National Museum (indeed, his name is still listed as such on the museum’s web site), I took a day to visit the Dunfermline Estate ruins, now abandoned, and River Antoine Rum Distillery, still in production and very much a tourist attraction, to give me a better sense of the grammar of a sugar estate. Even now, three months after my trip to Grenada, I am still learning to read the runes of the plantation landscapes. In September, I didn’t know what I was seeing or even what I was looking for, but it’s amazing what my photographs reveal after the fact.

Plantation ruins have a structure I am beginning to recognize. I had read the books and pored over historic drawings and paintings, but there is nothing like actually standing amidst the crumbling walls and rusting machines to render the patterns visible. I know now to look for markers, read the system.

Sugar estates were large farms, very profitable due to the free labor supplied by enslaved people. The works were the focus for large spreads of fields, gardens, pastures, and woodland that fed the system. The landscape of Grenada today is often overgrown with bush and tree orchards gone more or less wild; in earlier times, more of the land was cultivated, with dirt paths and laneways skirting the fields and connecting them to the processing plant. When I was exploring Mount Rich, I found many of these old pathways still in existence. They wound uphill from the plantation ruins by the contemporary cricket ground. In places, the trees opened up to reveal a field under cultivation, freshly cared for and irrigated. But much of what I saw was overgrown cocoa orchards.

In terms of large categories, the sugar system is much like other farms. You grow the product and then you add value with some post-harvest processing before selling it on. I grew up with a similar process on our tobacco farm in Ontario: grow the tobacco, dry the leaves in oil (wood in the old days, now gas) fired kilns, store them in the pack barn, then steam them (to soften the leaves), grade them, and pack them in bales for shipment to auction barns. The infrastructure consisted of fields, drying kilns, pack barn (for storage), and a steam room and grading room (in one corner of the pack barn). Also a greenhouse for growing tobacco seedlings before planting, a driveshed for machinery (tractors, planters, harvesters, sprayers, various bit of cultivating equipment, irrigation pipes and pump), a sharegrower’s house, and a tenant house for a hired man. Early on we still used horses during harvest. Thus we also needed a stable and a pasture. We also excavated an irrigation pond to supply water.

