The electrifying tale of my Puritan ancestors, how they ended up in New Jersey speculating on land, cheating the government on building contracts, and hosting cock fights at a tavern called The Dark Moon.

My New Jersey Homeland

I just got the results of my Ancestry. com DNA test. I am English and Northern European (Ancestry bangs this group together), Scottish, Swedish (and Danish), and Irish, in order of diminishing significance. This was a surprise to me. I always thought my ancestors came from New Jersey. That’s what I tell people when they ask. I could have been another Bruce Springsteen, if my family had just stayed put.

I am being only mildly facetious. Yes, I am English, German, and possibly French Huguenot on my father’s side. The Scotch and Irish blood comes from my mother. But the people on my father’s side did mostly end up settling in New Jersey until the American Revolution, after which they absconded to Canada because they could see what was coming and didn’t like it (malls, pickleball, Pilates, and Mediterranean diets). Also they wanted to stay loyal to King George because they deeply valued unbalanced, ineffectual monarchs. Ancestry did provide a delightful little migration map of my so-called ancestral communities which shows this.

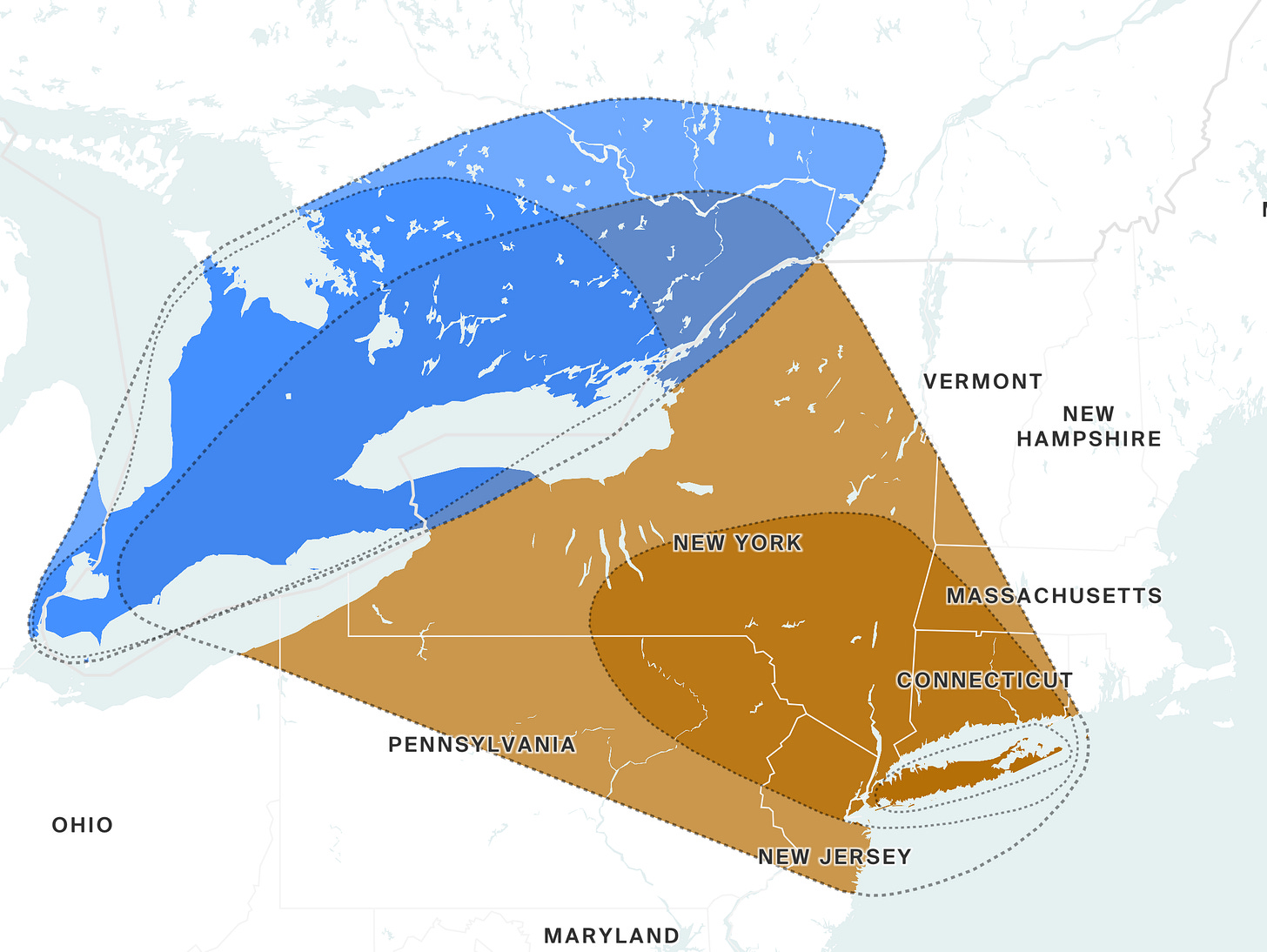

The dark brown patch containing bits of Massachusetts, Long Island, and New Jersey is my homeland. The blue area hanging over southern Ontario, especially covering the Niagara Peninsula and the Lake Erie shore is where my people went. I have to tell you that having been brought up on history books with maps like this showing, you know, Alexander conquering the world, Genghis Khan conquering Asia, and the Huns sweeping over Europe, etc., one takes a sneaking pride in seeing one’s ancestors made to look like invading hordes or infectious diseases.

The Puritan Connection

These New Jersey ancestors are fascinating. The first I heard about them was from my Aunt Norma, my father’s sister, who one evening told me that my Pettit forebears, before the Revolution, had owned a tavern outside of Trenton called The Dark Moon, famous for its low life clientele and cock fights. This was deliciously salacious considering how upright and proper, even staid, my father’s family had always seemed, especially, dare I say, my aunt.

