The map is not the territory

In which I cover myself with vainglory and misapprehension

One of my projects during my Grenada trip in the fall was to locate a small, land-locked cotton plantation called Industry on Carriacou. It doesn’t exist any more. Perhaps it has not existed since 1823, the year of the last data recorded at The Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery database. In 1823, there were ten women and five men living on the estate. As far as I can tell, they were all moved to Mount Rich, a sugar plantation on Grenada1, the following year, the land possibly absorbed into a neighboring estate.

There are no ruins marked on maps, the name is forgotten, and the town of Hillsborough has expanded upward toward the island spine obliterating whatever was once there in the way of buildings and fields. Not only that but the landscape is muffled under as blanket of coral vine or Mexican creeper, as it is sometimes called, an aggressive invasive species with distinctive bright pinkish-orange flowers that clings to trees, shrubs, stone ruins, and grave stones alike, making it very difficult to imagine what the place might have looked like when the land was under cultivation. The taxi driver who picked me up at the ferry terminal at Tyrrell Bay couldn’t remember the name but opined that the only way to kill it was to pave it over with concrete.

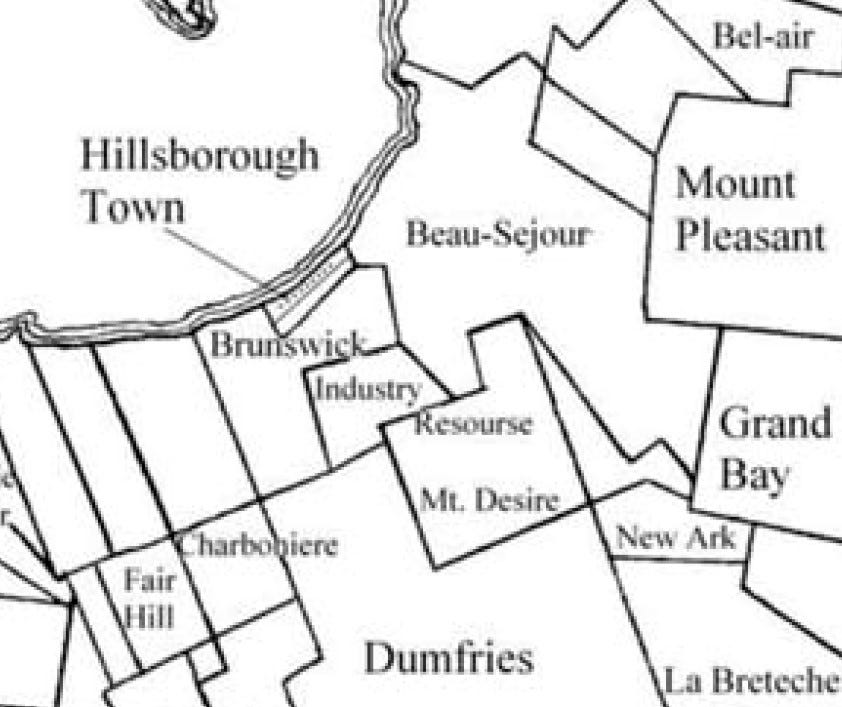

There is a 1756 census for Carriacou, when the island was still French, but I can’t match planter names to plantations. On Fenner’s map, thirty years later, Industry’s owner is marked as John Boyce. In a 1790 agricultural census, Boyce’s 56 enslaved people (with one white overseer) produced 7,000 pounds of cotton, or 125 pounds per slave. In comparison, the 554-acre Dumfries Estate, with 275 enslaved, produced 96,000 pounds of cotton, or 349 pounds per slave. Fenner’s 1784 map shows three buildings, an estate house and two other buildings for processing and storing cotton.2 The slave quarters have not been marked, it seems. The Fenner map also shows one of the island cart roads leading inland from Hillsborough, cutting straight across Brunswick Estate, then angling right (south) across a corner of Industry, and thence over the spine of the island to Dumfries and the Atlantic.

It has always seemed important that I pay attention to where these people lived and worked, that I be able at least to stand where they had stood and look out at the land the way they must have done, not just let them fade from memory.

On the other hand, my naivete always astounds me and I clearly didn’t anticipate the trouble I would have matching old maps to modern urban landscapes. In the end the only landscape marker I had was a curve in a road. As Alfred Korzybski famously observed, “The map is not the territory.” How could I forget that?

My first day on Carriacou, armed with the Fenner map, I stopped at the Museum (in an old cotton gin building, managed by a woman named Clemensia) on Patterson Street and asked what they thought of the lost Industry Estate. Straight up Patterson, I was told. Easy. I got distracted right away by some boys practicing soccer at the Hillsborough Recreation Ground. I sat in the bleachers and watched. They were the Hillsborough Secondary School team, preparing for a game against their snooty, better dressed rivals at the Bishops College Secondary School. What I thought about the kids I met along the way — always cheerful, open, delightful. Very much in the moment.