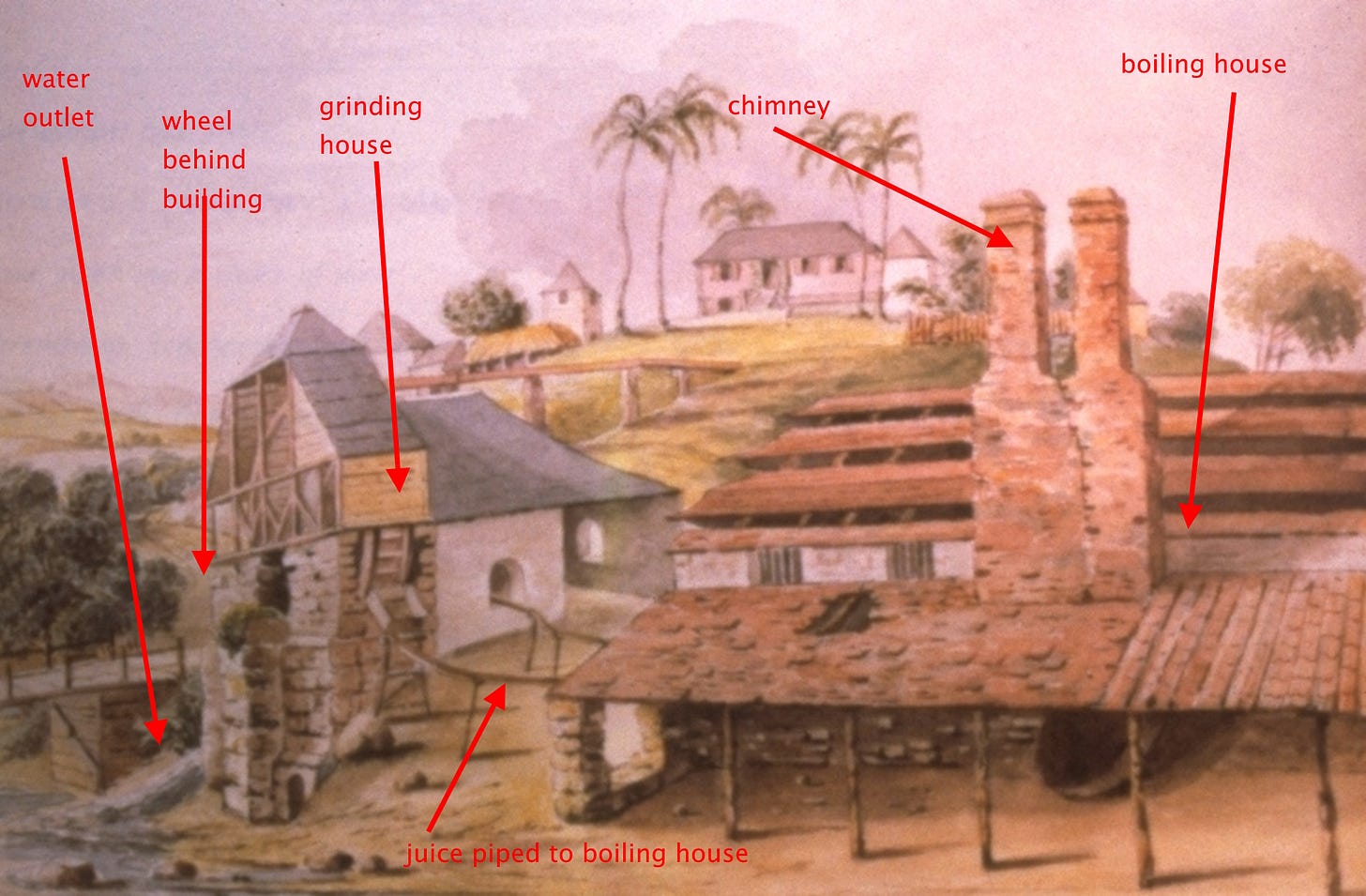

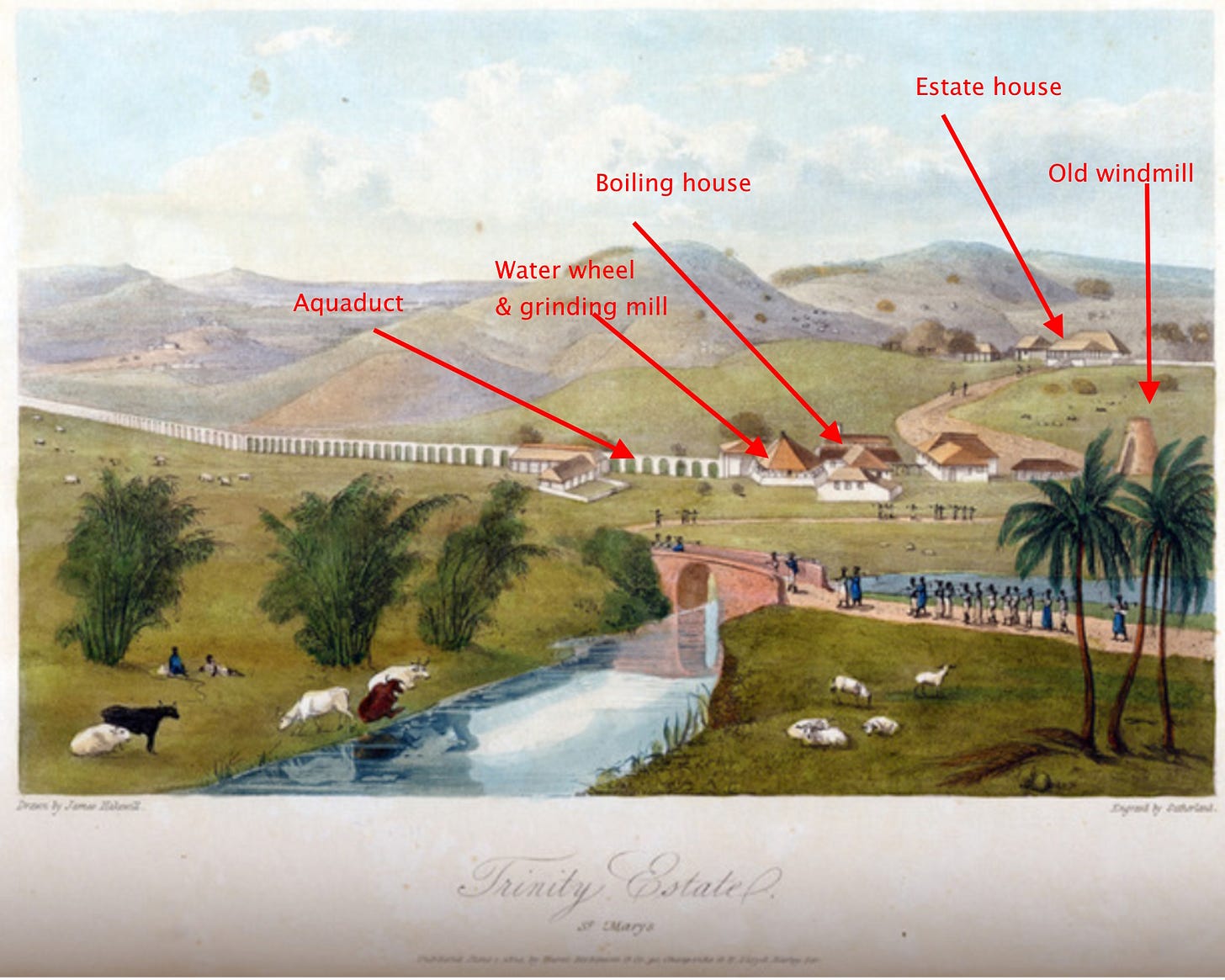

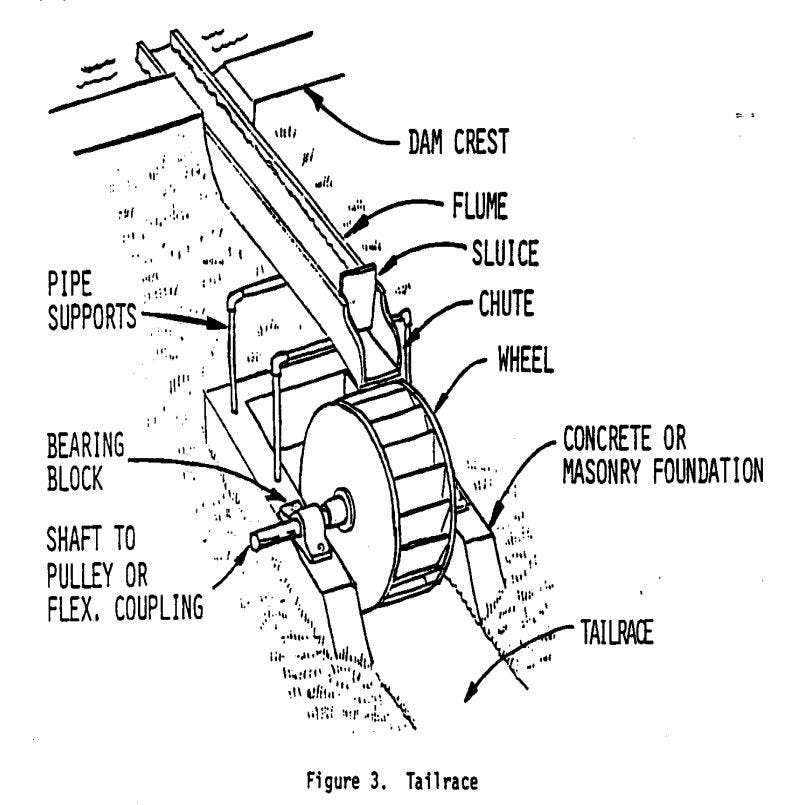

Cane is just a tall grass, very sweet to chew (which the enslaved people often did surreptitiously, as a supplement to their normal diet — it was commonly known that the mood, energy, and health of the plantation population improved during harvest, despite the hard work). Before it becomes white table sugar, it has to go through a series of post-production refinements starting at the plantation. The basic sugar estate post-production infrastructure consisted of a crushing mill, a boiling house, and often a rum distillery. The crushing mill was a machine with heavy iron rollers to squeeze juice out of the cane stalks. The power required to turn the rollers came from a water wheel or sometimes a windmill or even a mill turned by cattle (oxen). The crushed cane juice ran through pipes to a boiling house where it was boiled in a sequence of open pans stirred by attendants, reducing the amount of liquid and allowing the sugar to crystallize. The crystallized sugar was separated from the remaining liquid and packed into wooden hogsheads for shipment to Britain (where it was refined again into white table sugar). The liquid left over from the boiling was molasses, which, early on, was sometimes fed to the enslaved people. But then the planters learned how to make rum out of molasses in pot stills and a second profitable industry developed.

