Much of my misguided youth was spent studying philosophy. I ended up doing an M. Litt. at the University of Edinburgh (dissertation on Kant’s ethics1) and teaching philosophy for a year at the University of New Brunswick before abandoning academia to become a newspaper man. At the time, I called this “throwing myself into the eschatalogical matrix.”

I never left philosophy behind. It seeped back into my mind via literary criticism and even the discussion of narrative craft (Russian Formalism and Structuralism). I kept mulling things over and making notes, searching for a system, the system that would organize all these competing ideas in my mind, not as a scholarly endeavour, but as a personal inquiry. Then two things happened to focus my thoughts. First, my son Jacob went off to the University of King’s College in Halifax, spending the 2009-10 academic year in their extraordinary Foundation Year Program, essentially a Great Books and Humanities reading year. My parting paternal advice, when I dropped him off at his dorm that September afternoon, was encapsulated in a scribbled diagram of the two-world structure of Western thought, which he pinned to his wall. All that year, we burned up the phone lines, talking about books and ideas. It was exciting and revelatory. Second, I was reading my way through Witold Gombrowicz’s fiction and diaries only to discover that he had also written a handy little history of Western philosophy called A Guide to Philosophy in Six Hours and Fifteen Minutes. Actually, he didn’t write it; he spoke it (there are gaps here and there in the transcription).

That six hours and fifteen minute time span triggered a competitive reaction in my head. I had a lecture to deliver at the college where I taught at the time (2010), and my head was full of my conversations with Jacob, and I thought, well, why not just try to beat Witold’s time and boil it all down to 50 minutes? (I gave the lecture very fast.) Then I took my speaking notes and wrote them up as an essay, which The Brooklyn Rail published (here). Amazingly, the Rail included a slew of diagrams and inset text boxes I insisted on adding to the original (the web version does not present the graphics and insets nearly as well as the hard copy version, unfortunately).

Then dissatisfaction set in, mostly because Jacob wasn’t impressed. He had moved beyond me. He really didn’t say much (he mentioned that I might have misrepresented some arguments in The Republic), but you know how it is when a child condemns you with silence. I took this to mean that he thought I was perhaps a bit slick and superficial. He was studying Greek and reading Plato in the original. But mostly these intuitions echoed my own doubts. I had meant to include the essay in my book The Erotics of Restraint, but John Metcalf, the editor, sent it back with notes and queries, lots of circled bits where I had lost him. There was nothing there I could solve with a quick rewrite, so I took the essay out of the book and began to recast it from the beginning. This entailed much reading and rereading (more lengthy phone calls with Jacob).

What I am publishing here is the rewritten Mappa Mundi, map of the world. I’ve included the original diagrams, but Substack doesn’t do text boxes or sidebars well, so those are included as footnotes. They don’t quite work as footnotes. They were meant as counterpoints and extra-commentary and examples. They were supposed to be beside the text, not inserted after a word as footnote are. Read them in this spirit.

I am not sure anyone will want to read this essay, but, to me, this is the job done (until the next time dissatisfaction sets in). The early stuff about the pre-Socratics and, especially, Anaximander is newly added. I’ve rewritten all the Plato material, and Kant, too, is redone. The tone and attitude (a bit too cynical and dismissive in the first version) have been adjusted. The whole thing is clearer, I hope. It makes perfect sense to me.

Also Substack informs me that the essay is too long to go out as a newsletter, so email readers will get a portion of the whole thing but will have to click on the header and go to the web version to read it all.

Mappa Mundi: The Structure of Western Thought

The woods of Arcady are dead,

And over is their antique joy;

Of old the world on dreaming fed;

Grey Truth is now her painted toy;

– W. B. Yeats

695. Prophecies. – Great Pan is dead.

–Blaise Pascal Pensées

1 - Meeting the Other

In the third chapter of Exodus, Moses is herding his father-in-law’s sheep on a hillside when the Lord erupts in a sheet of flame from a nearby bush. The author presents the scene as a scientific impossibility: the bush burns furiously without actually burning up. The voice from the bush adjures Moses to take off his shoes because the ground on which he stands is holy. Then Moses turns his face away in terror. In the King James Version, the scene reads like this:

Now Moses kept the flock of Jethro his father in law, the priest of Midian: and he led the flock to the backside of the desert, and came to the mountain of God, even to Horeb.

And the angel of the LORD appeared unto him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush: and he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed.

And Moses said, I will now turn aside, and see this great sight, why the bush is not burnt.

And when the LORD saw that he turned aside to see, God called unto him out of the midst of the bush, and said, Moses, Moses. And he said, Here am I.

And he said, Draw not nigh hither: put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.

Moreover he said, I am the God of thy father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. And Moses hid his face; for he was afraid to look upon God.

But the narrative itself, the reassuring cadence of the words, the logical throw of subject and predicate, veils the heart of the encounter. What Moses finds so terrifying is the absolute difference between his human self and the infinite Other. Everything about the scene puts Moses and his world in doubt. Every expectation, every frame of reference, every category of thought meets its antithesis and explodes. This is matter meeting anti-matter. Yet Exodus does what human discourse has always done, which is render the implacably different symbolically. God speaks with a voice that seems, to Moses, recognizably human. Out of the fire comes something familiar.

We are used to speaking fashionably of “difference,” but I want here to insist on the utter and terrifying difference of difference.2 We have literary equivalents in which a brush with absolute otherness–God, Being, the Real–renders the subject, from the common perspective, insane. For example, there is Kurtz’s “horror” in “Heart of Darkness,” which Conrad describes as the effect of exposure to the wilderness, a common motif in the presentation of difference (see, obviously, the Old Testament, where the Wilderness is the scene of God meeting man). “But his soul was mad,” writes Conrad. “Being alone in the wilderness, it had looked within itself, and, by heavens! I tell you, it had gone mad.” In E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, Mrs. Moore enters the Marabar Cave, encounters darkness, the anonymous pilgrim mob, the smell, the mysterious echo and suffers a psychic break.

She lost Aziz in the dark, didn’t know who touched her, couldn’t breathe, and some vile naked thing struck her face and settled on her mouth like a pad. She tried to regain the entrance tunnel, but an influx of villagers swept her back. She hit her head. For an instant she went mad, hitting and gasping like a fanatic. For not only did the crush and stench alarm her; there was also a terrifying echo.

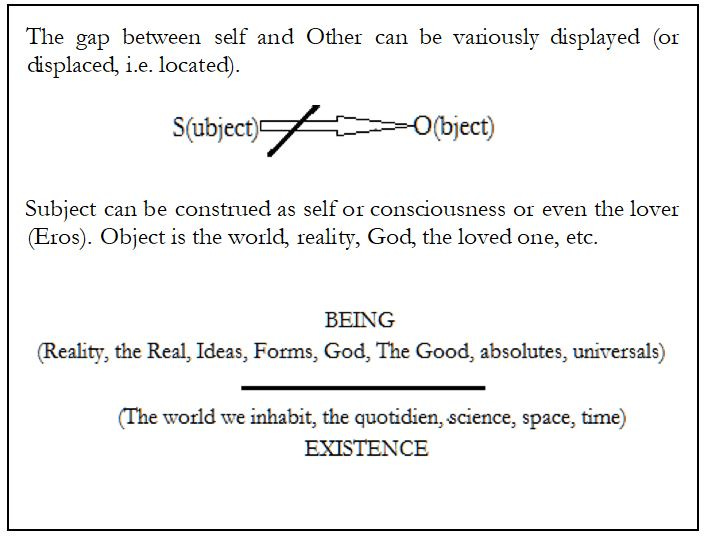

Such examples characterize a meeting with something, not a benign and loving God, but an alien, indifferent, and undifferentiated otherness, a word that better captures the unspeakably primordial and trenchant meaning of the encounter. Humans seem haunted by the idea that existence is fundamentally split, a split that has been variously and not exhaustively characterized by phrases such as human and divine, I and thou, self and other, subject and object, particular and universal, finite and infinite, temporal and eternal, existence and Being, sensible and intelligible (Plato), phenomenal and noumenal (Immanuel Kant’s terminology), appearance and reality, quality and essence, civilization and wilderness. These antonym pairs amount to the same figurative cleavage, the abyss between the thinking self and something else that, because it is different and other, is fundamentally unknowable (or hidden as Heidegger said, or repressed as Freud said). Because its face is veiled, because it presents itself only to us as infinitely inscrutable, it seems to incarnate an endless negativity that cancels even our humanity.3

Plato was at least partly right when he said that we can only know what we know already, that knowledge works by identity. What we cannot know, cannot access, we also cannot experience, and yet this unknowable is all around us, lies inscrutable and threatening behind everything we do know, crouches even within our hearts in a place Freud called the Unconscious. Mostly we cannot escape the feeling that it is watching us, waiting to trip us, or sometimes bless us. At the end of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Wittgenstein threw up his hands and wrote that we must remain silent about the things whereof we cannot speak, by which he meant a long list of absolutes including God, the Good, Beauty, etc. But that sort of conscientious self-restraint (a refusal to make leaps) has never stopped humans whose imagination is prolific in inventing dream meetings with the Other. The history of our philosophies has been a history of such dreams.4

2 - The Other in Oral Cultures

The dreams begin in the primordial time before history, the time of myth and epic, in the world of oral discourse, which in some places still hangs on in the form of melancholy tribal remnants hiding away in the deep forests here and there around the globe. We don’t really know precisely what the ancient peoples thought; we can only surmise by extrapolating backward from these historical remnants, the stories of conquered peoples, orals texts that were written down soon after the invention of writing, and from the minute amounts of art that have survived.