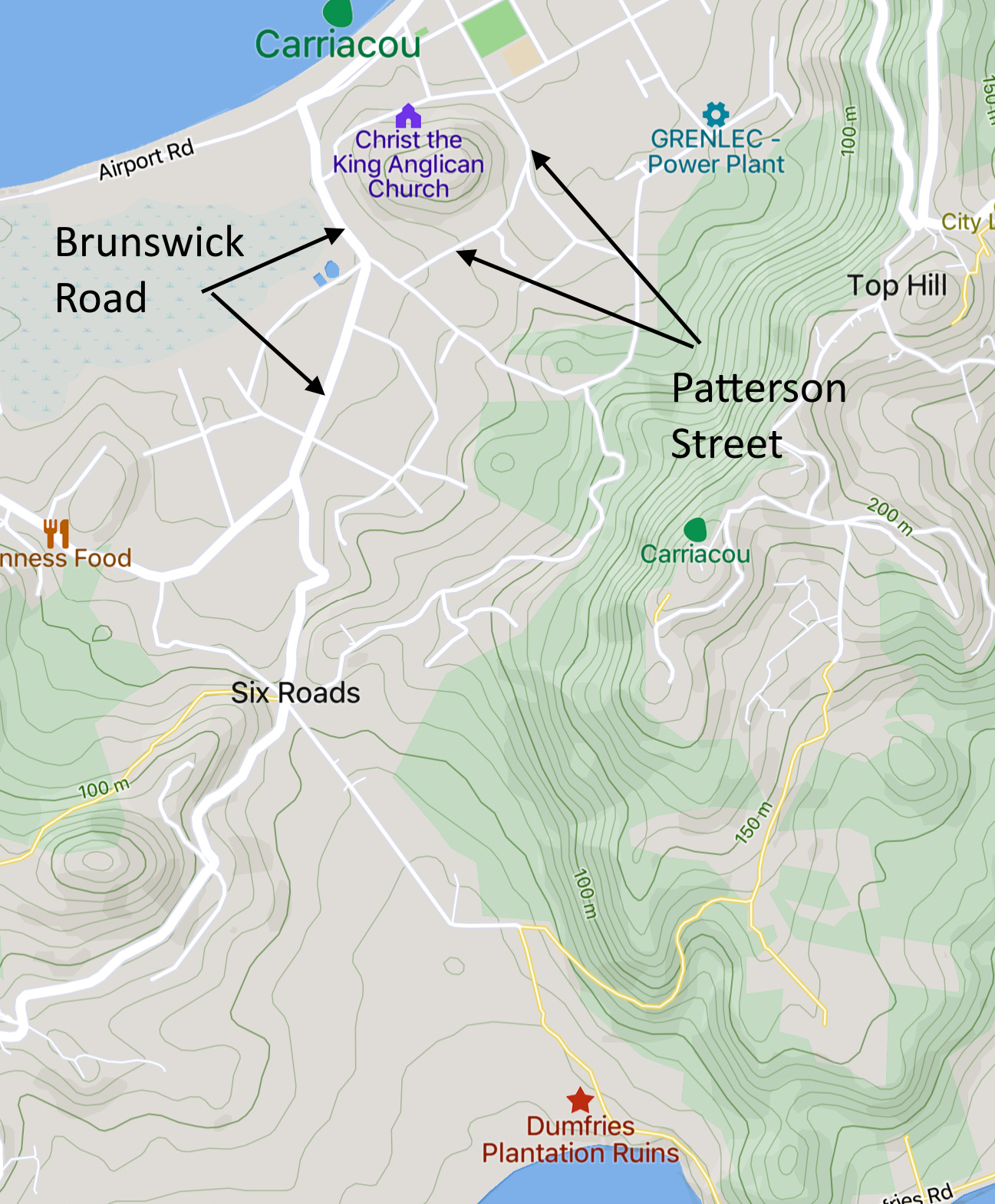

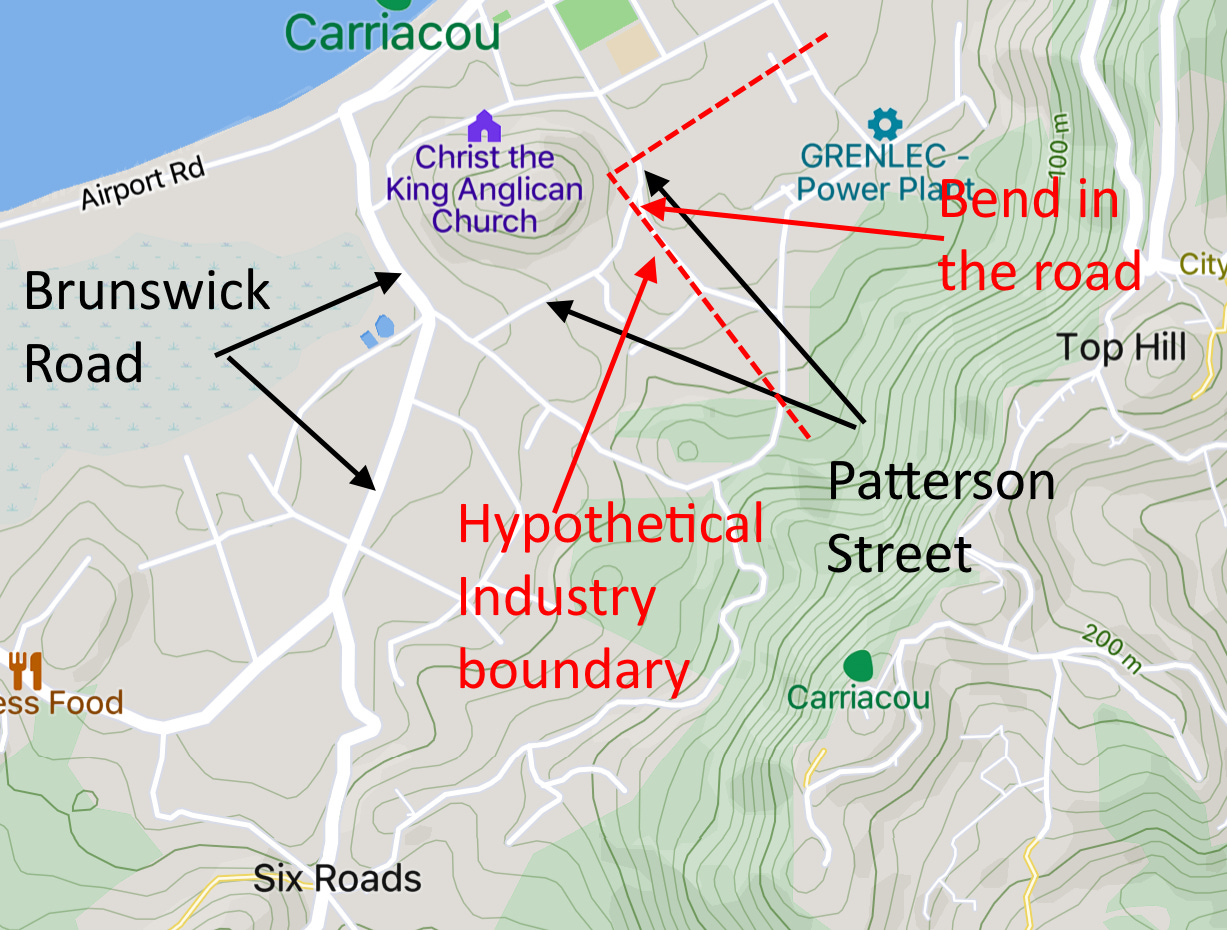

I kept studying the map and MapCarta on my phone and thinking that the shape of Patterson Street, where it angled to the right, matched the shape of the cart track on the 1784 map. I thought that angle must be the corner of Industry and that if I kept on going straight (there was a Y-junction) instead of turning, I would be walking along the southern boundary of the plantation. I convinced myself of this.

I followed to street (unnamed as far as I can tell), then took the first left and hiked over to the GRENLEC Power Plant. Very quiet along these roads except for stray goats and dogs. I spotted a man with tattoos working under his car. I said hi and by the way have you ever seen any ruins around here. My usual way of greeting people. He waved to the trash field next door and said the ruins were over there. He didn’t know what they were. He followed me into the brush, pointing out a crumbling wall, a broken lintel, and stone foundations disappearing under the coral vine.

The ruins of Industry, I told myself. Very pleased at my superior map-reading skills and archaeological intuition. I took videos of the coral vine and goat pastures, while congratulating myself on my success.

The next day I hiked north to Anse la Roche, putting Industry out of my mind temporarily, then the day after that I pushed up to the ridge that forms the spine of the island and walked along a dirt lane to Six Roads and thence to Dumfries, which was my goal for the day. But along the way I passed Dreddz Empire Bar and Garage3, stopped for a drink, and met Dredd, a.k.a. Andy Joseph, who also had a copy of the Fenner map tacked to the front of his bar. We crouched to examine his map, speculating on old roads and landscape shapes. Dredd thought I was wrong to assume that Patterson Street was the old cart track on the Fenner map. The cart track had obviously become Brunswick Road not Patterson Street. As soon as he said it, I knew he was right.

It seems obvious now, but when you’re standing on the ground, one curving bit of road looks much the same as another. The map is not the territory.