For the most part, the plantation buildings or works were built of stone with wooden superstructures. The parts made of wood have disappeared, including the thatched hut villages where the enslaved people lived, the yards, as they were called. The whereabouts of these yards and their graveyards remains a haunting mystery at most of the ruined plantations. Archaeology could help fill in the blanks, but motivation and money seem to be lacking. I do know from reading documents that the yard at Mount Rich was located where the cricket ground is today. Of course, nothing remains of those buildings. Many planters set aside “provision grounds,” garden plots where the enslaved people could grow their own food. There would also be barns and pens for cattle, chickens, hogs, goats, and horses, as well as machine sheds and workshops for joinery, masonry, cooperage, furniture, wagon production, smithing, etc.

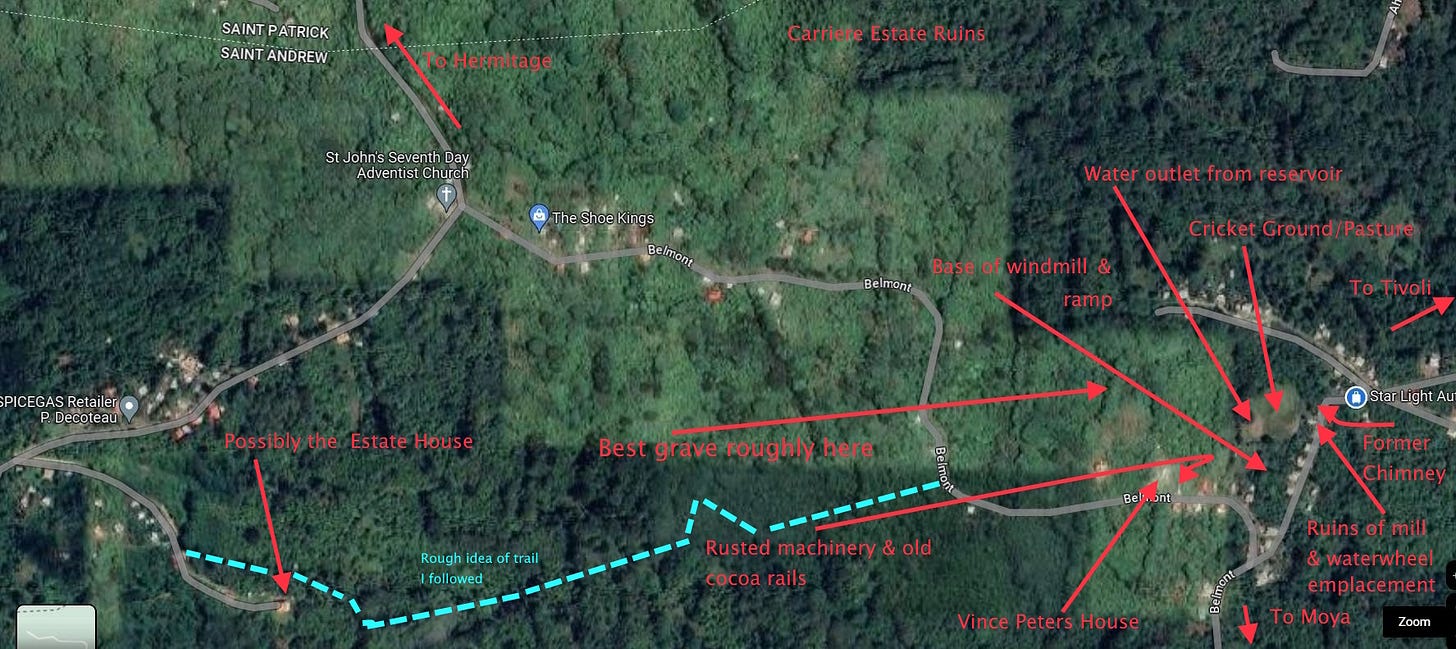

So when you find a set of ruins you start to figure out the layout based on these key bits of infrastructure. When I first visited the estates at Carriere and Mount Rich, I had only vaguest notion of what I was looking for. In fact, I expected to find nothing. These are not well known tourist destinations. A bit of wall, a stone piled on a stone would have been remarkable even if I didn’t know what it was. But now looking back I can see how this bit of rock wall related to that pile of rocks over there, and I can imagine the bustle of the gangs of workers and their overseers (mostly enslaved themselves, as I say).

