Too White To Be of Use — Mary Mitchell & How She Won her Freedom

Out-take from work-in-progress

Below, you’ll find a short chapter from the nonfiction book I am writing about plantation slavery in the West Indies. I’ve had to trim this bit out of the book because it is slightly off-topic and because I have more germane material making the same point. My mantra these days is “focus & frame, focus & frame.”

The tiny island of Carriacou is part of the nation of Grenada, just off the coast of Venezuela. It was originally settled by various native migrations from the Orinoco region of South America. Then in 1649, the French came and drove out the natives. In 1763, France ceded the island to Britain (in the same treaty that gave Canada to Britain). Carriacou was a quiet backwater, settled by French planters, mostly growing cotton or indigo on small plantations using enslaved Africans as labour. Some of the landowners were mixed race, and there was a decent population of free black people as well. The British upgraded the island business model, consolidated estates (though some of the French and mixed-race planters stayed on), and began making money in earnest. Two large cotton estates called Craigston and Meldrum were owned by a Scottish family named Urquhart, absentee planters living in a castle in Scotland, while the estates were managed by, in 1809, the year I am writing about, a man named William Robertson.

Many of Robertson’s letters to his Urquhart employer survived in that castle where they were discovered and studied by an architectural historian named H. Gordon Slade1. One fascinating run of correspondence dealt with an overseer named George Mitchell who had a relationship with an enslaved woman on the estate, which resulted in the birth of two children. Legally, all children born to a slave mother automatically became slaves and were owned by the person who owned the mother. It didn’t matter if the father was white and free. Both Mitchell’s children were what were called in planter-talk “mulattoes.” The racial/genetic categories the planters used were quite precise. Mulattoes were the offspring of a white and a black parent. Mustees were the offspring of a mulatto and a white. A cabre was the offspring of a mulatto and a black. These categories generally had little to do with skin color and everything to do with parentage.

In 1806, George Mitchell began to lobby for the freedom of his enslaved son. But once the son was freed, the daughter, a girl named Mary, started a campaign for her own emancipation. Today, we have a pretty stereotypical view of slavery, and I don’t want to deny or mitigate the brutality and horror of that system, but when you study particular cases, you sometimes come up with surprises. The fact that this little girl began to pester William Robertson, and that he put up with it (given the violent options he had), and finally set her free (even offering to pay the going rate for her out of his own pocket), just amazed me. And then there is that strange line about her being too white to be of use; I could write a treatise on the position of mixed-race children on these plantations, neither one nor the other and not particularly trusted by either race.

These letters took months to go back and forth across the Atlantic, and in 1809, before Mary could be freed, George Mitchell died. But Robertson kept his word and let her go. For me, for a long time, that was the end of the story. I didn’t know what happened to Mary. And, of course, sadly, her mother remained nameless and a slave. But recently, in tracking down other formerly enslaved people, I have become a better detective. I think I know a good deal about what happened to Mary.

Read the chapter below, then I’ll tell you the sequel. It will shock and surprise you.

Too White To Be of Use — Mary Mitchell & How She Won her Freedom

I've already mentioned the correspondence between John Urquhart, the absentee owner of Craigston and Meldrum on Carriacou, and his manager William Roberston in connection with the Sister Incident in 1806. Now I want to go into another episode during Robertson’s tenure, one in which we get an unusual glimpse into the sexual relations between white men and female slaves. Once again this is sourced to the architectural historian H. Gordon Slade. He’s the one who found the documents and wrote them up, quoting letters at length. But as with the Sister Incident, I am looking at what he wrote with a different lens. I am only tangentially interested in Robertson or the Urquhart estates, but I am very interested in the sexual state of play between the overseer class and the slaves and the wave patterns they left in their wake in the form of lovers and children.

Robertson employed a white overseer named George Mitchell who had an enslaved partner and at least two mixed-race enslaved children. In a letter dated June 20, 1806 included a bill of sale for a mulatto boy. Robertson had given the child to Mitchell, who was his father, and freed him. As Slade notes, this was unusual. Children of slave mothers, regardless of who their father was, remained estate property. Children of slaves mothers were born into slavery. But in this case, Robertson adopted a benevolent policy, which he then carried forward.