Also somewhat surprising is the further fact that I am descended simultaneously from two 18th century New Jersey Pettit brothers, one through my grandfather Charles Herschel Glover and one through my grandmother, who bore the delightful name Bertha Ida Belle Pettit. My father’s middle name was Pettit. And, yes, it’s French. Though I am not clear when these Pettits arrived in England prior to coming to America.

They may have been French Huguenots, Protestants who fled from France to England beginning in the mid-1500s, the original Channel-crossing refugees (nowadays they would be waiting to get on a jet to Rwanda). They had Calvinist sympathies and blended well with the Puritans, the sober, down-dressing, non-conforming dissenters for whom the Church of England had not gone far enough in ridding itself of idolatrous Catholicism. Alternatively, they may not have been Huguenots. Genealogists have found people named le Petit living at Ardevora and Philleigh in Cornwall as far back as the 13th century. Nonetheless, they were Puritans at the time in question.

Thomas Pettit (1609-1668) of Saffron Walden, Essex, put his young family (his wife was pregnant) onto the ship Talbot on March, 1630, and, after three months at sea (that’s 90 days on a small sailing ship, crowded with 60 other passengers), they landed at Charleston (later Cambridge) on July 2, 1630. This was just 20 days after Winthrop’s Navy, ships laden with 1,000 Puritan settlers, landed at Salem. Pettit’s wife had her baby on board the Talbot as it lay in Charleston harbor, before she even set foot in America.

Pettit had had to borrow money for his passage from his brother-in-law, a wool cloth maker, a maker of “stays and pays,” as it was called. He indentured himself (i.e. sold himself) to the brother-in-law for three and a half years to work off the debt. But by 1638 he owned a house lot in Boston where the Capitol came to be built and next to the lot where John Hancock built his mansion.

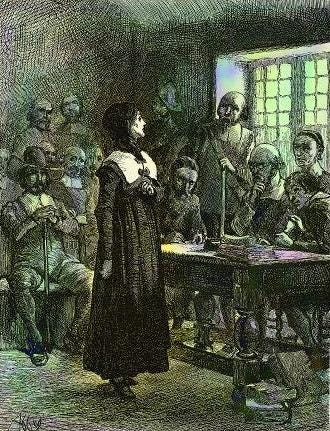

The Puritans had come to America in part to practice religious freedom. But they were a turbulent lot, squabbling amongst themselves about which freedoms they would allow. Some were expelled, others walked away to found new colonies. Roger Williams took his flock to Rhode Island. Thomas Hooker left his church in Cambridge to found Hartford, Connecticut. In April, 1638, Anne Hutchinson was arrested for her dissenting views. Thomas Pettit took her side and promptly found himself arrested for “slander, insubordination, and inciting to riot,” for which he was sentenced to 30 lashes and jail time. My sense is that he was not whipped, that all the accused were allowed to go free if they just left the colony within 10 days.