Dunfermline

On the third day of my stay on Grenada, I walked to the Dunfermline Estate, which is said to have some of the best preserved ruins on the island. It wasn’t far from where I was staying opposite Ben Jones Drive in Moya to Dunfermline. But as usual — pleasant little adventures along the way. Two men in a yard by the road, one up a ladder in a tree, the other beneath. “What’s going on?” I asked. “Breadfruit,” he said (though in the nature of most of my communications in Grenada, he had to say this five times before I understood). A large green orb thunked to the ground. I had never really looked at a breadfruit before. We chatted. Another came down. He picked it up and handed it to me. Beads of juice dripped from its sides like sweat. Did I want to take one with me? he asked, reminding me how kind and generous people are in Grenada.

Dunfermline looks abandoned, derelict. There is no one to watch the place. At first, I was disappointed. It looked like a piles of rubble with a couple of buildings still standing, though they looked empty and forlorn. But then I started picking out the details. The water wheel is still in place, amazingly enough. The remnants of the crushing machinery stand next to it, the actual mill house gone, just rusting cogs and rollers. I took a lot of pictures and only now, after working with the photos, zooming in, cropping, and brightening them, can I see what I saw clearly, concealed in the bush behind the wheel, a beautiful stretch of wall that dammed a reservoir and a stretch of masonry aqueduct running from the reservoir to the wheel.

A few yards away loomed the boiling house, with its tall chimney, now almost hidden in trees that have grown up. It was stunning to push open shattered door and step inside what was something like a dilapidated cathedral or an airplane hanger (take your pick). The walls were broken, in places the stone replaced with concrete blocks. Light filtered through the gaps and broken windows. But down one wall were the boiling troughs, a series of circular depressions which once contained the “coppers” where the juice was reduced. These depressions decrease in size. Along the opposite wall a series of rectangular emplacements for the reducing pans, where the crystallizing sugar went after the series of coppers. I had seen paintings and drawings of just this building on other islands or at other times, the steam billowing up to the rafters, workers with long spoon-like ladles stirring the coppers, skimming the sugar scum from the top to the next and smaller copper.

It’s an assembly line, at the end of which you have casks of brown sugar and liquid molasses separate. Often, the molasses was further processed into rum, much more valuable and easier to transport. There was another large building next to the boiling house at Dunfermline, but it was full of bats and the floor was flooded. I could not explore the layout or figure out exactly what it was used for. I am guessing it may have been a distillery or something to do with downstream sugar refining of another sort.

