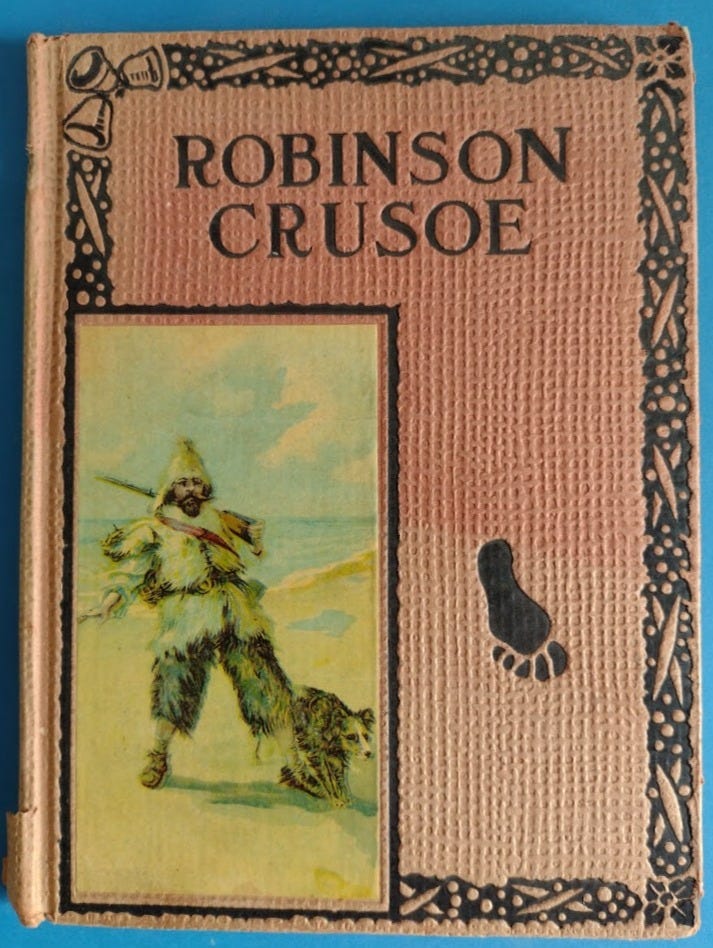

When I was a boy, my mother gave me an illustrated Robinson Crusoe, subtitled “Retold for Little Folk,” published by Charles E. Graham & Co. in New York (no date). It was a very thin book that had been given to my father when he was a boy. The cover shows Crusoe and his dog on the beach looking surprised. Crusoe is dressed in animal skins, more suited to the Arctic than the Caribbean. Next to the picture is the silhouette of a foot, Friday’s footprint in the sand. That footprint shows up in my novel Elle.

At the northern headland, where the island comes to a point like an arrow aimed downstream toward the Atlantic, the snow is scuffed and creased. Perhaps another vagrant seal has landed, I think. I kneel to make a closer investigation. Such is the power of the mind that initial assumptions can colour the evidence of our eyes. I think again, yes, a seal. But there, clear in the moonlight, is a left footprint and a right footprint, and they seem to walk about bipedally, which is fairly unusual for a seal (though, admittedly, my knowledge of seal lore is limited). They emerge from the water though, like a seal. But here I detect a long keel line in the snow. So, I say to myself, this seal arrived in a boat and walks around on his hind legs. I’ll wait. I’ll make an ambush. He’ll come back. We’ll eat like kings and queens.

Elle is delirious from cold and starvation, not to mention the fact that she is pregnant. She thinks the human footprints are a seal, which she can eat. Later, dragging herself along on frost-bitten feet, she follows the tracks, briefly seeing her encampment, the graves of her friends, and her hut through the stranger’s eyes (in keeping with the shape-changing theme of the novel). Eventually, she meets a native man named Itslk who lives with her for a while before wandering off again on his own. All this is an intentional parody of Robinson Crusoe and the man named Friday who begins their relationship by kneeling and placing Crusoe’s foot upon his head as an act of submission. It is a great imperial moment. Itslk is just the opposite. If anything, he dominates Elle; but for the most part, he doesn’t care much one way or another. “By the way, I don’t like to mention it, but you are so ugly it will be difficult to sleep with you.”

Here is Defoe’s footprint moment from the novel—no humor, no ironic inflection. A bit pompous.

It happen’d one Day about Noon going towards my Boat, I was exceedingly surpriz’d with the Print of a Man’s naked Foot on the Shore, which was very plain to be seen in the Sand: I stood like one Thunder-struck, or as if I had seen an Apparition; I listen’d, I look’d round me, I could hear nothing, nor see any Thing, I went up to a rising Ground to look farther, I went up the Shore and down the Shore, but it was all one, I could see no other Impression but that one, I went to it again to see if there were any more, and to observe if it might not be my Fancy; but there was no Room for that, for there was exactly the very Print of a Foot, Toes, Heel, and every Part of a Foot; how it came thither, I knew not, nor could in the least imagine.But after innumerable fluttering Thoughts, like a Man perfectly confus’d and out of my self, I came Home to my Fortification, not feeling, as we say, the Ground I went on, but terrify’d to the last Degree, looking behind me at every two or three Steps, mistaking every Bush and Tree, and fancying every Stump at a Distance to be a Man; nor is it possible to describe how many various Shapes a frighted Imagination represented Things to me in, how many wild Ideas were found every Moment in my Fancy, and what strange unaccountable Whimsies came into my Thoughts by the Way.