Hiking back to Hillsborough from Dumfries along the Brunswick Road, I watched the way the land changed. What was missing on the Fenner map were contour lines and elevations. The most striking landscape feature coming down from Six Roads corner into Hillsborough is the steep knob where the cemetery rises from the road with Christ the King Anglican Church behind.

It occurred to me that I ought to find the Anglican Rectory and inquire about real estate history. The Anglican Rectory was a secondary goal of my explorations. It figured prominently in the island’s history in the first two decades of the 19th century (and, yes, the resident clergyman owned slaves). There’s a phone number painted on a sign outside the church. It would have been easy to call, too easy for a man like me. I had seen the rectory marked on an oldish map on the main road leading north from Hillsborough, and the next day I walked over to investigate.

My diary notes read:

Started out a little after 9am up the road to the Anglican Rectory (which has some other name). Over-staffed, self-important place, with blue water jugs and stacks of toilet paper piled in a corner of the entry hall. I was sent downstairs to agriculture but went to the PR office by mistake. Nice guy who looked at my maps with me. Then he sent me to the permanent under-secretary or some such title who made me wait and then couldn’t help me. He said the old Anglican rectory was gone. It was over there — he pointed next door. Sent me to agriculture who didn’t know anything and agriculture sent me to town to the ratepayers office.

So bent was I on my mission that it did not occur to me until much later that this was not the Anglican Rectory, modern or otherwise. It was in the right location, but I had misread the sign outside.

Welcome to the Ministry of Carriacou & Petite Martinique Affairs.

Apparently, I am sometimes not so good at reading maps or signs. It is amazing I have managed to navigate life as far as I have.

I did walk over to the site of the old rectory building, now a gravel lot for cars and road maintenance equipment. I watched two iguanas, beautiful crested creatures, chasing each other in the sunlight.

But inflicting myself on the poor unsuspecting civil servants at the ministry (what a deceptive word, don’t you think?) gave me a chance to re-examine the map. If you look at a modern map there is a road — 2nd Avenue — cutting across near the boundary, dare one hope, of the Todd property and Brunswick Estate.

My last morning on Carriacou I took a final stab at pinpointing Industry. I turned up Church Street, just by the Tourism Office, all the way up to the junction with 2nd Avenue, the big hill in front of me and Christ the King Church just to my right. Then I swung right, past the church and over a spur, dropping down to Brunswick Road by the cemetery. Taking Brunswick east, I headed toward the landmark curve, the bright green mangroves of L’Esterre below and the serried gravestones marching up the knob on my left. I was now crossing the old Brunswick Estate.

When I reached the point at which Brunswick angles to the right, I was standing on Industry.

I took a photo of the eastern edge of the cemetery, a fence with a grassy lane going up, which I now take to be the actual boundary of the old Industry Estate.

I veered left at the Y-junction and followed Patterson Street, which circles around the knob and back to the Museum and the Hillsborough beach, quite sure that I was walking up the middle of Industry in a trough between the cemetery knob on my left and Top Hill and the island spine going up to my right. Overgrown fields climbed up the semi-forested hill but with some open pasture near the peak. All these trees must have been cut down when the plantations were in operation. And I noticed some small stone ruins, draped with coral vine, impossible to identify.

Okay, a bit OCD. Probably I am still wrong. And, for sure, I have no idea where the other boundaries might be drawn. It ought to be easy another time to find the Dumfries property line. I am calling that hill Cemetery Knob. I don’t know its real name. All my research has this ambivalent and haphazard character, though other plantations have been easier to find and explore. Industry is the one that fades even as I try to bring it back into focus.

But I look at the map now and think: In 1790, 56 enslaved people lived on this land growing cotton for John Boyce. In 1823, there were 15. Cotton linked these people and this land with the great textile mills of Manchester and the elegant English and Scottish country houses, all the thundering power of the Industrial Revolution and the elegant beneficiaries who thought very little of the source of their wealth.

The fact that these people were all moved to Mount Rich creates an interesting problem for genealogists tracing family roots. None of the people living at Industry remained on Carriacou. They have no descendants there. I do wonder if there are any families with roots at Mount Rich who also have a folk memory of having lived on Carriacou earlier. All in all, there might be quite a few of these.

The details of these censuses and much more can be found in Francis Kay Brinkley’s “An Analysis of the 1750 Carriacou Census” (Caribbean Quarterly, 1978) and David Beck Ryden’s "‘One of the Finest and Most Fruitful Spots in America’: An Analysis of Eighteenth-Century Carriacou” (Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 2013).

Dreddz Empire Bar & Garage

More about my trip to Grenada. Probably you’re tired of this, or thought I wouldn’t have anything more to say. This post is mostly photos but also about a man I met named Dredd, who shares my passion for the history of the place, the sad disrepair of graveyards, various animal encounters — just what happens when…

Fascinating and such fun to read!

These chronicles continue to intrigue, Doug. Thanks for them!