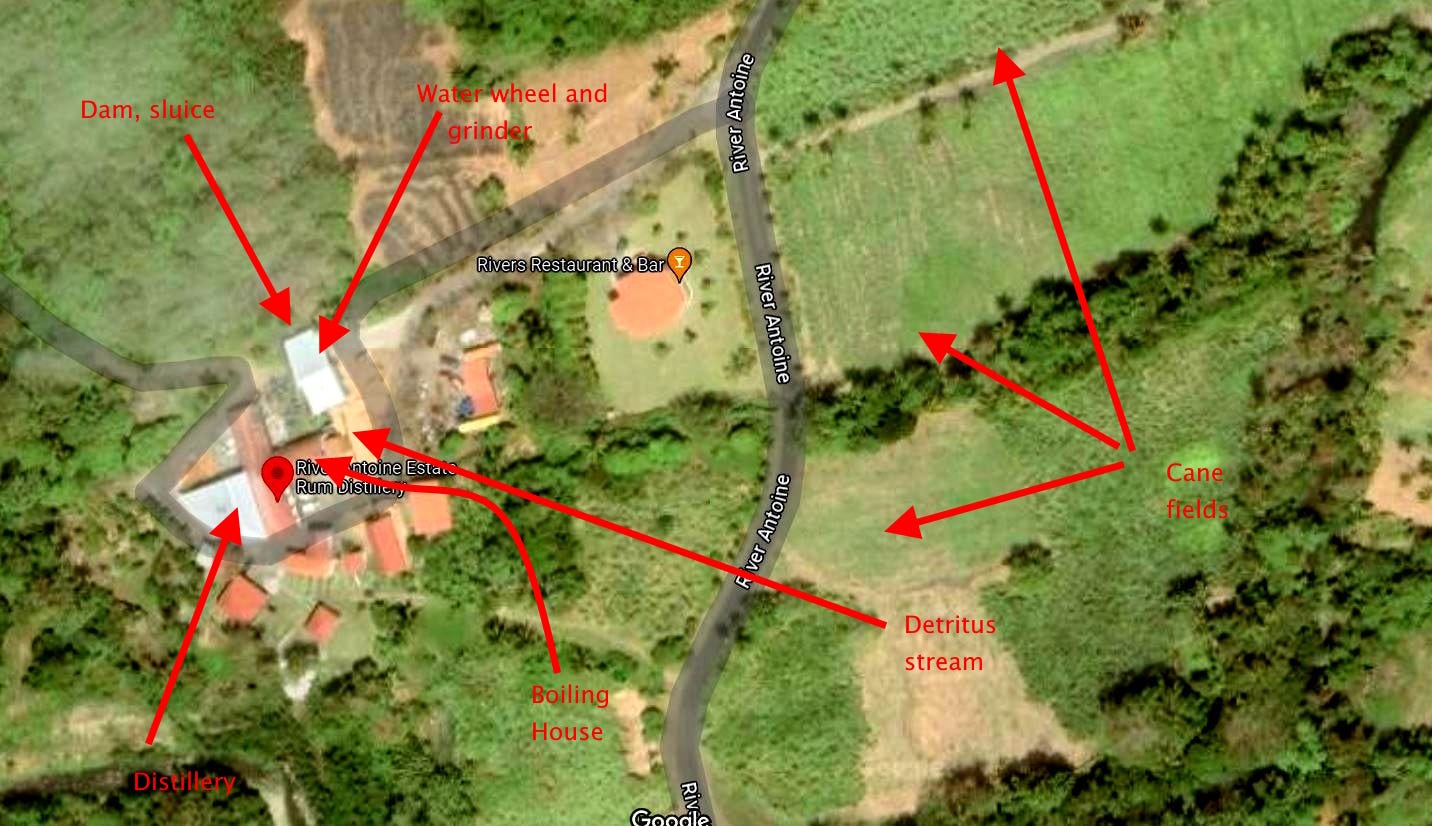

River Antoine Rum Distillery

Then, for comparison’s sake, I took a bus to La Poterie (pronounced something like “poetry”) and then walked to the River Antoine Rum Distillery where sugar cane is still being grown and processed today. The signage was unhelpful and the large restaurant by the road was closed, so naturally I missed the turn up the lane to the works and ended up at the River Antoine beach, totally empty except for a small family by a parked car about a quarter of a mile away. I thought I might swim, but then I remembered how in Merle Collins’s novel The Colour of Forgetting people were being swept away by the undertow or perhaps water demons. I was a bit tired and alone and not in the mood for encountering water demons. It was startlingly beautiful though, and strange, strange because humans generally find a beach like that ripe for commercial exploitation. Where was the usual line of multi-story hotels? I wondered.

The contemporary crushing mill-boiling house-distillery complex is easy to see, one building flowing into the next, the fields of sugar cane stretching toward the beach where the Atlantic rollers landed. A dam and waterwheel power the crushing rollers, which are outside under a canopy. A lengthy conveyor belt carries the crushed cane detritus away from mill. Huge piles of shredded cane lie yellowing at the edge of the building complex.

A pipe runs from the crusher into the boiling house, which was closed when I visited. Then next to the boiling house was a distillery, the huge pot stills also out in the open, two men making repairs while I watched, piles of scrap wood and lumber next to the boilers. Then ancillary buildings, storage spaces with stacked wooden casks, office space, and so on.

Carriere & Mount Rich

As I say, there is a huge difference between what I saw in September and what I see now in photos and in my mind’s eye. I read the landscape better.

One is not likely to find a waterwheel in most places, but I can now recognize the foundations where the wheel once sat. Here is the wheel foundation at Carriere. The crushing mill would have been on the left in a building repurposed as a joinery shop. Filled in with trash and rubble, it was at first every difficult for me to imagine what it once might have looked like.

And the dam and reservoir and aqueduct were equally hard to discern. I saw a pile of rocks, some cut and shaped, and a ruined arch, but the rest of the waterway had disappeared when the ground was leveled for a cricket ground. I could also make a length of suspiciously symmetrical hillside that must have been manmade (now that I think about it). At first, I walked all along this feature without realizing what it was.

