Back to the Mount Rich Estate on Grenada

For this trip to Grenada, I had both too much and too little information. I am still untangling the strands of what I thought before I arrived on the island, what I saw, what I thought I saw, what I had known before (from research and books), and what I had already forgotten. My intention for the trip was just to be there, to stand and smell the air, and see how the land rose and fell around me, the shape of the hills and the vegetation, see the people, listen to their voices. I did all that, but mostly this put me in a state of overload. I was constantly trying to register, write down, and assimilate impressions, comparing them with what I remembered from the books I had read. Sometimes they came together nicely; sometimes there were vast gaps.

A case in point: Bushwhacking up the cocoa-shaded hill above the estate ruins at Mount Rich, I found a gorgeous geological bowl, symmetrical and flat-bottomed, filled with more cocoa. I wandered around inside, then followed a path along the rim above. I met a man up there, in uniform (rubber boots, sack over his shoulder, cutlass in his hand), who told me the bowl was called “the lick” by the elderly people, that he could remember that in rainy season it would fill with water over his head, that there were stories of a tunnel that carried water out of the bowl (somewhere). It was only later, just now, that I looked at a map provided by MYCEDO (The Mt. Rich Youth, Cultural, and Environmental Development Organization) and saw where they had this feature on their village tour. They call it the Punch Bowl. I had forgotten about this map. Now, of course, I have to go back; I have 89 questions to ask.

Part of the reason I forgot this map was because I was thinking all the while of yet another half-remembered map from my research. This one showed an “estate house” located somewhere up that hill behind the estate works. Very vague. But I had intended to walk up the hill and wander back and forth, quartering the ground so to speak, and perhaps stumble on some ruins. That memory map got in front of the other memory map. And, I console myself, the whole idea of being there was just to experience it, to gain that sort of knowledge, fumbling, immediate, impressionistic, complex and multiple.

Another case in point: All of Mount Rich, the village and the old sugar estate, sits in a much larger volcanic bowl, subdivided by the St Patrick River, which separates the contemporary village proper from the estate ruins and modern cricket ground (which, according to land sale documents from the 1960s, was the location of the former slave village — the actual term used in those documents is inappropriate these days). The main road leads down to the village from the former Hermitage Estate to the south and then north toward Sauteurs on the coast. The vegetation is dense jungle-like with vines, brilliant flowers, palms, mango, and lots of cocoa and nutmeg.

I had looked at (and mostly misremembered) old maps with now disappeared roads. There is a modern concrete road that leads up from the main road, past the Kent House, and then up along a ridge, the height land, before stopping after perhaps a mile or so. I thought there was a ghost road that led from this concrete road, across country and back to Hermitage and set off to find it. It was a wonderful hike. I am not sure I have ever felt so safe as I did in Grenada. I was completely alone on these bush trails (not hiking trails), the sun was hot, but up along the ridges there was always a slight breeze off the ocean to the east. Along the way, there were patches of cultivated ground (not machine cultivated, but gardened) interspersed with overgrown patches and woods (which mostly were overgrown cocoa plantations).

In any event I was completely wrong about where I thought I was and where I thought I was going. Such a pleasure to be lost and blissfully uncaring, because everything I looked at was new and exciting anyway. Eventually, I came to the end of the path I was on, the edge of a bluff. I have a video of the moment. I was puzzled and disappointed of my intention, but knew there would be other days. Now, weeks later, I can look at the map and see where I actually got to (thanks to GPS location data on my photos). I was totally wrong about getting to Hermitage. I was actually on my way to another former estate called Mt. Rose. And the truth is I almost got there. Had I nosed around I am sure I would have found a trail going down to the east and would soon have hit the outskirts of that village.

