The furniture around the house where I grew up radiated messages. Every piece had a story. For my mother, each chair, table, ottoman, plate, or sideboard was a mnemonic device, a memory place inside her farmhouse memory palace. As a kid, I was bored and annoyed by all this and paid scant attention. Luckily, she had the prescience to hire someone with a video camera to come in and film her talking about her favourites. And eventually I started taking notes. But it’s not the same as having her here. Much has been lost, which is the nature of life. Sigh.

The McNeilledge serving table sits in a corner of the downstairs drawing room, called after its maker, a Scottish sea captain who settled in Port Dover on Lake Erie in 1829 and tried to become a farmer. He wasn’t very good at farming, so he left that to his wife and son and started sailing again. Restless, he produced a book of charts and sailing instructions—Sailing directions and remarks accompanied with a nautical chart of the north shore of Lake Erie (1848). Here is an extract from the book:

It used to be an old rule, in running for Port Dover in the night time, before the harbor or lighthouse was built, and it will be well to mention it here, in case of thick weather, &—let ut be ever so dark, steer west and keep your lead going, now and then, and strike hard bottom occasionally on your starboard hand; then haul off and get in muddy bottom, and keep so until you see the land right ahead; and when you think you are near enough by your own judgement, you can come to anchor in 2, 2 1/2, or 3 fathoms, and you will be at the anchorage a little above the harbor, with good holding ground.

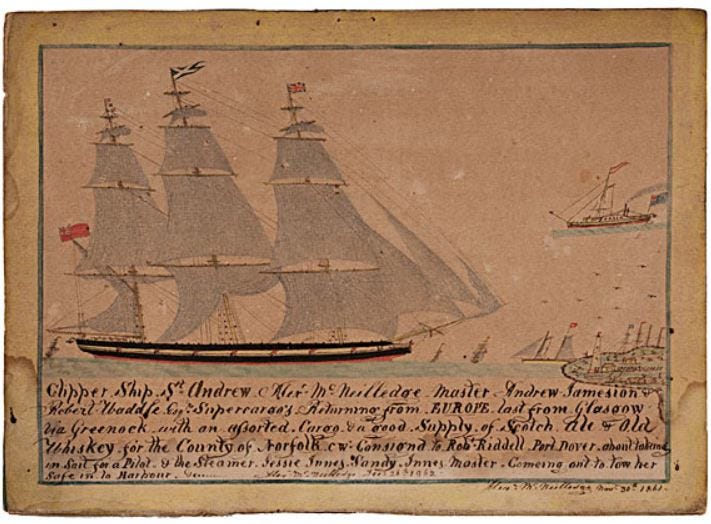

He drew and painted, curious text-art water colours of ships he had sailed on with little snippets of memoir underneath.

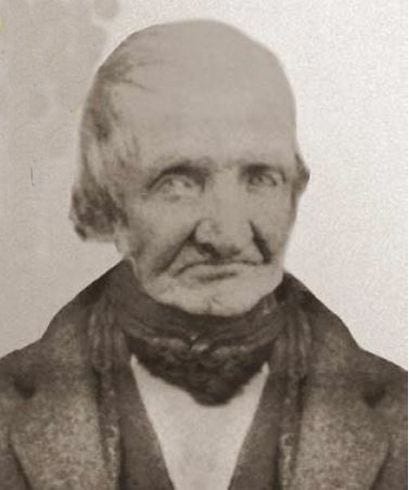

Then in 1873 at the age of 83, he wrote a last entry in his voluminous diary1, walked down into a ravine behind his house, and killed himself. That last entry read: “I last saw my mother on July 12, 1806, when I left Scotland expecting to be gone 3 or 4 months. I was shipwrecked, and did not return to Scotland for 40 years.” During the era when I ran the magazine Numéro Cinq, I published a poem about McNeilledge by my friend Karen Mulhallen. She begins with those lines from the diary, then limns the sad nostalgia of the expatriate Scots, shipwrecked, she writes, in a loghouse town by the lake.