And here is what I think was the waterwheel foundation at Mount Rich. I couldn’t find a reservoir, but on an 1869 plan a canal runs right to this spot. Another time I will go back and try to trace the canal and find its source.

When I took the picture, I really didn’t have a theory about what this was, just a mysteriously narrow shaft between two walls. And it was difficult to get a decent shot because the area was so entangled with vines and bushes. It only grew on me over time that this might be where the waterwheel was. There is nothing left of the canal itself except a filled in ditch depression aligned with the wheel foundation. I would need to go back and look again to try to identify the boiling house, which must have been quite near the waterwheel. When I visited in September, as I say, I was a neophyte, looking but not seeing.

Dunfermline, Carriere, and Mount Rich all had foundations and bits of ironwork that I could identify as part of a cocoa operation as well. Cocoa was always produced on the island but became more prevalent as sugar declined in the 19th century. Much of the surrounding landscape at Mount Rich and Carriere was overgrown cocoa orchards, still harvested but no longer pruned or otherwise maintained. At least that is how it seemed to me.

Why I obsess on small things

This all might seem tedious. Why am I going on about piles of rock and twisted masses of rusted machinery? It’s mostly because I want to understand slavery beyond the abstract concept, the statistics, and the horrific stories. It’s awfully easy to condemn history and feel good about oneself. I want to take a step into that distant past and try to see the enslaved people as people. Pretty preposterous for a white guy living in Vermont. But still I ask, because it interests me, what did they do with their days?

One very common mistake is to imagine all enslaved people as either field hands or house servants. In fact, the trained sugar makers including boilers and distillers were slaves. And many more were highly skilled tradesmen, coopers, carpenters, masons, cooks, nurses, midwives, and seamstresses. Others would become specialists in animal husbandry and dairy management. Others still had places in what you might call middle management such as gang leaders, drivers, and overseers. At Mount Rich, six men were for years rented out as soldiers and slave hunters to the Colony Rangers. In other words, the plantation had the air of a small village of that era with all the occupations represented, and almost the entire population was black, either African or descended from Africans, with a few mixed-race individuals.

It is difficult for us today to imagine what it might have been like to live at Mount Rich or Carriere in, say, 1820. But by understanding the landscape, the system of the plantation buildings and the sorts of work that took place inside them, I am trying to better imagine just how the people moved through that landscape, the shape of their lives.

We have a tendency to generalize from horrific examples of brutal plantation owners, or we like to think that all enslaved people were actively plotting rebellion and constantly sabotaging the works. But if we try to correct our vision back toward the center, we might arrive at a somewhat more nuanced and plausible idea of slave life.

Be clear: I am not taking the Ron DeSantis line that slavery was good for slaves and prepared them to take productive roles in modern life. This is a repulsive idea. Horrific things occurred; the threat of random violence, sexual abuse, and forced removal and family separation hung over everyone, without any legal recourse. I have studied the Slave Registries from which it’s easy to see that diseases of malnutrition were endemic. Yet within the terrible constraints of chattel slavery, these people found ways to live meaningful lives, raise families, advance themselves by learning skills or by marketing produce from their gardens, engaging in religious and cultural activities, some remembered from Africa, some hybridized from their colonial experiences. The daily heroism of an enslaved person is something we often overlook. It’s something I thought about often as I wandered amid the ruins.

If you think about it, Grenada today, especially away from the cities and tourist areas, feels like this. It’s a religious, somewhat conservative culture. The people are decent, kindly, and entrepreneurial on a small scale. Families cook and sell food along the roadside where there are frequent makeshift bars, corner stores, and bakeries. There is always music blaring from this or that bar. Since the 1950s much of the land has been split up into small holdings reminiscent of the provision grounds. Many people I talked to owned patches of ground out in the woods where they gardened. Grenadians seem fanatical about their gardens. The lone man in rubber boots with a cutlass in his hand and a sack over his shoulder was a common sight once I got off the roads into the woods.

That’s why I puzzle over these ruins, that sense of the continuity of things, people, sentiments, human relations.

Imagined people, whisps of memory, objects once handled by slaves, presences crowding in.

So interesting!!

Loved reading this Grenada writing, Douglas. The images remind me of the plantation museum on St. Croix, which was the first Caribbean island to abolish slavery following a revolt against the Dutch (now one of the US Virgin Islands). Dirty, dirty sugar...