I suppose some might find my map myopia and confusion ridiculous, but the truth was I enjoyed it immensely. After all the months and years of research, I was actually in situ, confused because there were trees all around and partial views, nothing like the clearly marked abstractions of road, rivers, and contour lines. I was figuring things out by feel and not by reading (not that I am against reading — I very clearly had a sense of what I was looking for and that helped me make sense (gradually) of what I was seeing. The process was like thought itself. I could feel the thinking taking place as I ran out of trail and tried to remember what the maps said.

The Carib Stones

Enough about me wandering around. One of my secondary objectives in visiting Mt Rich was to see the famous Carib Stone. Secondary because it predates the era of slavery, which begins with the French arrival in 1649. The islands were inhabited by indigenous people rather late. You know the story. People crossed the Bering Sea (next to Alaska) from Siberia to North America between 12,000 and 20,000 years ago (there are contested archaeological sites that push occupation back even farther — contested as in they are still going through the process of dating and debate that eventually discounts or authenticates a scientific observation). Within the last couple of thousand years, adventurous sea-going people began to shoot out of the vast Orinoco River delta on the shoulder of South America and explore the arc of islands from Trinidad to Cuba. Archaeology keeps evolving different narratives and sequences of occupation. And different population waves coming at different times represented different peoples and cultures. Columbus, the first European to arrive, confused everything by calling the people he met Caribs, who, he decided, were cannibals and best dealt with by turning them into slaves or killing them.

They weren’t Caribs. They were probably not just one people. The people who came mostly to be identified as Caribs called themselves Kalinago (with a branch called the Kalina). Both Kalinago and Kalina were living on Grenada when the French arrived. The French, beginning with their first settlement at St. George’s in the south, gradually pushed the Kalinago off the island. There is a famous story about the last of the Carib warriors jumping off a cliff at Sauteurs (Leapers) in the north to escape approaching French soldiers. This is folklore, though probably there was a skirmish and massacre, one of many. The expulsion of the Kalinago didn’t depend on one dramatic (and romantic) event. But eventually they were gone (the ones who could are thought to have escaped to other islands), though some Grenadians still claim genetic links. By the time the British took the island in 1763, the place had been ethnically cleansed for decades.

But the indigenes left evidence of their material culture. The climate is not conducive to preserving biological remains, wood, textiles, and bodies. As in many places in the Americas, archaeologists depend on stone tools and pottery to identify peoples and cultural horizons. Most of the productive excavations on Grenada are located around the coastal rim where the people fished, farmed, and traded with other islands. In the case of the older settlements, it doesn’t quite make sense to say they were Kalinago (just as a modern English woman or man is not a Celt or an Angle or a Viking). But people were continuously resident, whoever they were, and the most spectacular things they left behind are their petroglyphs, carved stones that dot the islands.

Mount Rich is unusual if not unique in being so far inland and in having both petroglyphs and a native village site, only recently excavated (superficially). I tried to visit the archaeological site. It is out on the Mt Reuil Road, a road heading north from the village toward a neighbouring plantation. This meant asking people in their houses if they remembered where any recent digging had taken place. One man pointed to the lot adjacent to his house and said they had dug in his garden. I went to look and found, yes, his garden. So much for the glory of archaeology.

I did find the main Carib Stone. I walked out along the road to Sauteurs, beside the ravine where the tiny St Patrick River trickles, until I came to the diminutive interpretation center and overlook. This was closed, but I could peek over the edge of the ravine and see the stone below. Not very satisfying.

I walked back to the village, crossed the bridge, and stopped to reflect. There was no way I could climb down the cliff behind the official overlook (about 30 or 40 feet), but the opposite bank looked doable. I decided to strike off through the woods, but right away discovered a little used path that ran to an equally disused old plantation road (it seemed to have been cobbled with stone at one time) that skirted the edge of the ravine and ran uphill at a slight angle. This in itself was exciting (and I am kicking myself now for not exploring it to the end).

I was able to scramble down the ravine from this road, little anoles rustling everywhere in the leaves at my feet. Once I grabbed a vine to steady myself and briefly caught the tail of one of these delightful creatures, much to our mutual surprise.