Then, in November, 1809, he wrote a followup letter indicating that Mitchell also had a mulatto daughter and advised freeing her into Mitchell's hands as well. In fact, Robertson told Urquhart he would pay for the girl himself or buy a slave to replace her. The passage in question is fascinating in terms of what it says about race and slave-manager relations at the time.

Mary, a mulatto girl, and a daughter of Mr Mitchell's, attached to Meldrum estate seems to feel much that her brother is made free and that she is left a slave; she is of little use on the property and if you will have the goodness to dispose of her, I will give you credit for what she may be appraised for, or put a female slave in her place. I have had also several applications from the fathers of Jean, Mary and Peggy, twins and children of Betsy (Mutess) and of William, a son of Bess, a mulatto at Meldrum. They are all infants and are too white to be ever of any use to the properties, or very little, and if you will have the goodness to dispose of them I shall take care that their full value is paid.

It’s difficult to imagine why an estate manager would care or heed what a little slave girl thought except insofar as all these people lived together in a state of intense social intimacy with all the usual currents of fear, rebelliousness, affection, distrust, and resentment. Slaves were in constant contact with their white overseers, dependent upon them for food and medical care, for instruction as to work, permission to move about off the estate (to go to market or visit friends on other estates or hunt or fish); domestic slaves were in and out of the main house at all hours; it was more like a strange, extended family, not in any benign sense (not to discount the fact that these people were slaves in a relationship based on property ownership and violence), but in terms of closeness and interpersonal familiarity. So a cranky little girl might actually have had an impact.

Then there is a colour issue. Mixed-race children seem to have found themselves betwixt and between. In Grenada, there were so many mixed-race free men and women that the colonists enacted laws specifically to govern them, giving them a status above black slaves but not equal to whites in terms of land ownership and the ability to hold office in the government (but they were expected to fill the ranks of the local militia). This led to resentment because these mixed-race people were sometimes educated, some were even sent to Europe to study and then returned, and they felt themselves to be equal to whites. Julien Fédon, leader of the 1795 rebellion on Grenada, was a well-educated, French-speaking, mixed-race plantation owner.

Robertson’s statement that “she is of little use on the property” could refer to her age or the fact that being part-white she did not integrate well into the work force, either because she gave herself airs or because the other slaves were resentful of her colour and perhaps the special treatment she received (being the daughter of an overseer). Perhaps the best solution was to eliminate her from the slave gang — at another time, she might have been sold away.

Yet Robertson’s letter becomes even more interesting: besides Mitchell, other fathers wanted to buy their children out of slavery. It’s difficult to follow the grammar of the sentence but four children are mentioned by name: Jean, William, Mary, and Peggy. Mary and Peggy are twins and the daughters of a mustee woman named Betsy. Being a mustee, she herself was mixed-race, the daughter of a mulatto woman and a white man. William is the son of Bess, a mulatto woman at Meldrum. As in the case of George Mitchell’s daughter, the children are not deemed much use to the plantations partly because they are infants and partly because they are “too white to be ever of any use to the properties.” This situation does not seem to surprise Robertson; it cannot have been uncommon — and compares with the licentious chaos Thomas Thistlewood portrayed in his Jamaica diary2.

At any event, Robertson's singular act of benevolence in 1806 opened the floodgates in 1809, and he was content to find a way to free the children. A letter dated a month later, December 11, 1809, reports that George Mitchell has died but that Robertson intends to honour his deal in regard to all the mixed-race children.

I communicated to the Mulattoe Girl Mary, daughter of the late Mr Mitchell, Your humanity and generosity to her, in giving her her freedom. She is overjoyed poor Creature, and begs I will send you her Blessing; and permit me to add mine for the friendship you have shown to the Memory of the Deceased.

I shall inform the Fathers of the other Children that I have now your permission to dispose of them.

The enslaved mothers are not mentioned in these transactions; apparently, they remained slaves.

So what happened to Mary Mitchell?

