Slavery was once legal in Canada. This became especially interesting during the American Revolution when masses of people descended from African ancestors surged across the border, some to freedom and some right back into chains. The British had offered freedom for any black person who joined the army to fight the rebels. A portion these were more or less safely settled in Nova Scotia after the war. But many white Loyalists, Americans who sided with the British, also owned slaves and brought them to Canada as part of their personal baggage. Not only that, but there was an active market in Montreal for slaves captured as booty by Indians and Loyalist guerillas raiding in upstate New York and elsewhere.

Checking my genealogy I found two New Jersey ancestors who owned slaves. Of course, I don’t kid myself; there may have been more. The details are brief and enigmatic, but Samuel Cooper Moore, who settled in Middlesex County, New Jersey, and died in 1688, owned three slaves at the time of his death: a 15-year-old boy valued at £29 and two girls valued at £20 and £22 respectively. He was my 7xgreat-grandfather. Captain John Moore (a different Moore family), my 4xgreat-grandfather, is said to have fled New Jersey after the Revolution by foot to the Mohawk Valley. He sent his family, portable property, and slaves ahead by bateau to Niagara, but when he arrived some time later, property and slaves had disappeared. According to New Jersey assessment records, my 5xgreat-uncle Captain John McCall owned one slave before he left for Canada. It seems he left that slave behind.

Am I proud of these forebears? No. Even before I learned about the slaves, I had complicated feelings about my Loyalist ancestors. Do I feel guilty? No. These things happened over a century and a half before I was born. Guilt without responsibility is an indulgence. It is facile and even immoral. But having this kind of story in one’s background comes with a duty of care. One must try to discover the facts and represent them accurately. That’s a long process. And one must try not to repeat the sins of our grandfathers in the present.

All this came as a surprise to me, but shouldn’t have. In the early 1790s, six of the sixteen members of the Upper Canada (Ontario) Legislative Assembly were slave owners. And New Jersey, where so many of my Loyalist forebears once lived, was a major slave state. Slavery began there during the original Dutch occupation, but increased substantially when the British took over and offered up to 150 acres of free land per slave for investors who brought their own workforce (this was aimed at planters in the West Indies). At one point, slaves in Bergen County made up close to 20% of the population.

After and even before the American Revolution, most northern states had passed laws to suppress slavery, some banning it outright and others adopting a gradual approach which began by stopping the importation of new slaves and by limiting the period of slavery. New York, for example, adopted the gradual approach in 1799 but completely outlawed slavery in 1827. New Jersey took its gradual approach seriously indeed. There were still life long slaves on the books as late as 1865 when slavery in New Jersey officially ended.

Upper Canada opted for the gradual approach, too. Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe arrived in 1792 and pressed for an outright ban, but had to contend with an entrenched body of powerful individuals who liked owning black servants. In 1793, just as in New York and New Jersey, a law of gradual emancipation was passed. No slaves were actually freed. No more new slaves could be brought into the country, but slaves already resident would continue to be slaves. Babies born to slave women were technically free, but had to live as slaves until they turned 25. Slaves could still be bought and sold, and there were no changes in regard to the severity of punishment for enslaved people. Still, this meant that slavery would eventually fade away. Thus Upper Canada could claim the honour of being the first British colony to ban slavery.

I was brought up thinking of Canada in sunny terms as the terminus of the Underground Railway, a refuge for escaped slaves. But the legislation of 1793 led to that situation in reverse, slaves in Canada running away to Michigan where slavery was outlawed when the territory was incorporated in 1805. So many Canadian slaves escaped to Michigan that by 1806 there were enough to form a black militia company for the defense of Detroit (against Canada).1

Such are the ironies of history.

As for Norfolk County, the first recorded slave is said to have been a woman named Aunt Molly who arrived with the Loyalist settler Lucas Dedrick in 1793. But this conflicts somewhat with a story E. A. Owen tells about the Bowlby family (also from New Jersey) in his Pioneer Sketches of Long Point Settlement. This concerns a woman named Dinah who came to Norfolk in 1796. I give Owen’s version:

It is said that Mr. Axford Thomas Bowlby's father-in-law was wealthy, and kept a number of colored servants, or slaves, as they were virtually at that time, and that he presented Mrs. Bowlby with one named Dinah. They brought this slave to Long Point with them, and it is said she was the first one of her race that came into the county. Before they left New Jersey, Dinah was as much the lawful property of Mrs. Bowlby as was the horses, and the cow that her father gave her, but if she came into Long Point settlement as such, she must have been smuggled in, for three years previous to this the new Legislature passed a law prohibiting the bringing in of any more slaves, and providing for the final extinction of slavery in the Province. In after years Dinah wanted to marry, and there being no one of her own color here she went to New Jersey, and married. After her husband's death she returned to her old place with Mr. Bowlby's family, and subsequently married a white man, who kept a tavern somewhere in the western part of the county. After her second marriage she used to say that her first husband was much the better man. Dinah was an expert cook and a neat housekeeper, and it is said the sight of a hair in the butter would completely destroy her appetite for two weeks.