The main stone, the Carib Stone, though it is unlikely the historical Kalinago carved it, is as big as a tank, not easy to climb on to take pictures (so I didn’t try, not wishing to damage the strange, ghostly pictograms). They are a mix of faces, triangular designs (that look like star plots to me), and anthropoid creatures. One is a cat figure, the only one of its kind in the Caribbean — thought to be a memory drawing, recalling cats that lived in the Orinoco jungle where the ancestors of the people came from. They are eery, ghostly (partly because they are fading), reminding a person of a human intellect unlike our own.

There are theories but no conclusions about what these creatures are. Ghosts of ancestors, sacred animals, dreams, images of spirit travels, maps of an unknown universe. Nearby there are so-called workstones, covered with scooped out bowls, possibly for mixing shamanic potions (or something else entirely). These people left no stone structures, no other monuments (their wooden and thatch dwellings long gone). Even the location of the stones is ambiguous. It is fairly clear that the ones at the ravine bottom must have slid down from the hillside above at some point in the past. Indeed, Valerie Benjamin, the person who today owns the Mount Rich ruins and the land along the east bank of the river showed me an unpublicized stone in the woods along the lost road. It is smaller and far less worked than the stones in the river, and I could find only one clear face (even so, fading into the lichen). But I was touched as Valerie reminisced about coming here over the years by herself to sit, just sit, and watch that face.

And that made me think of the enslaved people who lived and worked just yards away, some of whose descendents no doubt still live here. How many little girls and boys had snuck off to look at the stones, climb over them exclaiming. Had those images from another world infected their brains, had they dreamed the dreams of those lost people, too?