Oral cultures are living mnemonic devices5 with a social structure that replicates the human conception of the world at large. Villages are divided (into moieties) and the halves divided into clans, the two halves having often some theoretical antipathy mostly based on a consciousness of difference (even though, from the outside, they may not look different at all). The clans often link to a totem, plant or animal or weather phenomenon. Certain sorts of knowledge and social capacity reside with different clans, genders, or cultic groupings. Knowledge is passed down ritually and dramatically by a combination of rote memorization and rites of passage (there is nothing like getting circumcised while learning a new story to make you remember it) that reinforce the lessons and repeat the ancient myths. Myths often speak of twins or cosmic battles between elemental beings and these cosmic battles result in the creation of the world and humans.6

From the start, humans imagine the world as fundamentally riven, violent and paradoxical.7 But this ancient world of myth is far more conceptually permeable than the world we inhabit today.8 The Other is familiarized, the world of the Other populated with creatures much like those in the human world only more powerful and anarchic. Humans and gods travel back and forth between worlds. Shamans climb the Tree of Life and Death and bring back knowledge from the Land of the Gods (or the Land of the Dead if you go the other way). They assume the shape of animals; they acquire powers from totemic spirit guides. They hunt by dreams and divination. Humans can even fly and be in two places at once (defying laws of logic). To be sure, the journey to the world of the Other, as the journey to the Land of the Dead, is strange, terrifying and dangerous, but it can be accomplished.

Much of the art of oral cultures seems bound up with the idea of permeability or, in its active form, therianthropy, the ability of humans to transform into animals.9 Thus some of the earliest representational art we have discovered depicts animal-human hybrids, or creatures in the moment of transformation. For example, the celebrated shaman figure painted on the walls of the Trois Frères cave with its human legs and feet and upright stance and antlers and tail. And the Lion Man/Woman figurine found in the cave at Hohlenstein-Stadel in Germany and dating back 30,000 years ago. Which, yes, reminds one instantly of a gorgeous little panther man figurine carved by the now extinct Calusa Indians of Florida in the Smithsonian Institution. One could list any number of such objects.

I don’t wish to romanticize this moment nor endorse any New Age impulse to wax nostalgic about an imaginary Arcadian past when we were one with Nature. It’s important to remember that culture is culture, that all cultures alienate humans from the world of Nature, from the Other imagined as Nature, and from one another in some peculiarly essential way. The fundamental split comes with language, the technology by which we symbolize our sense of the world. After that, everything is interpretation and translation. And we can’t go back. Yet it remains true that within a culture, certain philosophical analogies (in this case, two worlds connected by precarious pathways over which humans may pass) stick and form a general thought framework more or less assumed by the people living in that culture. Culture tends toward the conservative unless forced to change by an alteration in circumstances (technological innovation or an Ice Age, for example) or by confrontation with an alien culture.

3 - Philosophy Begins in the Age of Literacy

The invention of writing10 was one such decisive innovation. Writing does not, as in the case of language, create a new system of symbolization. Rather, it creates storage space for memories outside the human brain (think: hard drives). Written documents are databases that can be shared. Writing vastly increases the human ability to accumulate knowledge, but it also destroyed the old oral way of life. It did this by disrupting the socially-organized dissemination of knowledge (ancient wisdom, myth) and by confronting the archaic theory of truth (truth based on authority, upon the wisdom of the elders, communal truth) with a more modern theory of truth (truth based on documentary comparison and the accumulation of facts). There is no more dramatic account of the early cultural wars between the oral and the literate than in the Old Testament, which in one aspect, at least, is the story of the battle between the people of the book, the Hebrews, and the ancient pluralistic beliefs of the Canaanites.

Within a few years of the advent of alphabetic writing among the Greeks, literate people begin to record the myths and oral epics. In about 700 BC Hesiod writes his Theogony, in which the world comes into being out of a primeval emptiness called Chaos. From Chaos emerges Gaia, Mother Earth, then Tartarus, the underworld, and Eros, followed by a handful of first generation deities. Earth and Sky procreate, and their turbulent children begin to populate the cosmos. The myth is an origin story, an answer to the questions how did the world we live in come to be, why do things happen the way they do. Philosophy as we think of it begins less than a century after Hesiod when inquiring minds try to answer these questions using concepts instead of god-stories.

Anaximander, the first philosopher to write a book (now lost), is especially notable for positing an infinite, indefinite substrate called apeiron out of which individual things emerge into existence in the sensory world. You can’t get something from nothing, the logic goes, so there must be a basic material that we can’t see but that can take the form of things we can see. After persisting a while (the German 20th century philosopher Martin Heidegger actually calls it “whiling”), these things mysteriously revert into the indefinite. The German word for this sort of underlying material is wonderful, Urstoff. By way of analogy, think of Play-doh, the modeling clay children reuse over and over to make figures. It has no qualities or divisions and so cannot be described in words. Instead of the gaping emptiness of Chaos and the heroic couplings of Gaia and Uranus, not to mention their murderous offspring, we now have a syllogism and a concept, apeiron.

This looks like a killer argument, destined to obliterate the entire magical apparatus of legend, myth, gods, divine messengers, oracles, ritual offerings, priests, and shamans—the theriophanic human/animal face of the Other replaced by the infinite indefinite, but it isn’t. Instead, philosophy only establishes a competing discourse, an alternative account of how the world and its occupants come to be based on the assumption that what exists is ultimately comprehensible (or explicable) by the human mind without recourse to magic and myth. Philosophy has tended toward the atheistical without, as has always been the case, being able to convince anyone who really wanted to believe in gods, the two discourses marching down through history together in uneasy, sometimes violent, sometimes amiable, colloquy.

But in distinguishing between an indefinite substrate and things that temporarily emerge from it, Anaximander conserved the ancient (oral) asymmetric dualism between the world of the immortal gods, Land of the Dead, etc. and the world of the merely human. The content of the relationship has altered—there are no divinities, no magical beings, and no epic narratives, but the structural arrangement (ratio) of the eternal originary cosmic material and the world of temporary existence is the same. Because what emerges into existence and then submerges again is only temporary, uncertain and fleeting, it is thought of as somehow subordinate, even inferior to the underlying stuff. This is the root of the distinction between Being (usually spelled with a capital B) and beings (things that exist in the sensory world), between Being and becoming or Being and existence, although these terms are modern and were not used in Anaximander’s day. Being is the substrate, always there, everywhere. Hypokeimenon is another lovely Greek word for this. It is real in a sense that temporary existence is not—an observation that begs the question why humans have a bias toward permanence.

This asymmetry, the underestimation of the here and now in contrast to the super-reality of the eternal unseen Urstoff becomes the obsessional core of Western thought. It provokes three largish and interrelated questions, the bones over which philosophers have been chewing ever since. One is metaphysical, theological, and conservative. What happens to divinity? Where does one place the gods, goddesses, and the myths, all the traditional cultural lore and belief? All the ancient, comforting narratives that locate humans in the cosmos? The second question has to do with the nature of language. If something is indefinite and eternal, how can one say anything about it (aside from, yes, its being indefinite and eternal)? And the third question is logical. If beings emerge from Being (apeiron) into concrete particularity only to submerge once more; well, how can that happen? How can something be both infinite and finite, eternal and temporal, universal and particular? Where people used happily to transform into animals or fall into trances and climb the Tree of Life and Death to consult the gods, receive mysterious divine messengers, or sacrifice each other to win favour, we now have an unbridgeable gulf with something that may or may not be cosmic Play-Doh on the other side. This image is rife with comedy and elemental horror, less familiar than the God speaking out of the burning bush, more akin to the booming emptiness of the Marabar Cave—dismal, suffocating, inert, indifferent, impersonal, and hopeless.