Hendrick Nelles, the man on whom my novel The Life and Times of Captain N. is based, brought his family and five slaves when he finally settled in Canada after the Revolution. The date for this seems to be a moving target. Again, I quote Owen.

In the party were the six sons of Mr. Nelles Robert, William, John, Warner, Abraham and Peter and five slaves. They came up the Mohawk River in canoes, thence over a portage into Wood Creek, and again into the Oneida. Finally they crossed the Niagara River and took up their abode in the wilderness, where the old village of Grimsby was afterwards founded.

Aaron Culver, another New Jersey Loyalist2, brought a gang of slaves in the 1790s and settled where the town of Simcoe is today (somehow circumventing the law—though Lewis Brown, in A History of Simcoe, 1829-19293, says they were servants, not slaves).4 I won’t give you here the actual term Brown uses to describe these people because today it is deeply offensive when used by white people; the term “Darkeytown” is bad enough.

Culver is also a distant relation of mine. My genealogy software puts it this way: “son of the father (adoptive) of the wife of the 3xgreat-uncle of Douglas Glover.” This just about breaks my brain but means simply that his adopted sister was my aunt by marriage.

I must interject here my gratitude to Mary Caughill who, as a volunteer at the Eva Brook Donly Museum in Simcoe, sent me a copy of Scott Gillie’s article “Of Buttermilk and Banjos: A Glimpse into the History of Blacks in Norfolk County,”5 which gave me some valuable information and research leads. Gillies was at one time curator of the museum.

These servants or ex-slaves lived in cabins on Buttermilk Hill on the Culver farm, now part of the town of Simcoe. Through some sort of gradual emancipation, they were able to leave the farm by 1825 and settle in the neighborhood of Metcalfe and Head Streets, which became known as Darkeytown. These people formed a substantial community over time, probably absorbing fugitive newcomers from the United States. There may have been as many as 300 black people in Simcoe, close to one quarter of the entire population, by the mid 1800s. They had their own church, the British Methodist Episcopal Church on Chapel Street, established in the 1830s, and, briefly, after aggressive petitioning, their own separate school and teacher (though it had no playground or privy and the teacher didn’t make enough money to own a watch). On August 1, they would celebrate Emancipation Day a.k.a Wilberforce Day, the day the British Empire freed all its slaves in 1834.

Lewis Brown and Scott Gillies lean heavily on a singular document by a former Simcoe resident named Walter Matheson who returned from his home in Vancouver in 1919 to give a talk before the Norfolk Historical Society entitled “Darkest Simcoe Fifty Years Ago” which was printed in the May 22 Simcoe Reformer.6 Matheson’s piece is full of valuable information about the slave descendants living in Simcoe including several character sketches of prominent citizens who otherwise would be forgotten. Matheson is the person responsible for the population estimate of 300 (in 1853, he says). But his account is difficult to read today for his constant use of racist tropes and innuendo.7 For example, he’s the source for the “Darkeytown” term.

And what you get from reading all three is a sense threat and exclusion that was nearly constant for the black people of Norfolk. They petitioned for and built their own school in the early 1850s because, as Brown explained, “coloured children were not admitted to the common schools at that time” (though their parents paid school taxes). And they had their own church, according to Gillies, because “Blacks were known to enjoy more enthusiastic sermons and songs, and preferred a preacher whose customs and accent would be familiar to them. Because of these differences, the Black congregation was encouraged to worship separately.”

Much of this is depressingly familiar for anyone reading the daily news in any North American city today.

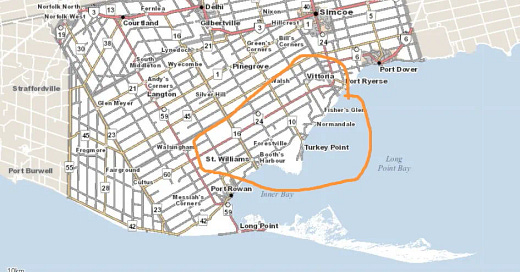

The first (and possibly only) person executed by hanging in Norfolk County was a black man, and the story is horrible. He was convicted of stealing from a store (yes, you could hang for that) and the execution was botched—he was still alive when placed in his coffin. E. A. Owen tells the story but gives no date except that it took place while Turkey Point was the judicial centre of the London District (so roughly between 1800 and 1815).