I can’t recall comprehensively, but I am not sure any of the critics noticed this fairly obvious literary reference when they wrote about Elle.

As a boy, I idolized Crusoe. He flooded my imagination. I prowled the woods with my dog, pretending to be shipwrecked, constructing huts and animal pens, lying in wait for cannibals. My little brother, skinny and pale, threw himself into the role of Friday with gusto. I was well into adulthood before I realized I'd only read part of the book, the child's version, the slave trading and sugar planting redacted. For example, this passage from the novel didn’t make it into Robinson Crusoe Retold for Little Folk. This is just a few pages on from the footprint scene and Crusoe is ruing the day he left his plantation in Brazil to fetch new slaves from Africa. His Original Sin, as he puts it, is not be content with what he had and the gradual growth of his sugar cane operation (as he says, he could have bought more slaves locally). In the time wasted on the island, he could have been

one of the most considerable Planters in the Brasils, nay, I am perswaded, that by the Improvements I had made, in that little Time I liv’d there, and the Encrease I should probably have made, if I had stay’d, I might have been worth an hundred thousand Moydors; and what Business had I to leave a settled Fortune, a well stock’d Plantation, improving and encreasing, to turn Supra-Cargo to Guinea, to fetch Negroes; when Patience and Time would have so encreas’d our Stock at Home, that we could have bought them at our own Door, from those whose Business it was to fetch them; and though it had cost us something more, yet the Difference of that Price was by no Means worth saving, at so great a Hazard.

Robinson Crusoe is part adventure story and part business novel, the first business novel ever written, a manual for the new rising middle class. Defoe invents the entrepreneur as a figure of romance, with all his talents and virtues, ingenuity, self-reliance, technical acumen, and his trust in bills of exchange. When I was young, it was universally marketed as the supreme role model for young people. Strangely enough, it still is.

Adaptation of the story of Robinson Crusoe for children. Relates how the shipwrecked sailor makes a new life for himself on the island, crafting shelter, food, and clothing for himself from the few tools he rescued from the ship and what he is able to find on the island. Living on the island for over twenty years before he is finally rescued, he reinvents almost everything necessary for daily sustenance. Suitable for ages 8 and up. 1

A shipwreck. A sole survivor, stranded on a deserted island. What could be more appealing to children than Robinson Crusoe’s amazing adventure? 2

For more than 270 years, readers everywhere have been fascinated by the young fool who ran away from wealth, security, and family for a rough life at sea and came to his senses too late, alone on a tropical island. Alone except for cannibals, that is, and God. Robinson Crusoe's adventure takes place on a remote island. Adjusting to the primitive conditions, he learns to make tools, shelters, bread, and clothes. More importantly, he becomes a Christian.3

Yet slaves and plantations saturate the narrative (not to mention loads of savages and cannibals). “The first thing I did,” says Crusoe, upon setting up shop in Brazil, “I bought me a Negro slave.”

So there I was, a southern Ontario farm boy unwittingly channeling a ruthless sugar magnate and slaver, the message loop so convoluted I still cannot completely wrap my mind around it. When that unlucky storm sinks Crusoe’s ship, he is sailing to Africa to buy slaves to populate his plantation — I didn’t read that part. This bifurcated mind, with its roots in ignorance or denial, is a characteristic of the slaving world. In the novel Crusoe speaks often of trust, as in one businessman trusting another, the basis of credit, but when a little boy helps him escape pirates, Crusoe promptly sells the boy.

The ur-businessman of English literature is competent, ingenious, able to use technology to bend nature to his will, loyal to his friends and business partners, and a slaver. Is this why we, as a culture both admire and fear the rich, the capitalists? We admire their ingenuity and capacity to organize technology and money, but we distrust their ultimate ethical allegiances. Jeff Bezos will build a giant super yacht while battling to keep wages down and prevent workers from forming unions in his warehouses. Robinson Crusoe redivivus.

I am not an advocate of book-banning, but it’s mysterious to me why the book banners don’t seem to have gone after Robinson Crusoe. Is it because the book has come to be thought of in many circles as the first modern novel, the seed out of which everything else grew? And if we ban it, erase it, we have to erase everything that grew from it? Do we have to erase ourselves? Do we really know who we are?

I ask this about myself. What effect did incorporating Crusoe into my boy-self have on me? I didn’t know about the slave part, but I surely knew about Friday and the foot-on-the-head incident (I think my brother actually enacted this—I can just barely call it to memory). And surely the slaves make Crusoe the man he is, even if they are absent in the pages I read. Later, I read the novel all the way through and saw it in a different light, with the slaves, killings, race-based betrayals, and imperialist memes, totally ripe for parody. But that’s two versions of my self: the one who saw himself as Robinson Crusoe and the adult version, still a work in progress.

Do we really know ourselves? How aware are we of the influences that shaped us?

As for Robinson Crusoe, and all the versions I possess, it’s a good book to keep around, reminding me to be wary of old certainties and versions of the truth, to be alert to influences I don’t suspect (what seems welcome, exciting, and easy is often the most insidious), and always, always, to strive to know myself and the world around me better.

Robinson Crusoe started out being a model for a little boy and ended up being the model of something else altogether.

Thank you once again for inspiring the writing part of my mind.

How we read and misread!