4 – After Anaximander, Retrenchment

As I say, Anaximander’s book has disappeared, and we have only stray reports of what he wrote and one enigmatic fragment of text. But it’s useful to keep his idea of an infinite, unindividuated, underlying stuff, apeiron, in mind as we proceed. It remains a philosophical problem, a mystery, and a blank page on which everyone gets to write.

After Anaximander, philosophy diverges in various directions, but the main branches belong to Heraclitus and Parmenides. Think of them as the extreme wings, each plumping for one leg of the metaphysical dualism (Being and beings). Heraclitus has no patience with this idea of an underlying infinite indefinite. He focuses on the logical problem of becoming—how can something be both infinite and indefinite and at the same time concrete, finite, and temporary? How does apeiron become my iPhone? He decides there is no underlying stuff, no deeper reality (than my iPhone). There is only change (which he likened to fire). There is no Being, only beings that are in a constant ferment of change. Later Nietzsche becomes very fond of Heraclitus. Declaring that God is dead is much the same thing as saying there is no apeiron, no Being.

Parmenides, following the same logic—a thing cannot be both infinite and finite—reached the opposite conclusion: there are no beings, change doesn’t exist. The only reality is the indefinite infinite, Urstoff, apeiron, or Being. Parmenides took a step further, adding the idea that the underlying substance or otherness must be singular because if there were more than one, it wouldn't be infinite. He called it the One. And it is perfect. In fact, the One is beyond Being (if you can imagine that), since Being is conceived in relation to being. The One is without relation; it is unthinkable. Where that leaves us (uncertain, temporary beings in the here and now) is difficult to tell, and apparently Parmenides had no clear answer to the question.

There is some evidence that besides vigorously wielding the law of non-contradiction he also practiced incubation, sleeping in sacred places to invite dreams from the gods. The proem to his great poem “On Being” reads like a katabasis, a Journey to the Land of the Dead. Led by a band of maidens, daughters of Helios, a team of dashing mares drags the philosopher’s chariot, the wheels whirling, spinning, screeching with the sound of pipes, up to the very gates of the paths of Night and Day where a goddess (Persephone) greets him and pushes the mighty doors open.

Parmenides and Heraclitus set the stage for Plato who teaches that two worlds exist, the world of shadows and imitations (a.k.a. the sensory world, the world of beings with a lower case b) and the real world of universal, infinite perfection governed by the Good, which is his way of characterizing the conceptual space indicated by Anaximander’s infinite, undifferentiated underlying stuff. Plato dramatizes his two-world theory with his Parable of the Cave. Humans sit in the cave mesmerized by the play of shadows on the wall; few if any have the courage to turn and look at the fire (fire again). The fire is the Good, the real, the source of true knowledge, while the shadows are only the silhouettes of the watchers themselves, secondhand, (degraded) images. By analogy, the world we humans inhabit is only a fuzzy version of the real world, a gray outline lacking definition and detail; and Anaximander’s apeiron has suddenly and paradoxically become crowded with things: the Good, the Beautiful, and souls, as well as what Plato called Ideas (usually spelled with a capital I), which are both concepts (the concept of a rabbit) and somehow real objects in that unseen-but-more-real world, the perfect and singular rabbit, of which all rabbits on earth are pale imitations.

In a certain light, Plato’s Ideas have always seemed to me suggestively reminiscent of the totems and spirit animals of oral traditions. I am aware that this is a heterodox, if not heretical, observation, Plato channeling his inner shaman. He was comfortable discussing oracles, reincarnation, and various myths and legends and in so doing showed at least that he knew his audience was saturated in the discourse of the ancients. There is a popular (modern) idea that philosophy progresses in logical steps, each new set of ideas consigning all previous arguments to the waste bin. But the opposite is in fact the case. The old ideas carry on in one state of vibrancy or another alongside the new ideas. Sometimes people just don’t get the message (certainly an issue in Plato’s time when most people still lived in a state of illiteracy), or they get the message and refuse to believe it. The old ideas fight a rearguard action against the new; various sorts of religious belief, surprisingly to some, have never gone away. Or the old ideas persist in an etiolate secondary state, kept alive by romantic nostalgia. Instead of inspiring awe and epic poetry, they inspire fiction.

Anaximander’s intuitive leap is to invent modern philosophy by giving a logical definition of that other world of Being (myth turned to concept): timeless, undifferentiated, indescribable, and unknowable. But the vast majority of people, thinkers and otherwise, pay scant attention. The Greek shaman, the orators, the rhapsodists, the priests of the mystery cults proceed as before. The weakness of the logical argument is in its negative (apophatic) torque; we can’t know apeiron, so who’s to say there aren’t gods, totemic animals, or a mysterious entities like Ideas, Beauty, or the Good. You can call this will to populate apeiron belief (as in religious conviction) or poetry (as in Plato’s beautiful analogical parables and his arguments from myth), but it amounts to a relentless retrenchment of the old, a colonization of the new by ideas that have been ingrained for tens of thousands of years.

5 – Plato’s Divided Line Argument

The new philosophy is more abstract and logical than the ancient legends, and it is less intimate and terrifying; we begin the slow march away from the truly frightening aspects of metaphysical—or divine—difference. So-called facts and definitions begin to pacify the antique, fluid dream-world of mythic beasts and changelings. The membrane between the two worlds becomes less permeable. This created all sorts of ethical and epistemological problems for people who generally wanted to keep to the old belief in the divine. If you can’t simply go on a journey, dream, fast, meditate, pray, or drug yourself into the other world, how do you know it exists? How does wisdom transfer from one world to the other? Magical interventions? Miracles? Demons? How do we know what is Good or what God’s commands are? The problem presents itself as one of mediation. How do messages get from the atemporal, infinite, universal, unitary world of Ideas to the temporal, finite, relativistic, death-ridden land of shadows? This problem may not seem so urgent nowadays, but it kept philosophers awake at night for two thousand years.

Plato provides two answers. The first is that knowledge is recollection. When you learn something new, it’s really the case that you are only remembering something you already knew. This is in his dialogues Meno and Phaedo. Humans are reincarnated again and again, and in between times their souls dwell in the world of Ideas (what used to be the infinite, indefinite apeiron). Thus when they are born into the world of shadows, they are able to recognize what is going on around them because they have grown familiar with their prototypes (Ideas). This is the magical answer that depends on a complicated myth about souls shuttling back and forth from the invisible to the visible world. The myth of reincarnation disappears in later philosophies, but thinkers return again and again to the puzzle of innate ideas (or what Levinas characterizes as the return of the Same) and the paradox that we seem to need to know something before we can know anything. This paradox is perhaps the nub of what Plato was getting at.

His second answer is that by study, discipline, and the contemplation of mathematics, humans can reach higher and higher levels of knowledge until they achieve the light of the world of Ideas. Certain super-achieved individuals can train their minds to sense (intuit and apprehend are fuzzy words often used by philosophers to name this process) Being, or as Plato wants to call it, the Good. This is the still-magical-but-less-so answer, seductively grounded in the elegant purity of geometry and supported by several arguments from analogy that are more persuasive than plausible.

In The Republic Plato outlines his discovery-of-the-real-through-contemplation theory, but it’s difficult to make perfect sense of how this might work in practice. First, he re-imagines the world of Ideas on an analogy with the world of shadows. The sun provides light in the world we experience just as in the supra-sensible world the Good provides the light of wisdom. Then follows his famous divided line argument.

...bearing in mind our two suns or principles, imagine further their corresponding worlds--one of the visible, the other of the intelligible; you may assist your fancy by figuring the distinction under the image of a line divided into two unequal parts, and may again subdivide each part into two lesser segments representative of the stages of knowledge in either sphere. The lower portion of the lower or visible sphere will consist of shadows and reflections, and its upper and smaller portion will contain real objects in the world of nature or of art. The sphere of the intelligible will also have two divisions,--one of mathematics, in which there is no ascent but all is descent; no inquiring into premises, but only drawing of inferences. In this division the mind works with figures and numbers, the images of which are taken not from the shadows, but from the objects, although the truth of them is seen only with the mind's eye; and they are used as hypotheses without being analyzed. Whereas in the other division reason uses the hypotheses as stages or steps in the ascent to the idea of good, to which she fastens them, and then again descends, walking firmly in the region of ideas... – The Republic, Jowett translation.