But there was one man hanged on Norfolk soil. It occurred when Turkey Point was headquarters for London District. The criminal was a negro, convicted of robbing a store an act which the law at that time made a felony, punishable by death. The store which was the scene of the robbery, was the second one in point of time started in Long Point Settlement. It was kept by one Cummings, and was located on William Culver's place known in modern times as the old Joseph Culver farm, near St. John's Church, south of Simcoe. After committing the crime, the negro tried to sell some of the stolen goods by peddling them among the settlers. The goods were easily identified, and this led to his arrest. He was tried, convicted and sentenced to be hanged, but before the day for execution arrived, he broke jail and escaped. Sheriff Bostwick offered a reward of $50 for his apprehension. A man named Robert Wood caught him in the cedars on Turkey Point, by first breaking his arm with a rifle shot. The sentence was suspended until he recovered from the effects of the wound. Joseph Kitchen was sergeant of the prison guards at Fort Norfolk at the time of this hanging. He saw the negro put into his coffin, and reported that he was alive when put there.

Matheson reports the murder of a young black man, David Deggs. No date given.

David Deggs, a particularly bright, industrious young man, was for years one of the landmarks at the Norfolk House under George Battersby regime. He was foully murdered by some young men in Brantford, his only offense being that he was a high spirited young fellow who stood up for his rights.

Through the 1860s, black people in Simcoe seem to have been subjected to harassment. Gillies quotes the Erie News of January, 1867.

On Wednesday evening of the last week the coloured residents of the town gave an exhibition in the BME church. The attendance was small, a fact to be regretted when it is to be considered that the object was to raise funds, to assist in paying their minister. The exhibition consisted mostly of recitations by children. To the discredit of our town we have to say the conduct of the audience was most disgraceful. There were several boys and men who had gone there with the intention of conducting themselves in the most rowdy-like manner and we must say that they were most successful in their efforts.

Two years later in 1869, the Erie News reported on another meeting at the BME Church. “A pleasant evening was spent, with the exception of the noise (to their shame, be it said), made by boys who ought to know better."

That same year, 1869, the Dominion Day celebrations in nearby Port Rowan opened with a procession of the Ku Klux Klan.

And until the end of the American Civil War, there was always the possibility that some agent, legal or otherwise, would reach into Canada and pluck a former slave back into the United States and servitude or worse. According to Brown, the Life Henry Tavern in Simcoe was known for being a haunt of slave hunters.

Coming down Young to the corner of Colborne, on the northwest corner stands a big frame hotel. The proprietor’s name is Life Henry and the hostelry was known as the Life Henry Tavern. Like all the old-timers was of quite large dimensions with the customary barn accommodation. It was at this place that the Americans used to have their headquarters when they came over to “kidnap n_____s” who were escaped slaves. While as we know, any citizens of Canada were free on Canadian soil, yet if they could be enticed back to the United States by any means, they would be taken back to their owners again. The practice was to come here, and when they found an escaped slave, invite him to the Henry Hotel, there fill him with liquor, take him to Port Dover and while in an intoxicated condition, put him on board ship and take him out on the lake. In these days just before the Civil War, there was a considerable traffic of this kind. While it caused a panic in our coloured colonies, of which Simcoe had quite a large one, it was very annoying and disgraceful to our white population.

Sometimes these “Yankee Sneaks” as they were called, would be mobbed. In fact the situation became so acute that often disturbances took place and the negro captives would be released from their captors before they could be taken from the shore.

This story does honour to those white people of Norfolk who helped disrupt the kidnappings (the sources don’t give details of the participants). And it parallels another case, a celebrated one involving a fugitive slave named Jack Burton a.k.a John Anderson. Burton and his wife and child were slaves on a plantation in the U.S. In 1853, his wife was sold to another plantation. Burton was caught trying to visit her, and, in escaping, killed one of his would-be captors. He made his way to Canada where he lived and worked under the name John Anderson until finally, in 1860, he was arrested in Simcoe. Legally, he faced a quick extradition to the U.S. and execution. The case aroused people in Simcoe to protest (a lawyer named Tisdale prominent among them). The county jail was surrounded, and the sheriff hastily moved Anderson to the Brantford jail to avoid civil unrest. One local historian, according to Scott Gillies, called this “a Canadian storming of the Bastille.”