Pettit, inveterate dissenter and separator that he was, upped stakes and took his family to a new Puritan colony called Exeter, at the Falls of the Piscataqua in New Hampshire. These new refugees founded their own Congregationalist church and even signed a declaration of independence from the Massachusetts Bay colony. Pettit remained at Exeter for nearly two decades, had several children, and became a chief military officer and “inspector of staves” of the settlement. But the Boston Puritans kept up a relentless pressure on the wayward flock and eventually gained control of the land surrounding Exeter, which could only survive by reincorporating itself with the mother colony.

Thomas Pettit took his wife and eight children (other settlers came with them) and fled tyranny once more, this time finding land in Queens County on Long Island, where they named their new settlement, with typical Puritan flair, Newtown. It is now Elmhurst, between LaGuardia Airport and I-495.

In 1657, Pettit was elected town marshal replacing the previous office holder who had been voted out for improprieties in the pursuance of his duties. This caused some domestic havoc since Thomas Pettit’s son Nathaniel (1645-1718) had fallen in love with and married the previous marshal’s daughter. But then Thomas Pettit passed away in 1668, buried there where the jets thunder overhead all the day long.

He was my 7xgreat-grandfather.

New Jersey at Last and the Sussex County mixing bowl

In 1695, this lovestruck Nathaniel Pettit bought 100 acres in what became Trenton, New Jersey, at the junction of the Delaware River and Assunpink Creek, where the state capitol now stands. But then he seems to have gradually moved north to Hunterdon County. It’s not important to go through the various land transactions, which will bore you to death. In those days everyone was a land speculator, busy buying lands from the Indians and the trading them about amongst themselves.

He was my 6xgreat-grandfather.

He had several children, including a son also named Nathaniel Pettit (1676-1768), born on Long Island, dead at 92 in Hunterdon County, New Jersey. I think he was a carpenter by trade. This Nathaniel, too, had several children. Apparently, without smart phones and Internet, these people had a lot of time on their hands. Around 1749, his sons began to move north again into Sussex County, New Jersey, looking for land. But Nathaniel stayed behind (and I will leave him behind, because he is not very interesting).

He was my 5xgreat-grandfather.

But the next generation is fascinating.

Everyone, as I say, moved up to Sussex County and started founding towns and such on freshly surveyed Indian land. Other people moved in as well. The Greens, descended from the original land surveyor Samuel Green, the Moores, and the Glovers, whom I shall write about another time. Sussex County was, in effect, the genetic mixing bowl that resulted in great swathes of my family makeup, but also southwestern Ontario settlement history. These families intermarried before the American Revolution, then exploded with differential loyalties. Famously (in southern Ontario), a host of Greens, Glovers, Moores, and Pettits all migrated to the Grimsby area, along the Forty Mile Creek on the shore of Lake Ontario, as United Empire Loyalists, transplanting a bit of New Jersey in the new land. (See the Ancestry migration map above.) Others, of course, stayed behind.

Nathaniel’s sons, Charles (1730-1806, born in Trenton, died in Grimsby) and Jonathan (1721-1769, born in Trenton, died in Easton, PA), both turned out to be my grandfathers.

It has taken me ages to figure this out. My brain has frozen time after time. I will try to make it simple.

Charles Pettit had a son named John Charles Pettit, who had a son named Charles Pettit (1795-1877), who was my 2xgreat-grandfather and the direct ancestor of my father’s mother Bertha Ida Belle Pettit.

Meanwhile Jonathan Pettit had a daughter Dinah, who married a man named John Moore, and they had a daughter named Deborah who married Jacob Glover (born in Sussex County 1763, dead at Grimsby 1816). Jacob Glover, a Loyalist soldier in Lord Rawdon’s command during the Revolution, was my 3xgreat-grandfather, the direct ancestor of my father’s father Charles Herschel Glover.

All these people were part of the westward migration from Sussex County to Ontario. And for many, the Grimsby area by Lake Ontario was only a stopping place. As their ancestors had always done before, the Glovers, Pettits, and Moores hived off and moved again, ending up in Norfolk County where I was born.

My father described his family as Congregationalists, Puritan’s still, and like many of their forebears, they were farmers and carpenters.