I give you this long quotation because this is precisely where a basic card deck of elementary philosophical gambits begins (Jacques Derrida calls Plato’s Republic “quasi-inaugural”). By gambit I mean a rhetorical strategy, a pattern of argument that you find recurring throughout the history of philosophy in different contexts and arenas (the larger structure of philosophical discourse seems modular with entire syntactic strings patched in where needed with only slight variation). However you doctor this up with glosses and interpretations, Plato depends on arguments by analogy to create mental pictures, assumptions, and new myths in order to make claims about the nature of Being. Thus philosophy blends with poetry in the effort to represent the unthinkable (apeiron), which effort is at the root of much that is difficult in philosophical discourse.

Plato offers four classes of analogy: physical, social, spatial, and mathematical. The Good is like the Sun, which makes objects visible by shining its light on them. At various points in The Republic it also becomes a king and a father. How far Plato meant us to take these arguments, to what extent he meant to move from analogy to ontology, from “like” to “what is,” remains poetically vague. Yet it is such an appealing picture that we easily forget that we’re only dealing with a figure of speech. This is standard operating procedure for humans; we are always using the familiar to colour the ineffable.

Plato’s spatial analogy is more intricate and intellectually seductive. It consists in picturing the two worlds as two sides of a floor plan with a line driving up the middle that connects them, then inserting the ideas of gradation and stages of progression. At the beginning of the passage, Plato uses words like “imagine” and “assist your fancy,” but by the end he has reason “walking firmly in the region of ideas.” Note the lovely slippage in the diction from “segments” of a line, to “stages of knowledge,” and thence to “upper” and “lower” stages. We are in the realm of speculation, especially insofar as we’re concerned with the part of the divided line that stretches into the invisible world where we can neither inspect nor conceive the furnishings.

But Plato is leading the reader through a series of increasingly abstract analogies, deeper and deeper into the concept of the invisible world (apeiron, as if you need reminding). His spatial analogy, the geometric floor plan, slides easily into his argument from mathematics. First, he distinguishes between knowledge gained from observation, “from the shadows,” and knowledge “seen only in the mind’s eye.” “Seen in the mind’s eye” is another poetic but deceptive metaphor; it suggests that the mind has a special “eye” that can see, apprehend or intuit objects (Ideas, the Good, etc.) in the invisible world. Then he claims a special position for mathematics (above the horizontal line) because it is a product of thought and logic (the mind’s eye) and presents concepts that are independent of observation. In this sense, mathematical knowledge seems identical with knowledge of Ideas; they both apply to invisible things.

The nature of this identity is problematic. The mathematical argument trembles between analogy and syllogism, between suggestion and ontology, between “is like” and “is,” and as a syllogism it suffers from the fallacy of the undistributed middle. This is the difference between science and poetry. Metaphors are based on partial identities. The dancer floats on butterfly wings connects a dancer and butterflies because they both float on the air. But to say that dancers and butterflies are identical because they both float is faulty logic. Floating is different in each case, or as the logicians say, the middle term “floating” is not perfectly distributed among the other two terms. It exhibits slippage; if you drew Venn diagrams, floating1(dancer) would not precisely conform to floating2(butterfly). Over and over again in philosophical discourse we discover similar arguments, analogies that suggest syllogisms, metaphors that almost allow you to glimpse the other world. I call these philosophical apex arguments, arguments that run up to the boundary of what language can express about that other world, the real, apeiron.

Communicating between two worlds11 certainly seems easier if it only means climbing a ladder by simple steps as opposed to leaping across an infinite abyss. The fact that the two worlds still don’t link up, that they are only contiguous metaphorically is glossed over (as in Zeno’s paradox: we get closer and closer to the invisible world without ever getting there). But the difference between finite and infinite is not a line in the sand; it’s an abyss—at least, that’s what we often call it. In this argument from analogy Plato has reimagined the shaman’s journey up the Tree of Life and Death, albeit in less heroic, more earthbound and secular way. And his image of a graded reality (a continuum) soon spawned what became known as the Great Chain of Being, the fanciful yet seductive (for hundreds of years) idea that all creation is a hierarchical structure ascending from the meanest creatures to the angels and God.12

4 – Plato’s Posterity, New Myths of the Other

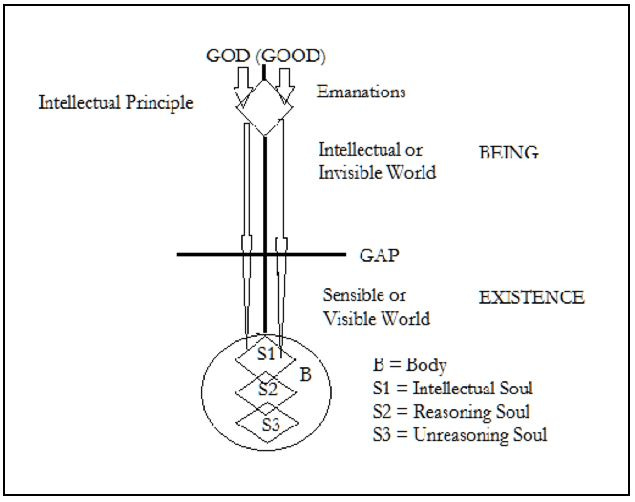

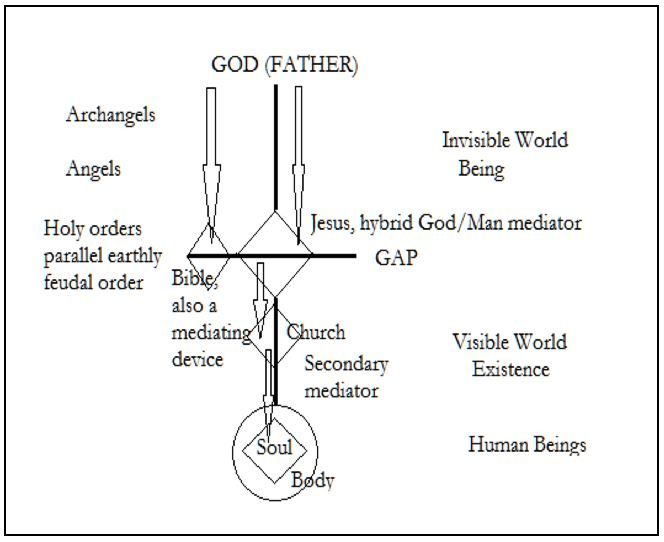

Plato’s metaphysical dream acquires myriad footnotes, glosses and elaborations over the next few hundred years. Typical is the Alexandrian philosopher Plotinus who elaborates on the two-world theory and the divided line by adding and subdividing new gradations of being and new beings. I don’t have the space to spell out his complexly elaborated system completely, but Plotinus starts with the One (Good or God) at the top and then there is an Intellectual Principle which isn’t really a principle but a sort of mediator entity that comes between the Good and the next layer of being which is the Soul. And then the Soul divides into Intellectual Soul, Reasoning Soul and Unreasoning Soul. Communication or mediation between the levels of existence takes place by means of something called emanation, which is a variant of the sun or light metaphor.

You can imagine this as a series of crystals that receive and redirect the light from some original source, but you can see that this is simply an exfoliation on the pattern of Plato’s arguments from analogy and metaphor. None of this can possibly refer to anything remotely real, and the multiplication of grades, entities and metaphors is positively Monty Python-esque. And it doesn’t solve the two-world problem, rather it just moves the problem around. For example, for Plotinus the Soul belongs to the intellectual or invisible (eternal, infinite, etc.) world, albeit at the bottom level. At the bottom level of the invisible world, the Soul somehow enters and resides in the visible world, in a Body (never mind the paradox of something infinite being contained inside something finite). But then, Plotinus quite correctly wonders, how does the Soul communicate with the Body? A question like this provokes a deluge of metaphorical possibilities.

But, we ask, how, possibly, can these affections pass from body to Soul? Body may communicate qualities or conditions to another body: but- body to Soul? Something happens to A; does that make it happen to B? As long as we have agent and instrument, there are two distinct entities; if the Soul uses the body it is separate from it.

But apart from the philosophical separation how does Soul stand to body?

Clearly there is a combination. And for this several modes are possible. There might be a complete coalescence: Soul might be interwoven through the body: or it might be an Ideal-Form detached or an Ideal-Form in governing contact like a pilot: or there might be part of the Soul detached and another part in contact, the disjoined part being the agent or user, the conjoined part ranking with the instrument or thing used. —The Enneads First Tractate, 313

Once again note the linguistic slippage from the abstract rational-seeming discussion of A and B to the metaphors coalesce, interwoven, and pilot.