They were all shipwrecks, maddened, these men,

gathered in that village in the wood, dreaming of prosperous towns,

perchance a great city, other civilizations…

McNeilledge made the table of cherry wood, with elegantly carved medallions and curlicues, not ornate or showy. The polished wood glows when the afternoon light hits it. It sends messages. As I run my fingers over the shapes, I can’t help but think about the man who created them. He was only eight years old when he shipped out of Greenock in 1806 on a ship captained by his father. He eventually became a captain himself, sailed around the world, fought off pirates, was shipwrecked, as he says. He married a Philadephia doctor’s daughter, Mary Ann Elizabeth Thum, in 1819. There is a painting of her at two, holding a bird, in a laced-trimmed white mobcap, with a necklace bearing the initials "ME" on the pendant.

Chad Fraser, an author who knows more about McNeilledge than I do, wrote of those years:

His exploits are the stuff of seafaring legend: he first went to sea as a cabin boy at the age of eight, was shipwrecked on Long Island in 1807, saw the Duke of Wellington in Lisbon, and even caught a glimpse of Napoleon Bonaparte, the deposed emperor of France, in exile on the island of St. Helena in 1817. Even what he might have considered the more humdrum aspects of his time at sea are thrilling by modern standards. The captain covered huge swaths of the globe, sailing to ports as far afield as China and running a naval blockade off Buenos Aires. And, for good measure, he endured robbery and plunder at the hands of pirates on the storied Spanish Main.2

Eventually, he let his brother Colin convince him to leave the sea and settle in Port Dover, where he started out working as a bookkeeper for Colin, which must have been a terrible comedown for an adventurous man in his thirties used to the great trading ports of Europe, America, and the Far East. Within a few years, he had bought a farm north of the village. He called it Greenock after the place where he was born. In his diary, he called his wife “Mrs Mc”. He had a dog named Watch.

My mother bought the table at an estate sale in 1951. There’s even a story about that. I think of my mother and her mother, Kathleen (Brock) Ross3, as a pair of estate sale rottweilers. On this occasion, they showed up together at a sale at Lulu (or Loula--I seem to have spelled it different ways in my notes) Jackson's house on Colborne Street in Simcoe. Somehow my mother had gotten wind of the McNeilledge table. I don't know what made her so determined to buy it (I wish I had her here to ask). But in 1951, my brother Rodger was still a baby, so she was stealing time away from him just to be there. The sale was open air, buyers and kibitzers standing on the lawn in front of the veranda, where each item was displayed in turn. The day wore on, the hours stretched uncomfortably, and finally my mother was forced to leave. But she gave my grandmother strict instructions about the table. It was the last item brought out onto the veranda. The auctioneer called out, "Who will give me $10?” My grandmother shot up, made a pre-emptive bid of $25, and took the table home. As my mother said, "No one bid against her--very few people ever bid against Nonnie."

In my notes, I see that my mother remembered McNeilledge4 as “a celestial navigator.”5

The diary is housed at the Norfolk Historical Society Archives in the Eva Brook Donly Museum in Simcoe. #Update 1: Mary Caughill wrote to let me know that there are eight or nine McNeilledge ship paintings and two sets of diaries—ship journals from 1810-1829 and 20 diaries, 1836-1882.

Chad Fraser, Lake Erie Stories: Struggle and Survival on a Freshwater Ocean (Ontario, Canada: Dundurn Press, 2008), 10-11.

I wrote about Kathleen in an earlier newsletter. We always called her Nonnie; her friends called her Pete, her childhood nickname.

There is also a nice piece online about McNeilledge written by the Port Dover antique dealer Phil Ross.

There very best account of McNeilledge’s life I have found is John A. Bannister’s essay “Captain Alexander McNeilledge, 1791-1874” in Western Ontario Historical Notes, Vol. XXII, Spring 1966, No. 1. I only managed to find a copy after I had finished writing this newsletter.

I love all the different sides of this story! And no sweat on the photography: the table looks regularly dusted and that’s quite an achievement in my book.

The woman who did most of the dusting in my mother's later years is a family friend. She actually mentioned on Facebook that she thought she might have dusted that table a thousand times. So you are very perceptive.