The Dark Moon Tavern

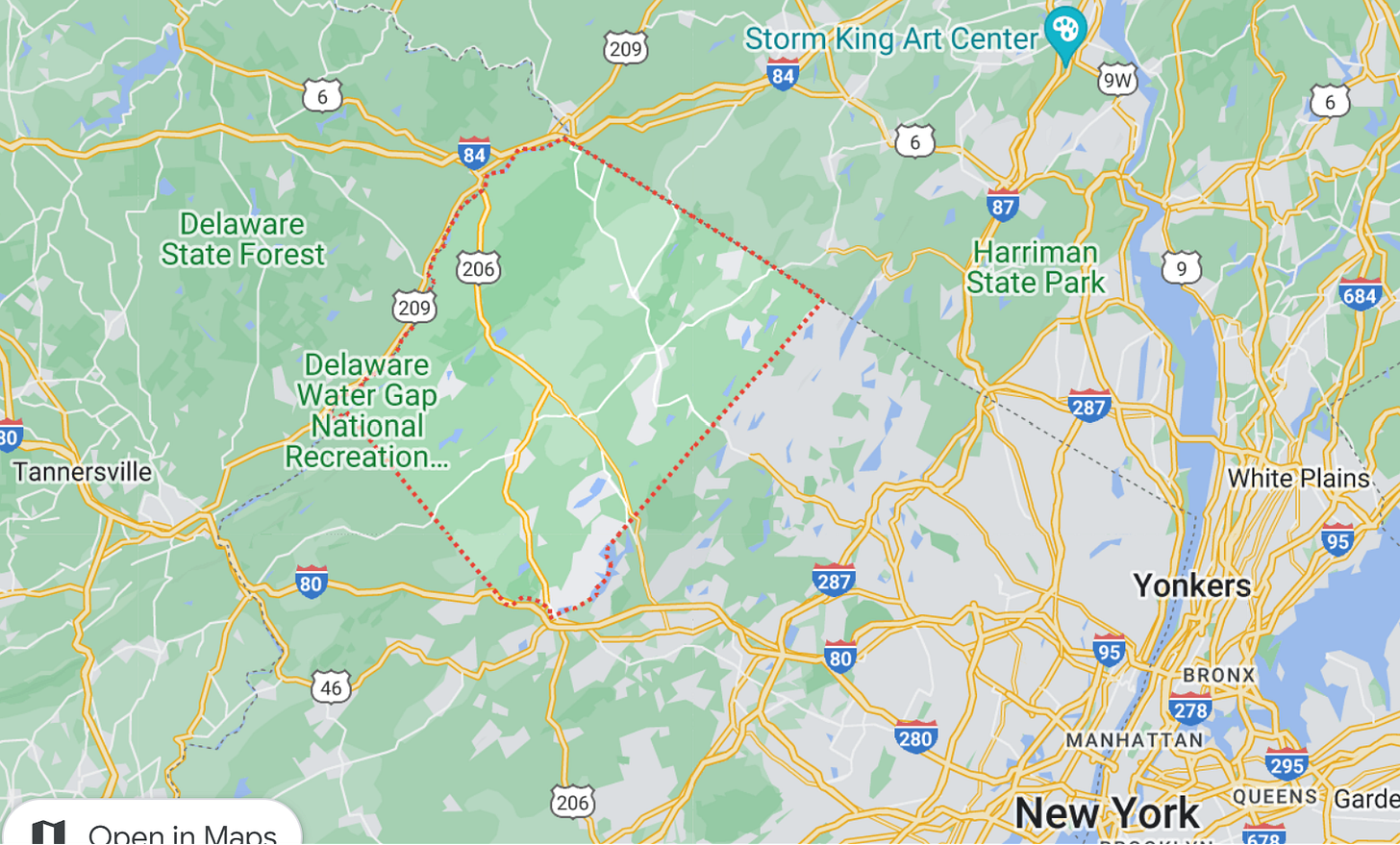

Jonathan Pettit’s Dark Moon Tavern was situated about a mile east of what is now Johnsonburg, between Blairstown and Stanhope, a patch of landscape the Native Americans thereabout called Pahuckquapath but which came to be known locally as Logg Gaol because of, well, the log jailhouse. Jonathan Pettit and a partner contracted to build the jail, and they were meant to add a court house as well, but opted to use the tavern instead. There was also a Dark Moon Road (Route 519) and a Dark Moon Burying Ground (now on private property). In the early 1750s, the hamlet of Logg Gaol was the Sussex County seat.

David Clark in his essay on the Green family, described Jonathan Pettit as “a vertically integrated entrepreneur who was judge, tavern keeper, stage stop-over administrator, and ‘motel’ owner.” My Aunt Norma told me that the tavern consisted of three buildings, two on one side of the road and one on the other to prevent total destruction if part of the tavern caught fire. Local historians think there were four or five buildings, Pettit adding houses as the need for accommodation and municipal services expanded. The original building was double-logged. Outside hung an old-fashioned swinging sign, a black crescent moon on a white ground.