This is the kind of philosophy that Nietzsche called a lie. The problem of difference is simply ignored in the multiplication of metaphoric semblances. The terrible Other is conceptually caged and tamed. But, of course, that’s not the way people thought of it at the time. For a thousand years philosophers and theologians elaborated and diced their schemes, shifted terminology, and took seriously debates about things like how many angels (infinite beings) could fit on the head of a pin (finite point). (This is not as silly a debate as it might seem to us. These thinkers realized there was a problem when they tried to insert an infinite object inside a finite object, thus pins and angels are just an aspect of a larger argument.) In general, people took such dichotomized entities as Soul and Body, Heaven and Earth, as real and also accepted the reality of some, possibly ill-understood, mediating mechanism–the word “emanation” looks perfectly clear in a certain sense. But reflecting from our 21st century eminence, it now seems evident that philosophy merely traded one mythology for another.

Schemes like the one Plotinus invented blend easily with Christianity14, offering a pseudo-rational backing for the paradoxes of the birth and death of Jesus. So much so that it’s difficult for us today to really imagine how easily and thoroughly people acquiesced to the current modes of discourse (unless we happen to notice how easily and thoroughly we acquiesce to our own narratives today). These, to us, cockamamie conceptions seemed perfectly natural at the time, as self evident as the laws of gravity today. The metaphors were, in Marx’s terminology, reified; they came to be thought of as real things. Or the metaphors became myths; Christianity seen in this light is a retrograde movement in the history of Reason, a remythification of ideas Anaximander had attempted to purify of myth (incompletely, as it turned out).15

5 - The Book and the Other

The pattern of philosophical dream changes again with the advent of printing and the Protestant Reformation, the onset of modernity. Printed books provide another leap in the technology of external memory storage and retrieval. They make possible the invention of modern science and capitalism (based on advanced record-keeping instead of hard cash or gold; money begins to become the complete abstraction it is today). Reading becomes a generalized human activity; a publishing industry sprouts up (one that has remained fundamentally unchanged ever since); the idea of a reader alone with his book changes our concept of privacy and raises the suspicion that books are anti-social, seditious, and pornographic.

Luther translates the Bible into German and democratizes access to the Word of God; this disrupts the 1,000-year pattern of sacral and intellectual authority established through the church and based more or less on Plotinus through Augustine. The book itself becomes a mediating entity, an app, a theoretical gateway to the invisible world of God in Heaven, and any literate individual can find his own way there. As soon as Luther mounts his revolt against the universal church, the earthly image (analogue) of the One and his invisible universe of intermediaries and emanating wisdom, the old philosophical game is over.

At first Luther, Calvin, and the Roman Catholic Church try in their own ways to control the process, but like a nuclear reaction gone amok authority splits and splits again spawning competing liturgies, competing interpretations of the Bible, competing translations and finally, good grief, biblical criticism which ends up showing God had editors thus undermining the Bible’s position as a mediator. And in the midst of this frenzy of thought and reshuffling we get the first glimmers of the modern idea of a self separating itself ever so slightly from the ancient idea of the soul-body or human-animal hybrid being.

Descartes is the first philosopher to apply the new critical modes of thought, and he quickly reduces all prior metaphysics to shambles. He begins by establishing a strictly logical version of the two-world theory. Then, applying his new method of Radical Doubt (which is, in fact, the old method of applying the principle of non-contradiction), he systematically demolishes all claims about reality, even the existence of God, who, Descartes realizes, could quite easily be an evil demon sending him corrupt messages about what is out there. What he is left with at the end is the famous Cogito, ergo sum. I think, therefore I am. The only thing humans can really be sure of is that someone is thinking (conscious) and that the thinking exists, although it could be a continuous hallucination or a coded message sent from the planet Neptune.

This alarming idea is too much for Descartes who never meant to end there anyway. He immediately applies a subtle and complicated version of Plato’s fallacy of the undistributed middle (the apex argument) and deduces the existence of a beneficent and truthful God, so that God can go back to being a guarantee for the reality of reality. From God, he proceeds to deduce the whole two-world apparatus and mediating processes all over again. This part of Descartes’ philosophy is a dubious achievement and not so interesting. But he otherwise has two profound effects on what happens later. 1) He establishes once and for all the completely paradoxical nature of claims about another real world beyond the world of the senses. Before this people could go around saying God sent his Son to save the world or the One emanates knowledge through the Intellectual Principle to the Soul and think they were making sense. After Descartes, at the very least, they have to shuffle their feet and cough and try to make excuses. 2) With the famous Cogito, he shifts the focus of philosophy from the nature of underlying reality (apeiron) to the nature of consciousness, that is, how we think and know. This has a huge effect in the 20th century when Husserl reinvents Descartes’ crisis in philosophy and discovers phenomenology, the philosophical study of consciousness.

A pattern of philosophical inquiry should now be familiar. First, you tear everything down (applying the law of non-contradiction) and then proceed from basics (inarguable axioms) to rebuild the apparatus. One common axiom is that existence must be backed by a more stable and substantial reality that we can’t access in any normal way. At the apex of the new architecture you find arguments that use analogy to suggest what the other world is like and how we can communicate with it. Not till Nietzsche do you find a major philosopher willing to side with Heraclitus and say, well, there just isn’t anything there.

Immanuel Kant, paladin of the Enlightenment, was branded “der Allzermalmende,” the all-destroyer, for apparently putting an end to all those so-called rational arguments for the existence of God. The effect of Descartes’ Radical Doubt and the advance of science (especially Newton’s physics, which promised to reveal the hitherto invisible laws of nature) is that it is now incredibly difficult to say anything about a world beyond the one we inhabit. In a section of the Critique of Pure Reason called “The Antinomy of Pure Reason,” Kant demonstrates the paradoxical nature of any argument claiming authentic knowledge of a suprasensible reality; he does this simply by presenting a series of rational arguments that both prove and disprove the same proposition (an inkling that—foreshadowing Jacques Derrida and deconstruction—the problem isn’t one of reality but of language itself).

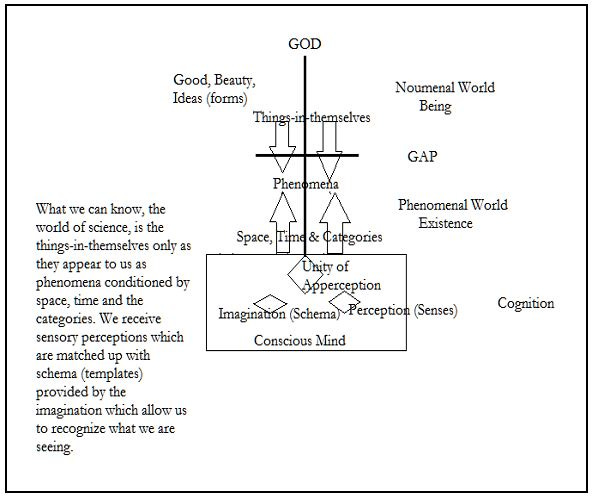

In the remainder of the Critique, Kant conceptualizes the way we acquire knowledge by inventing an elaborate structure of faculties (mental machines), filters (what he calls the “conditions of knowledge”—space and time plus twelve basic Categories of objecthood), and mediating devices (a little app called the schema of the imagination). At the top of the structure is a governing device called the unity of apperception (a.k.a. the “I” at the centre of knowing). Kant’s system is startlingly reminiscent of the radical leafing out of hierarchies and intermediaries of earlier philosophies except that now the mediating system no longer stands between reality and the human mind but somehow inheres in the cognitive apparatus itself.

The best way to imagine this is to think of the mind as a personal computer. It has an operating system that comes from Microsoft (this operating system is what Kant calls the transcendental unity of apperception) that governs what we can see on our screens and store on our hard drives. Much of this operating system is in the form of hidden files, which we don’t normally access. What we can access is dictated by the capabilities of the operating system and the sorts of files it can read or generate, for example, an image file, an ordinary text file, or a database file.

Kant’s “conditions of knowledge” are much like the code that allows the computer to recognize, identify, and read files. According to Kant, our human operating system is only coded to recognize and read objects that present themselves in space and time (tagged for space and time, as it were). There may be other kinds of entities (files), entities that might be eternal and infinite, but they’ll never appear on the screen. (The difference between computers and real life is that in real life you can’t just write yourself another cognitive app—that’s what metaphysics means.)

Kant’s answer to the ancient problem of how Being becomes being, how apeiron becomes an iPhone, is simply that it doesn’t matter. The fidelity and consistency of nature and daily life is guaranteed by our internal filtering system: space, time, and the Categories. For the purposes of day-to-day life and science, the other world is irrelevant, so separate and different as to be inoperant. What we cannot observe does not touch us (we cannot even talk about it except in terms of analogy and metaphor).