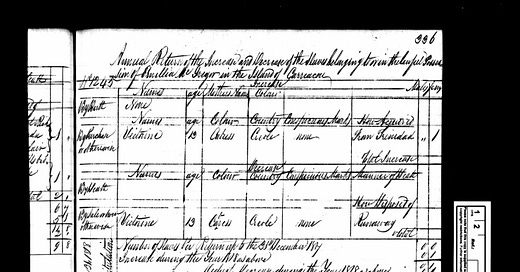

In 1817, the colonial government in Grenada began requiring planters and slave-owners to provide annual censuses of their human property, the so-called Slave Registry3. Censuses plus annual increase and decrease reports that recorded births, deaths, sales, purchases, and manumissions. These increase and decrease reports are especially useful because they tell you the names of mothers and their babies and also the causes of death when someone died. So from 1817 to 1834 you can somewhat arduously track individual enslaved people more or less efficiently (these records are all hand-written and the spelling of names is often approximate).

So in preparation for publishing this post, I looked up George Mitchell as a proprietor. By 1817, he had been dead for eight years, but he showed up as owning one male slave. The slave was “in the legal possession” of William Robertson, who was Mitchell’s executor. This tells you a lot. Robertson had taken over management of Mitchell’s affairs at his death. Mitchell had owned at least one slave, possibly more. The income that slave earned (you have to accept, unpalatable as it is, that slaves were income streams; slavery was the epitome of capitalism) probably went to Mitchell’s children.

I knew I was onto something with this little success. I started looking for Mary Mitchell, not among the enslaved people, but among the slave owners. And there she was. In 1817, she owned a 13-year-old black girl named Jenny. In 1818, Jenny had a baby boy named James, a mulatto. Thus at the end of 1818, Mary Mitchell owned two slaves, one of them fathered by a white man. After immersing myself in the world of plantation slavery for so long, nothing much shocks me. In this case, Jenny’s age did shock me. But the other part, buying a slave woman to produce slave babies, I had seen before. Sickening as it may seem, healthy women of child-bearing age were a good investment.

I have found other cases of former slaves owning slaves. Sometimes their motives were altruistic; they would buy family members in order to free them. I found one case of a woman who inherited her mother and didn’t get around to freeing her for half-a-dozen years (and the mother seemed to have filled out the paperwork). But in many cases, slaves were investment vehicles, income streams. It is entirely possible that George Mitchell set his children up with a slave or two of their own as a legacy (I have seen this pattern before).

Once again, we have a stereotyped image of the slave system, large properties, white owners, hundreds of enslaved people. But if you look at the Grenada and Carriacou indemnity list of 1835, when the West Indian slaves were emancipated, many, if not nearly half of the owners owned five or fewer people. Many owned just one or two. Some of these owners were mixed-race, some were even black.

In Mary’s case, she somehow acquired Jenny and Jenny immediately doubled the investment. But that wasn’t the end. Jenny kept on having babies, all mulatto, all belonging to Mary Mitchell. In 1834, she owned five females and one male, including Jenny, the mother. All were working on a small cotton estate called Experiment, owned by William Robertson, himself, by then, back in Scotland, an absentee planter.

There is a lot to gnaw on here, without jumping to quick conclusions. The story of Mary Mitchell is a daunting moral parable. Slavery was a totalizing system for those who lived within it. It wasn’t so much a matter of choosing a life course, as much as taking what was on offer and what everyone else was doing around you (most humans are morally lazy that way). In that light, former slaves owning and profiting from slaves is less surprising than at first glance. We tend to think that former slaves would have an automatic horror of the system that had oppressed them, and surely many did. Many became vehement and eloquent campaigners against the slave trade and the plantation system. Many also rebelled or ran away to live in maroon communities. Yet many found a way to work the system for their own benefit and survive within it. For the sake of future generations, just surviving was always the main priority.

H. Gordon Slade, 'Craigston and Meldrum Estates, Carriacou,1769-1841', Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 114 (1984), 481-537. See http://www.islandtrees.com/IMAGES/Craigston.pdf

https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/thomas-thistlewood-papers

Source Citation

The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Office of Registry of Colonial Slaves and Slave Compensation Commission: Records.

Source Information

Ancestry.com. Former British Colonial Dependencies, Slave Registers, 1813-1834 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

Original data: Office of Registry of Colonial Slaves and Slave Compensation Commission: Records; (The National Archives Microfilm Publication T71); Records created and inherited by HM Treasury; The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, Surrey, England.

good stuff man