Death on the Mountain

My unfortunate Uncle William and his adventures in the Alps

This is a satellite family story. You know how it is. When you marry someone, you fuse two genealogies, which, if mapped on the page, look like butterfly wings stretching out, left and right, to infinity, or at least a couple or three generations. You not only fuse the genealogies but also the family stories.

One of the stories I heard growing up was about my great-uncle-in-law William Penhall who died in an avalanche on the Wetterhorn in the Swiss Alps in 1882 at the age of 23. William was born in Hastings, England, the son of a doctor. His younger brother Richmond Penhall immigrated to Canada in 1901 and settled in Port Dover. In Port Dover, he and his wife had a son named Douglas Penhall. The Glovers had a small cottage in Port Dover. At some point, Douglas Penhall met my father’s sister Norma; I imagine them eyeing each other on the beach and exchanging flirtatious small talk standing in Lake Erie. They married and Douglas Penhall became my uncle-in-law and his Uncle William, the unlucky mountaineer, became my grand uncle-in-law (or something like that).

One evening in 1987, Uncle Doug (when I was growing up I was called Little Doug and he was Big Doug) told me the kernel of the story. This is from my diary.

Doug started talking about his Uncle William who died at 23-4 in 1882, August, in an avalanche on the Matterhorn. He had been the first to climb a particular face of the Matterhorn and was studying medicine at St. Bartholomew's in London after graduating from Cambridge. There is a couloir named after him. D's parents married in 1890, his 3 brothers and sister were born in England and he was born here in 1906 (his birth registry has 1806 crossed out and corrected).

As usual, I didn’t pay too much attention to this story at the time, and, writing it down, I bungled some of the details. I was much more interested in another uncle who had come to Canada in the 1880s and joined the Northwest Mounted Police serving on the Prairies during the Metis and Cree rebellions. I tried to track him down, but the trail petered out quite quickly for lack of crucial information. His name, for example. But trying to trace his family background led me back to the story of Uncle William, the intrepid. I guess they were both intrepid. It was an intrepid, very English family.

I think I hadn’t quite believed Uncle Doug. I remembered reading about Edward Whymper conquering the Matterhorn as a kid. I even remembered snippets of that 1938 film The Challenge about Whymper and the Matterhorn. It was an amazingly awful story, a sign of the suicidal amateurishness of the early mountaineers. Whymper and his six friends and Swiss guides climbed tied together with thin rope (like a bell-cord someone said afterward) and long handled ice axes. They wore what we would call tweed sports jackets over sweaters, high woolen socks, and hob-nailed boots. They spent two sleepless nights on the climb, but did eventually get to the peak. One of the party, however, was a neophyte. He had never climbed before. Going up was fine, but he seems to have gotten spooked going down. One of the guides climbed below him, placing his feet on the ledges. The film shows this quite well. Nonetheless, they slipped, guide and young mountaineer. All seven were roped together. Two more fell, then the rope broke, which saved Whymper. (He was accused of cutting the rope, but later exonerated.) The four falling climbers didn’t die immediately. Whymper described seeing them sliding on the scree, holding their hands out to try to slow themselves. Then they disappeared one by one over a cliff face.

This was in July, 1865. Whymper wrote a book about it. This inaugurated what was called the first Golden Age of mountaineering. Uncle William, born in 1858 in Hastings, read Whymper’s book and caught the mountaineering bug. He liked the idea of being first, of conquering peaks and finding new ways up peaks. He was the son of a doctor. He went to one of those British public (private) schools and then to Cambridge University, graduating in 1881. He first climbed the Matterhorn in 1877 by Whymper’s northern route and was disgusted by the proliferation of fixed ropes, broken glass, sardine cans, and other climbing detritus. But in 1878, he was already competing with other climbers to bag untried climbs in the Alps. That year he and his party claimed the first ascent of the west face of Zinalrothorn.

Getting to the top of the Matterhorn meant climbing up ridges; they look like buttresses leaning up against the triangular faces. Between the ridges, the mountain was sheer rock cliffs and ice. Whymper took the north ridge in 1865, and the ridge on the south went the same year. The much more difficult Zmutt ridge on the west had yet to be climbed. In September, 1879, a man named Albert Mummery had assembled a team to tackle Zmutt (I know, I know: Mummery, Zmutt, and Whymper sound like I made up the names), but Uncle William Penhall, racing over from Cambridge and quickly hiring two Swiss guides, was simultaneously ready to ascend. Uncle William, just twenty years old, jumped in ahead of Mummery by a day and almost got up the Zmutt, but a barrier of icy rock teeth stymied him. Discouraged, he descended, meeting Mummery along the way, then turned around at 10pm and started climbing again. The next day, September 3, Mummery and his team, using ropes, scaled the teeth and pushed on up to the peak. But Uncle William was not to be defeated. While Mummery was going up the ridge, William had climbed to the right of the Zmutt and attacked icy cliffs straight on, a much more difficult route. Looking down from the ridge, Mummery could see him inching up the mountainside. William reached the peak a little over an hour after Mummery who had already begun the descent. Mummery had his first ascent up the Zmutt, and William had his own first by a different route.

This fierce, but gentlemanly competition is described by Stephen Venables in his book First Ascents. Please note the brandy, beer, and wine consumed by Mummery and his party.