By severing the two worlds, Kant thought he had saved both from mutual attacks and doubts. God, superstition, and miracles were banished from nature and science; science and reason could no longer invalidate the divine. A lifelong Pietist, he had built an inviolate space for faith. But it was a Pyrrhic victory. His absolute separation of sensory existence from Being (and the divine, etc.) especially befuddled him in regard to ethics, and he turned himself into a pretzel in the Critique of Practical Reason trying to prove that we somehow get impulses or messages or intimations from world of Being (God) that tell us what is right and wrong in this world. A German word that keeps cropping up in this context is Ahndung, which translates as presentiment, premonition, clue or hint. Freud uses the word three times in his famous essay on the uncanny.16

With Kant, we have reached the height of the Enlightenment which, as Theodor Adorno observed, is much taken up with the demythification of philosophy. In fact, the process of demythification begins with Anaximander, and we can imagine it as a progressive knocking down of bridges between the world of appearances and the real world of Being. Of course, most of the time philosophers knocked down bridges and invented others with more rational-sounding names. And there have, from early times, been strict materialists who deny the existence of other worlds, but oddly enough they have never captured the imagination of the great thinkers. The two-world thesis has that quality which, in the computer world, we call “stickiness.” But the evolution of thought parallels a progressive distancing of the world of appearances from the world of reality, man from God, earth from Heaven, and philosophy itself realizes that it has less and less to say about what is really real. As always, Descartes’ demon god systematically deceiving mankind remains a nightmare of the terrifying Other best avoided.

6 - The Death of God

In 1882 in The Gay Science, Nietzsche announces that “God is Dead” (later, and more famously, repeated by a character in Thus Spoke Zarathustra), which marks a brutal close to centuries of philosophical moonshine, except that it doesn’t really put an end to anything because people just can’t bear to give up on the archaic idea that there is something more than the inscrutable, absolute indefinite—apeiron—so different, distant, and untouchable that it might as well be nothing. Joseph Conrad’s narrator Marlowe calls this archaic remnant “the great and saving illusion that shone with unearthly glow in the darkness.”17

Essentially, Nietzsche does nothing more than cap a growing awareness, since Descartes, that really we can’t make substantive claims about the existence of worlds other than this one, the world of appearance, the world of existence. The two-world argument hits the wall and with it goes all the old arguments deduced from a transcendent reality or an other-worldly God or Good, upon which, for hundreds of years, we had founded moral and social structures and hierarchies. What happens next is that philosophy splinters itself into a number of paths or solutions.18

1) Hegel, Marx and the Reification of History: Hegel, who actually precedes Nietzsche, historicizes the two-world structure (and Plato’s divided line) and says that the other world is not contemporary but in the future (the mysterious out there becomes the equally mysterious later). History is about the growth of the human spirit, the acquisition of knowledge building toward a moment (somehow) of unity or coincidence with the totality of the world Spirit. This is a quasi-Christian fudge which quickly convinces hardly anyone except Karl Marx who jettisons the spiritual aspect of History from Hegel’s system and replaces it with the idea of human development from feudalism through capitalism and the dictatorship of the proletariat toward a system of perfect socialism when we will all be equal and good to each other like people in Heaven. This also seems pretty New Testament, although Marx would deny it. In this view, History itself is constructed as a universal, totalizing process, as myth.

2) Hegel, Marx, the Frankfurt School and Critical Theory: Both Hegel and Marx have other better ideas. They both respond to the refocusing of philosophy on human consciousness. Hegel, for example, does a brilliant analysis of the master-slave relationship (he is already calling this phenomenology), demonstrating how humans reciprocally create one another in social situations. Marx contributed his own brilliant analysis of the virtual reality machine created by fetish capitalism. People are not only defined reciprocally in social relations, those relations are defined by the abstract flow of desire and capital. Capitalism orchestrates vast numbers of humans to produce and churn value, this churning of an abstraction for which no one has any real use creates alienation (meaninglessness, anxiety and the desire to chase even more abstract value). This is not philosophy in the old style at all. This is philosophy turning its analytic tools on the complex fever of the here and now and finding that our reality, our sense of self, is far less stable and substantial than we thought. Not only is there not a God and another, better reality, there may not even be an “I” we can call our own.19

Aside from the dolorous history of Stalinist Russia and the Cold War, Hegel and Marx have a profound effect in the 20th century via the Frankfurt School of philosophy or what we call Critical Theory or culture criticism. Philosophers like Theodor Adorno apply methods of social and cultural analysis, tools derived from Hegel and Marx, to expose systems of oppression and delusion in contemporary culture. Adorno doesn’t even shy away from analyzing popular culture, seeing the media, for example, as an instrument of control and oppression in favour of market capitalism. In effect, humans now live in a delusional system of artificially directed desire and satisfaction. Our thinking is done for us. I think, therefore I am has been replaced by I am a passive receiver, therefore I am.

Critical Theory is not a positive philosophy; it makes no substantive claims about reality or the future because it is theoretically bound to analyze its own activities which must also be considered suspect (why do we valorize freedom over oppression or deep thought over shallow fantasy?). A modern version of Descartes’ Radical Doubt (or the strict application of the law of non-contradiction), Critical Theory is a stern and irritating moral force, relentlessly telling us what’s wrong without offering a clear escape route. Yet when all escape routes are illusory, one begins to yearn for escape from existence itself, the fallen world. One begins to see why those dangerous pathways into the world of the Other held a certain appeal.

3) Existentialism and the Aesthetic Argument: Kierkegaard follows Hegel and rejects that system-building dream. His first book is on Irony. A later book The Present Age pretty much describes the world we find ourselves in today. “...the present age is an age of advertisement, or an age of publicity: nothing happens, but there is instant publicity about it...Action and passion is as absent in the present age as peril is absent from swimming in shallow waters...” Without the Other, without God, without something more real and dangerous than the visible world, humans settle into a disastrously undramatic, narrow-minded, petty, alienated mode of living much like the one Marx describes. “Men, then, only desire money, and money is an abstraction...” Kierkegaard realizes he can’t create rational arguments for the existence of the divine; that train has left the station. His solution is to displace the two-world argument from metaphysics to the mind. The Leap of Faith is a state of consciousness that anxiously (despairingly) embraces the paradox of believing in what can never be known (including, in Kierkegaard’s case, the entire Christological narrative).20

Nietzsche and Kierkegaard have a lot of similarities. They are both wonderful writers, both can be quite funny, both tend to write in off-forms--fragments, aphorisms, fictions. They both accept that the long ride of the two-world argument is over and despise the cultural situation we are left with. They are both proto-existentialists because they stop making claims about the world beyond and concentrate on the human situation now, existence, and the act of choice. They both also valorize a supposed past state when “action and passion” were more common. This is an aesthetic argument that masks an unwarranted moral argument. Given the premises, there is no reason to value action and passion over money and publicity. But nevertheless, in the name of action and passion, Kierkegaard reinstates religion with the Leap of Faith (a choice) and Nietzsche invents his Dionysian Superman who chooses joyfully to join the struggle to impose his will on the flux of history.

Kierkegaard and Nietzsche bequeath their aesthetic argument to the dead-end 20th century philosophy of Existentialism. Though appealing to poseurs, young people and feverish romantics who like to see themselves as heros, the idea that heroic choice, commitment and passion can somehow make one person’s life more authentic than another’s is poppycock. This is a recipe for good novels, bad marriages and terrible social cruelty. Existentialism founders because of its focus on human choice, as Nietzsche says, for creating value, or as Sartre might say, to create oneself. But if no value exists prior to choice, then there is no reason for choosing one act over another. In Camus’ novel The Stranger the hero, Meursault, murders an Arab because the sun gets in his eyes. This is Existentialism in a nutshell. When Sartre finally reached the dead-end, he became a Maoist.