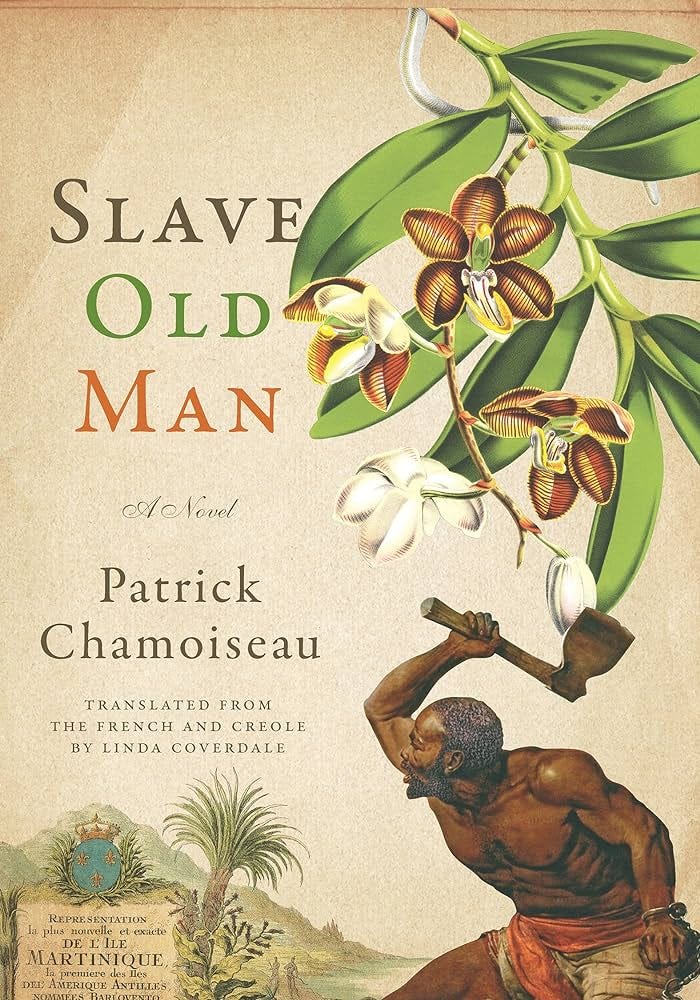

Slave Old Man — fusing the dreams

All the while I was looking at the Carib Stones, I was also thinking of a beautiful novel called Slave Old Man (1997) by the Martiniquan writer Patrick Chamoiseau. An elderly slave wakes up of a morning and in a moment of inspiration simply walks away into the woods, escaping, turning maroon. He is decrepit but determined. The master hunts him with a dog, a huge mastiff (the original French edition is called L'Esclave vieil homem et le molosse (The Old Slave and the Hound — or “big fierce dog,” according to the Collins dictionary). I won’t summarize. The chase is fierce and exciting and you will have to read the book yourselves to discover the incandescent moment when the dog and the slave collide. But the novel ends with a gorgeous prolepsis, a leap into the future, and the author (or authorial subject, the narrator) being informed of the discovery of a pile of ancient human bones at the foot of a Carib stone.

A volcanic rock. Imagining it astonishing. Covered with Amerindian signs. Guapoïdes. Saladoïdes. Calviny. Cayo. Suazey. Galibis. Every epoch jostling there together. I would have come upon it in some surprise. I had seen one in the forest of Montravail, in the commune of Sainte-Luce, but this one was doubtless in no way comparable. The Stone was supposedly in a deep ravine, way off on its own. Doubtless a ceremonial site. The vieux-nègre-bois spoke (to me or I don’t know whom) of another discovery. He had looked carefully around the Stone, doubtless seeking some of those treasures that harass our dreams. And he had found bones. Human bones. He showed me a sliver wrapped in oiled paper along with an old rosary. I saw it. I looked at it. I touched it in spite of his warnings about evil spells. He himself said he didn’t know why he was keeping that bone splinter. He had promoted it to a garde-corps de chance, a good-luck bodyguard. A relic to ward off misfortune.

I often went back to be near that stone. In dreams. Above those bones. In dreams. After distressing days my dreams go marooning. In these dreams, I lean back against the Stone. I contemplate the jumbled heap of bones. Who could that have been? A Carib. Doubtless. A Carib shaman who would have lived there, who would have engraved his memorial accounts and sunk himself into old age. Or the bones of a man wounded in initiatory fervor come to die in the sanctuary. My mind drifted like that around the Caribs. I imagined the bones. I saw them as eerie. Fossilized. No skull. A femur.

And then, after a few lines in which the author-narrator makes a leap, connecting the bones with the Old Man Slave, the runaway who disappeared into the bush and was chased by a dog, this finale.

The old slave had left me his bones, meaning: cartload of memories-histories-stories and eras gathered together. I imagined his last struggle, his ultimate huh of effort. That broken leg had dispelled his illusion about his run, pointing out (with a fearsome point) the clearing of his mind. They were warrior’s bones, says my so-genial brother. Of a warrior unconcerned with conquest or domination. Who would have been on the run toward another life. Of sharing and transformative exchanges. Of the world’s humanization in its wholeness. Doubtless possible. But my good fellow could also have quite simply run. A lovely run, completely meaningful in its very simple beauty, and thus open when touched by infinity. Very often, with the dream of that stone, musing on that tibia, I free myself from my militant concerns. I take the measure of the matter of bones. Neither dream, nor delirium, nor fanciful fiction: a vast detour that goes even to extremes to return to the combats of my age, bearing the unknown tablets of a new poetry. Brother, I shouldn’t have, but I touched the bones.

Astonishing photos! Did you ever read Wilson's Bowl.Phyllis Webb? Her poem about a similar bowl on Salt Spring Island.

Was intrigued by the pic of the Carib Stone in an earlier post so it is wonderful to read this detailed account here.

Completely relate to map myopia, confusion, partial views and figuring things out by feel.

Also, a beautifully written final paragraph by Chamoiseau (name roughly translates, maybe, to room of bird[s]), "bearing the unknown tablets of a new poetry".