His rival, William Penhall, was first on the ridge, getting to the top of a prominent row of pinnacles called “The Teeth” before retreating. A day later, Mummery arrived with his guide Alexander Burgener, to bivouac at the foot of the ridge. With their two assistant guides, they made a jolly party, enjoying “a heterogeneous mixture of red wine and marsala, bottled beer and cognac.” They set off long before dawn, climbing quickly to the Zmutt’s prominent snow ridge and over the jagged Teeth. Then they saw what had defeated Penhall – steep, smooth, slabs, veneered with verglas. Later Mummery described Burgener in action on this section: “It was obviously practicable but it was equally obvious that the slip of one meant the destruction of all who were roped to him.”

No-one slipped and the four men eventually completed the first ascent of the Zmutt Ridge. Looking across to their right, they saw Penhall in hot pursuit, climbing alone up the Matterhorn’s West Face – a truly futuristic route up a notoriously dangerous wall which has rarely been repeated.

For his feat, Uncle William had part of the mountain named after him, the Penhall Couloir.1

Four days later, on September 7, Mummery and Uncle William combined to make the first ascent of the Durrenhorn. Perhaps William had discovered he liked Mummery’s hard-partying style of mountain climbing.

William Penhall published his own account of the climb in an essay called “The Matterhorn from the Zmutt Glacier” in a contempory climbing magazine, Alpine Journal. As he makes clear in the essay, he wasn’t alone. He had two enthusiastic guides, Ferdinand Imseng and a local chamois hunter Louis Zurbrucken, and a porter. And though they didn’t get much sleep during their nights out, they did have time to brew some mulled wine. William and Imseng were wary of giving out too much information and tried to keep their plans for the ascent secret. They told the others that they were going chamois hunting, but the fact that they didn’t bring any guns gave their game away. On the 3rd of September, the day of the final climb, they could hear Mummery’s party to the left and above them.

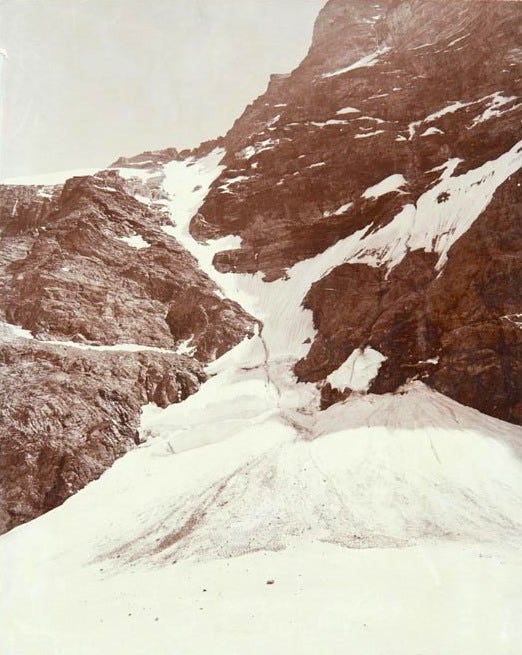

In August, 1882, Uncle William was back in the Alps (I simply don’t have any information about his adventures between 1879 and the summer of 1882) ready to conquer the Wetterhorn. As always, William seems to have been in a hurry. He arrived in the village of Grindelwald where he met up with a climbing friend, F. J. Church. They hired two guides, Andrea Maurer and Rudolf Kaufmann. Snow was forecast for the mountain in the coming days, and William decided not to waste a night sleeping while the weather closed in. He and Maurer left their hotel at about 1am on August 3rd. They were expected back that afternoon, but when they didn’t appear, search parties were organized for the next day. Some of their belongings were discovered at a climbing hut with tracks leading higher up, then disappearing. Later, their bodies were found, evidently crushed by an avalanche just below a ridge called the Willsgrat leading to the peak. William and Maurer were buried together in the village cemetery.2

I tell you all this because it’s a good story, not to draw conclusions. Uncle William was an enthusiast. Nowadays, he’d be jetting around the world to bag difficult technical climbs, still looking for firsts. Or he would be doing even less sensible things like base jumping. It was the peak of the Victorian era, the heyday of British imperialism. As a young English doctor-in-training of his race and time, the world was his to play in. The young mountaineers hired the Swiss villagers as guides and porters in much the way modern climbers use Sherpas to conquer Everest. It was fun, risky, and adventurous, but you sense the dark themes underneath.

I myself have no taste for this. I can confess to one regrettable incident when I attached myself to a small fir tree on a snowy ridge going up the Lions outside of Vancouver (really, I could see death on both sides of the trail, and it was the last tree, nothing but snow and rock ahead). I could not be persuaded to let go and carry on with the hike until a troup of middle school girls went skipping by and shamed me.

And, of course, there is that other regrettable incident when two friends and I attempted to climb Mount Marcy in the Adirondacks during a blizzard. I recall that my jeans froze solid over night, but we had whisky. When another climber tried to bunk down with us in the lean-to, my friends, worried about the whisky supply, sent him away into the snowy night.

Yes, one only has to think a little, and so many regrettable incidents come to mind. Mostly connected with snow and mountains.

Photo by Vittorio Sella and extracted from Andrew Smith Gallery Photography Auctions website. If the copyright holder objects, I will gladly take it down.

Most of this information comes from a post called appropriately “When things went terribly wrong in the early days of Alpinism” at SummitPost.org.

Adventure is such a seducer. The process of bravery unfolds over time. Great read. Thank you!

It seems your family is a bottomless trove of fascinating stories! Liked this one a lot. Hard to get my head around the courage/recklessness of such pioneers!