The Anderson case, now a public cause, wound its way through the courts until extradition was finally approved. There were demonstrations in Toronto including a near riot outside Osgoode Hall. The provincial Attorney-General John A. Macdonald (yes, that John A. Macdonald) lent his support to the Anderson cause. Eventually, the decision went to the Appeals Court in London, England, where it was overturned and Anderson freed. Anderson subsequently emigrated to England (no doubt he felt safer there) where he wrote his own account of the case (remarkably, it was easy to find; you can read it here).

There is some credit to be given here to decent Canadians who stood up for what was right, even against their own legal system, but the general tenor of the story of black people in Norfolk County is a sorry thing. They settled in the county in large numbers from the outset, but history has virtually ignored them, heaping glory on the Loyalist pioneers instead. Both Gillies and Matheson couch their narratives in terms of progress, the situation for black people always improving (right up to that climactic Ku Klux Klan march). But this seems disingenuous. Gillies writes, “In the years following the Civil War, Norfolk's Black population began to dwindle. The reasons why are uncertain.” Another person might say the reasons are fairly obvious.

I’m indebted here to a chapter called “Upper Canada—Early Period” by William Renwick Riddell in The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 5, No. 3 (Jul., 1920), pp. 316-339. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2713625 Riddell’s contributions to The Journal of Negro History were subsequently published as a book, The Slave in Canada (1920), which is brilliant, painstakingly thorough, and fascinating to read.

In Lynnwood Park there is a marker commemorating Aaron Culver and pioneering role.

“Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe's visit to this locality in 1795 led to a grant to Aaron Culver, one of the districts earliest settlers, on condition of building mills. By 1812, a hamlet had formed near these mills, but they were burnt and adjacent houses looted by U.S. troops in 1814. In 1819-23, Culver laid out a village that he named "Simcoe," and a post office with this name was opened in 1829. Streets were surveyed in 1835-36, a courthouse and gaol built, and Simcoe was made the seat of the new Talbot District in 1837. Incorporated in 1849, Simcoe, with a population of about 1,600, became the county town of Norfolk County in 1850.”

You can read the entire book online for free at Hathitrust.

Here is what Lewis Brown says about Aaron Culver and his servants.

Over to the left, or northward and further back, is a group of cabins. It is a picturesque sight and typical of southern plantations. In these cabins live Aaron Culver’s colored servants. They are servants, remember, and not slaves, for notwithstanding the boasting of other countries as being the pioneers of the emancipation of the colored race, it will be noted by the record of the first sitting of the first Parliament of Upper Canada in 1703, presided over by John Graves Simcoe, our first Lieutenant-Governor, that they there passed an Act prohibiting slavery in the new province. And it has been pronounced by statesmen that it was the earliest legislation setting forth in clear, unmistakable terms that slavery would not be tolerated in this province of His Majesty.

So these were “free n_____s,” and of a summer evening you could stand in the valley and hear the banjos and listen to the singing of old plantation songs, just as you would in one of the southern states. This quarter at one time obtained the sobriquet of “Buttermilk Hill” because at times it was said this commodity figured prominently on the bill-of-fare. A few years later the colony migrated down to “Darkeytown” as the south end of Head and Metcalfe Streets was christened by the late W. C. Matheson. He called it “Darkeytown” in a pamphlet issued some years ago on the colored race in Simcoe.

Ontario Genealogical Society, Families (May, 2012) (You need to be a member to access it.)

You can read a partial transcript provided by my cousin John Cardiff on his massive Norfolk genealogy website. Blacks in 1860's Simcoe. This link brings up a double column list of sub-pages and you have to scroll down to the item “Blacks in 1860s Simcoe.” John died a year and a half ago leaving this site as a monument to his passion for the past. One hopes it will be supported long into the future.

Here is the opening of his talk for flavour.

To the valuable data accumulating in the archives of the Norfolk Historical Society, I desire to add a brief chapter concerning the colored residents of Simcoe half a century ago.

On this dark subject I may fairly claim familiarity, for I was born and lived for a third of a century just across the chromatic line that divided those of a more dusky hue from their Caucasian neighbors.

My recollections extend back to about 1853 at which time there were probably 300 colored souls in the town.

As children we mingled in play with the pickaninnies, regardless of the race color, or previous condition of servitude.

Thank you, Doug, for this detailed -- and sobering! -- wakeup call for Canadian Pollyannas such as myself. It's a deeply meaningful expression of what “duty of care” is all about.

This is very interesting, Doug. Thanks.