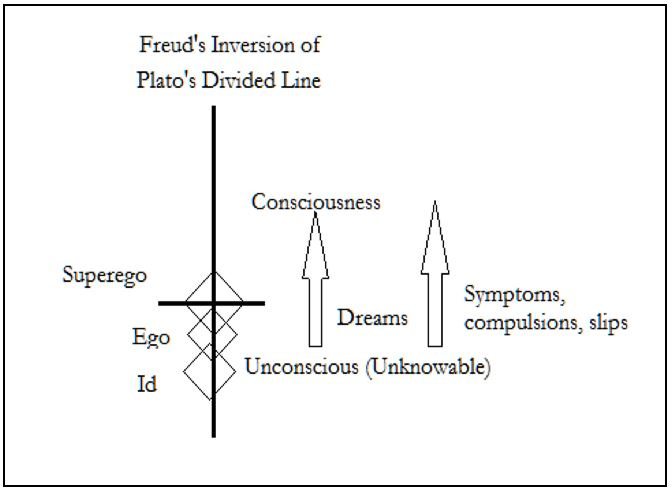

4) Psychoanalysis:21 Freud is a fascinating branch-line in the history of the two-world argument mainly because he makes the astonishing discovery that the Other is not only out there but inside as well. In fact, he doesn’t care much about the Other out there, nor does he mourn the death of God and the loss of the moral-metaphysical framework the invisible world provided. He concentrates on the invisible world inside the human heart where he finds a huge blank spot called the Unconscious which, by definition, we cannot know. (It takes up the spot that used to be occupied by the Soul–infinite, unknowable.) The fact that by definition we can’t access the Unconscious doesn’t stop Freud from imitating Plotinus and inventing a scaffolding of intermediary entities (Superego, Ego and Id; compare with the Intellectual Soul, Reasoning Soul and Unreasoning Soul) and emanations.

He notices that people often do odd, repetitive, self-destructive things for no obvious reason and decides these must be symptoms of Unconscious mechanisms. Dreams are symbolic emanations from the inner unknown that a skillful reader can decode. Freud invents a narrative myth to explain the contents of the Unconscious, something to do with infant sexuality, the desire for sex with a parent, trauma, repression, and the return of the repressed. Oddly, enough this seedy little myth repeats the archaic ban on incest which, according to Levi-Strauss is the foundation of culture, the primal alienation. These concepts can hardly be described as even theoretical. Rather they have the character of suggestive and, yes, compelling metaphors. They cannot be proven because, by definition, like God and the world of the Other, the Unconscious is completely opaque. But Freud and his followers reify the metaphors, and today, in the world of popular culture, we take them as the bedrock of human nature. We may not necessarily believe in our immortal Soul, but we all talk glibly about the Unconscious, as if it we had all seen one.

7 - The Fractured Window Pane of Modernity

In the 20th century, without the gaze of the Other to prop up our certainties and alibi our failings, there is a profound turn in philosophy away from the object, that is whatever might be out there. From Plato on we have been blowing up the bridges between this world and the Other, shoring up the Berlin Wall of difference, gradually admitting our limitations. Our world has grown smaller and more squalid while the compass of the great unknown out there seems to expand even in its infinitude and grows ever more alien.22

The scene is set by Edmund Husserl who published a book on the Crisis in Philosophy in 1935 in which he revisits Descartes’ method of Radical Doubt (aka application of the law of non-contradiction). The crisis amounts to a re-emergence of Plato’s idea that we can’t know what we don’t already know, the paradox of epistemology. Kant had made the crucial step of suggesting that there are certain forms of thought that inhere within the subject (consciousness, people), templates or filters, which make knowledge possible while also, to a certain extent, constructing that knowledge. This formulation stops short of the philosophy known as idealism, claiming only that all knowledge is constructed in the imagination of the subject based on perception of objects filtered by space and time. Thus the way we know becomes a significant part of what he know. We don’t have anything like pure knowledge of the object, but knowledge for us, knowledge compromised by the structure of our apparatus for knowing. If this is the case, it makes sense to study those templates, those conditions of thought, of consciousness itself. Philosophy then abandons its traditional object (the object) and converts the subject (consciousness) into an object of rational inquiry. This coincides with what the post-modernists and the critical theorists and the literary critics later call the abandonment of the Grand Narratives. Henceforth, there will be no over-arching systems, no total theory of human existence or history.

Phenomenology, literary criticism, linguistic analysis, psychology, cultural studies and anthropology all become branch lines of the activity of philosophy just as traditional philosophy and academic philosophy departments begin to dwindle as going concerns. The decisive turn toward language as the primary field of study begins around mid-century but is prefigured in the late 19th century in the arts, which suddenly fracture and turn self-conscious. The technique of art becomes a concern of art itself and the traditional subject (the object of art) recedes in importance. The painting we all know as “Whistler’s Mother” was, in fact, called “Study in Black and Gray” by the painter.

Very early in the 20th century in St. Petersburg, the critical school called Russian Formalism rises in a whirlwind of new aesthetic and political movements. Formalism, the theory that art is content fitted into pre-existing aesthetic structures, coincides with the birth of structuralism, a cluster of theories in various disciplines revolving around the idea that cultural and social entities develop according to recurring structures (forms). Roman Jakobson is an early Formalist who leaves Russia and helps found the structuralism movement, modern anthropology and the structural analysis of language. Vladimir Propp, famous for his analysis of folktales comes out of the same St. Petersburg stewpot and has a huge influence on anthropology (the modern exemplar being Claude Lévi-Strauss who eventually came to the conclusion that societies are structured like languages) and later French literary theory.

Unless you have fully entered the language game of theory, it’s often difficult to comprehend what is being said or how it fits into the general history of philosophy. The structures of thought are, like Kant’s conditions of knowledge, peculiar theoretical entities which require a good deal of metaphorical language in explanation. It is difficult to imagine what it means to say that something inheres in thought and constructs our reality, a reality not the same as reality might be prior to being constructed, a quasi-reality which is still not something we completely made up. One is reminded of Ezekial 1:28.23 “This was the appearance of the likeness of the Glory of the Lord.” But what is an appearance of a likeness of something real? The approach to Anaximander’s apeiron, at the apex, is always shrouded in clouds of metaphor, in similitudes.24

The main premise of the two-world argument is that there is a subject and an object with an immeasurable and unleapable distance (difference) between them. For the subject, the object only appears as an appearance of a likeness. Every particular philosophical formulation of the argument has hypothecated mediators and steps which makes knowledge (or redemption) possible. Since, roughly, the death of God, the argument has shed much of its theological weightiness. Now the argument is less about how we can know God than how we know the world and each other, and here the world is Wittgenstein’s world, the world we can describe in words. But what Kant and the various forms of structuralism have done is invent new mediating machines, the structures of thought/conditions of knowledge (think space stations and docking devices) that somehow allow us to hook into the reality beyond.25

But they are tricky, impossible to pin down. In this regard, the critical analysis of literary texts seems about as far as you can get from traditional philosophy except that literary texts offer lessons in how the mind constructs meaning – read “reality.” Literary criticism of this sort views the experience of literature as a paradigm of consciousness. In this case, the text stands for the reality out there (this really goes back to biblical criticism, the problem of biblical interpretation set against the notion of the Bible as the Word of God). Thus you can get a sense of how contemporary philosophers see the relationship between subject and object, self and world, by watching the way they talk about texts.26

Roland Barthes is famous for declaring the death of the author, which, of course, is a playful repetition of Nietzsche’s death of God moment. The author is in a position to his text analogous to God’s position to the world. The author wrote the words; God created the world. But the subject doesn’t/can’t interact with the world directly, only sees an appearance of a likeness just as the reader never reads the text the author intended but brings his own associations and interpretations. What the reader brings to the text constructs a new text, his own text, a text for himself, the only “real” text he can have. The original text, the author’s text, disappears. The author becomes vestigial. In the same way, the subject brings its own structures to the reality God created. Because we can’t access that reality directly, can only work within the constructed reality of our own creation, God becomes irrelevant. (No doubt this argument is as dismaying to God as it is for authors.) A literary text then becomes valuable less for what it means than for its receptivity to theorizing, theory here becoming a kind of philosophical meta-poetry attached to texts. Hermeneutic vigor, the production of meaning, replaces simple truth as a value.

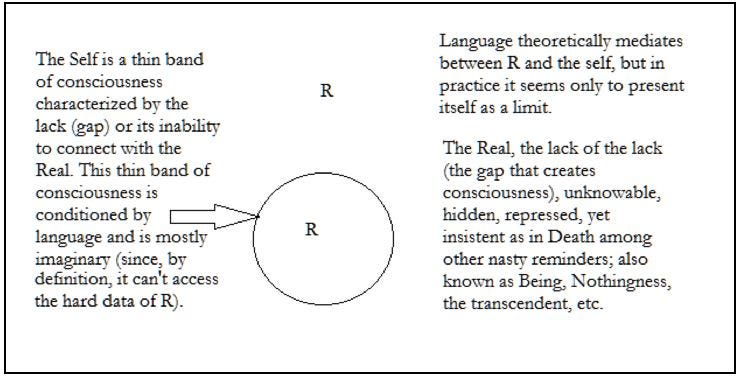

At this point, strangely, language, nowadays considered the chief structure of thought, the primary mediation device between humans and reality, itself begins to float, to exist somehow both inside and outside its human host, creating a structure of meaning and thought which we cannot escape and which, in our imaginations, might be otherwise. Language, the invention that created consciousness and set us apart from Nature in the first place, seems to alienate us progressively even from ourselves. Jacques Lacan, the great post-Freudian psychoanalyst, posits a self or subject that exists mostly in a world constructed by the imagination (Imaginary) and language (the Symbolic).