Apparently, the jail was cheaply built, resulting in frequent escapes, despite being rebuilt and having watchman day and night. Many of the prisoners were in custody for debt. When they ran away, the county had to make good their creditors’ losses. The log jail was a money pit.

According to tradition, only one person was ever executed at the jail, a 25-year-old black woman hung for theft.

I leave it to the reader to imagine the understory here, the story of slaves, indentured servants, and the Native Americans pushed steadily from the land to make room for speculative capitalism on the march.

Courts were held at the tavern from November, 1753, to February, 1756. One of the first orders of business at the November 20, 1753, meeting was to hand out tavern licenses and fix the rates for services. (Remember, Jonathan Pettit was one of the judges.)

According to the New Jersey Herald,

As an example, a hot dinner that consisted of three dishes would be charged one shilling; a cold dinner was nine pence; a pint of wine was 18 pence; a quart of strong beer was five pence; or a gill of rum was three pence. Lodging for each person was set at three pence.

James P. Snell in his "History of Sussex County" (1881) wrote that "great inducements for wholesale lodging were also held out in those days, the charges being for one man in a bed, five pence, for two in a bed, three pence each and for three in a bed two pence each."

In addition were prices set for horses with oats per quart penny-half penny stabling horses, one shilling and pasturing horses, six pence.

Eventually, the taint of double-dealing caught up with Jonathan Pettit. In 1756, the Sussex County government and courts moved to Woolverton’s Tavern on the King’s Highway between Easton and New York. According to the Herald, “This move arose from disputes between County Freeholders and Jonathan Pettit, a surveyor and land speculator, who attempted to secure personal and economic benefit from locating the County Seat on his lands.”

Samuel Green, the original Sussex County surveyor, and his family lived in the village of Logg Gaol. During the Revolution, four of his five sons were actually imprisoned in the jail for being Loyalists. His daughter Rebekah Green worked as a bartender at the Dark Moon where (drumroll, please) she met and fell in love with a lonely widower (with young children) named Francis Glover, my 4xgreat-grandfather. The Jacob Glover mentioned above was his son by his earlier marriage. Rebekah Green became Jacob’s step-mother, so not genetically related to me, but when Jacob moved the family to Canada, she went with him, Francis having died.

Perhaps you are getting a sense of the dizzying permutations and combinations swirling around Logg Gaol and The Dark Moon Tavern in the mid-1700s and the curious mass migration of my genetic pod to Canada. And you can also see why I tend to think my roots truly lie in rural New Jersey under the sign of the dark moon (traditionally the three days of the waning crescent moon just as it switches to the new moon, also sometimes called the dead moon).

Epilogue

In early 2005 I gave a reading at Princeton University. A limousine picked me up at the Philadelphia airport. A cheerful, young black woman was driving. We got into a conversation and upon learning that she lived in Trenton, I launched into my song and dance about New Jersey roots and the Dark Moon Tavern. I said I’d love to visit Trenton some day. “Well, you’ve got time. I’ll drive fast,” she said, laughing, and careened off the thruway at the Trenton exit.

There followed a delightful tour of the downtown historic sights, the State House (on Nathaniel Pettit’s land), the Barracks Museum, the battle monument, and much more that I have forgotten, including the neighborhood where she lived. Frankly, I was far more impressed with her good natured generosity and sense of humor than with my ancestors’ contentious and grubby past (don’t you think?).

And I thought then, as I think now, that ancestor worship of the genealogical sort is well and good as long as memory doesn’t give way to false pride. The original Thomas Pettit came to America to live on his own terms, to escape tyranny in whatever form. I can almost admire his radical insistence, his constant removal, because it is principled (truly, I see some of my peripatetic self in him), if I can manage to avert my eyes from the genocidal catastrophe he participated in.

But later generations ceded principle to greed; you can follow the erosion of principle down through the family tree.

I feel terminally contradictory. I love these stories; I’m not sure I like the people.

And nowadays we all live under the sign of the dead moon.

Thanks, Doug. Great essay, and fun, yes, to see some of your qualities--the best and most independent ones--in these guys :). xo, Jody

Timely, dg - just as the double digit property tax increases are announced, one wonders whose hand is in whose pocket - love how you bring this to conclusion under the dark moon.