For Lacan, the Real, the psychoanalytic version of apeiron, is both out there and inside, but always unknowable. Consciousness is the original rupture with whatever goes for reality (the Other, the Real, Being, God, primal unity, apeiron). What I have been calling the gap between self and object, Lacan calls the “lack.” Consciousness is consciousness of something, and that something is separate and apart from the conscious mind. This separation, this difference, this lack of identity between conscious mind and object, characterizes consciousness; it is the Lacanian lack. On the other hand, the Real, in Lacan’s recondite terminology, is the “lack of the lack”–i.e., it lacks consciousness (which is a lack) and cannot be an object of consciousness. Yet the Real is also threatening, somehow insistent (because it’s real), and disruptive; it waits with cavernous jaws, hungry and inevitable. What we have been calling the conscious self begins with an absence (lack) and mostly fantasizes itself against that blank screen of the Real (as if, yes, we were back in Plato’s cave. Thus not only has reality disappeared, not only have God and the author become afterthoughts, but even the self, as it comes under scrutiny, begins to dissolve.

Nowadays, the self resembles nothing so much as a soap bubble with a dark and infinite out there and a dark and infinite interior and a thin, iridescent film of consciousness, ineffably fragile and shifting. This consciousness, this self, cannot even call its thoughts and desires its own; in the language of the internet, the self has become an access point and a media reader–thoughts run through it, they can hardly be said to belong. It is as if philosophy, having set out to prove and establish reality, self, God and soul, has only managed to cast doubt on everything it touches. Philosophy is like a wonderfully entertaining magician who ascends the stage, pulls a rabbit out of a hat, then makes the rabbit disappear and then disappears himself.

This is both comic and somewhat tangential since that which began by trying to explain the experience of the terrible Other has not really helped matters by coming up with the idea that there really isn’t an Other and there isn’t any self to experience him anyway. Somehow this doesn’t jolly me out of my fear and expectation of death. For that, most humans still rely on myth and bravado (Nietzsche was big on bravado). In our own minds, we like to pretend we are still the subject of the sentence.

My years at Edinburgh and the trials of dissertation writing are chronicaled in an essay called “Whisky Chasers,” published at Minor Literature[s].

At first, he later remembered, it meant nothing, it was too glistening, too pure. It kept pouring out, more and more insane. He could not identify, he could never repeat, he could not even describe the sound. It had enlarged, it had pushed everything else aside. He stopped trying to comprehend it and instead allowed it to run through him, to invade him like a chant. Slowly, like a pattern that changes its appearance as one stares at it and begins to shift into another dimension, inexplicably the sound altered and exposed its real core. He began to recognize it. It was words. They had no meaning, no antecedents, but they were unmistakably a language, the first ever heard from an order vaster and more dense than our own.

James Salter “Akhnilo”

The key issue in Western philosophy, perhaps all philosophies, is that there are not one but two realities. Humans inhabit a dual universe. At least, they think they do. Whatever reality is in reality, humans experience it as a relation between perceiver and perceived. They never experience what Anaximander called apeiron or Kant called things-in-itself or what Plato called Ideas or Forms or what Heidegger called Being or what Freud called the Unconscious or what Jacques Lacan called the Real. There is a popular misconception that if we could just turn a switch and stop thinking in this peculiarly dualistic way we would all be happy, well-adjusted, fully-creative, left-brain bodhisattvas. But we can't. The duality of the real is based on the universal human experience of a faulty connection between the conscious I and whatever is out there (often indicated by a dismissive wave of the hand). This is not a problem of belief, upbringing, or cultural difference; it’s a problem in the structure of consciousness itself. By becoming conscious we become separate.

Thought Points:

Think of bridging metaphors: the Tree of Life, Jacob’s Ladder, the Great Chain of Being, flying, the Journey to the Land of the Dead, caves, Heavenly Gates, magic doorways. Such motifs appear often in literature. See, for example, the gate-like mausoleum in the opening of Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice” or the Norn-women guarding the office ante-room in Brussels at the beginning of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness.”

Think of meditative disciplines, techniques for bridging the gap between the two worlds and creating an ecstatic sense of oneness: trance dancing, simple repetition of meditative phrases (e.g. the Jesus Prayer), yoga, quietness, drugs (peyote, for example), tantric sex, pain (for example the Sun Dance of the Plains Indians), prayer, fasting, isolation, chanting, drumming, etc. Schopenhauer suggested that creating art is somehow an avenue to transcendent Being.

The Theory of Technological Thresholds

Human thought advances in stages that can be linked to technological advances in memory storage. I do not mean a version of McLuhanite technological determinism. The medium isn't the message. But there has been a progressive change in the way humans store information, and with each sweeping technological revolution there has been an exponential increase in the amount of data entered into memory and a corresponding alteration in the sorts of thoughts we can entertain.

I. Orality: Memory is biological. It resides in the individual human brain and is passed from one individual to another using recitation, rote-memory and rites of passage. Oral cultures link myth, legend, natural and astronomical lore and social structure in a series of mirroring reciprocal mnemonic devices.

II. Writing: Memory stored outside the human brain. This allows for the comparison of text and memory (the first step in critical thinking). It destroys traditional (oral) social (mnemonic) structures, but opens the way for modern accounting (capitalism), science and history. At this stage, the pre-Socratics, then Plato and Aristotle, begin to apply Reason to the ancient myths. Wisdom becomes knowledge.

III. Printing: Printing allows for a vast increase in memory storage and dissemination (networking). The democratization of the book promotes the liberation of the individual self from traditional Christianity. We have the Protestant Reformation, the Enlightenment, money as an abstraction, increasing pace of scientific and technological advance (as more and more knowledge accumulates).

IV. Computers: Vast increases in memory storage, near instantaneous search-and-retrieval systems and world-wide networking. The human brain is a network node and project assembly point. God is dead, but Biblical criticism increases. Increasing pace of scientific and technological advance. Money becomes a complete abstraction. The gold standard is abandoned (like God and the Author). Knowledge becomes information.

The Theory of Technological Thresholds II

The first technological revolution in regard to memory is the human acquisition of language. This seems a little counter-intuitive; language is about communication not memory storage. But I would argue that language is primarily a storage and retrieval tool. The problems of memory are how to get data into a storage unit, how to retrieve it from the storage unit, and the security and durability of the storage unit. Prior to the acquisition of speech, the storage unit for proto-humans was the individual brain. The primary input devices were the senses. Once in the individual brain, for as long as the person could remember, the data was stored and useful for that person. Communication, if any, depended upon mimesis, demonstration and enactment.

Language is a device for encoding data and moving it from one biological storage unit to another. The huge leap of language acquisition allowed people to share stored memories and even to economize by division of memory labour. In any cultural unit certain memories could be assigned to certain unit members. Freed from remembering everything he needed, an individual cultural member would have a certain amount of surplus brain capacity to think and remember new and more complex ideas. (This is a fascinating way of conceptualizing the division of labour in society, not as labour per se but as memory storage: certain people know "how to" to do certain things which frees other people up to know "how to" do other things.)

People quickly invented secondary memory aids, things like ritual repetition, painful rites of initiation (pain reinforces memory), and structural analogies (village or tribal structures parallel mythological phenomena; cave paintings and star constellations repeat myths; in Australia, the Aborigines plotted their mythic narratives on the land itself). Thus oral societies grew up around the need to store, retrieve and pass on complex memories that could only be stored in individual biological data banks called brains. In the oral universe, society itself is a mnemonic device. In such a society there is immense respect for the wisdom of elders; this respect is pragmatic because older people, theoretically, have more experiences stored as memories. This proposition expresses a couple of "natural" values: 1) In an oral society, experience is a primary data source. 2) The more memory stored in a device, the better.

Then the terrible silence fell upon us again. I was no standing and watching a cat’s-paw of wind that as running down one of the ridges opposite, turning the light green to dark as it travelled. A fanciful feeling of foreboding came over me; so I turned away, to find to my amazement, that all the others were also on their feet, watching it too.