[God help me, this is turning into an epic. Since I published Three-Fingered Jack McCall, Part 1, I’ve had to expand and revise the entire California section of that post. And now it seems appropriate to cut this second section in two, so I can concentrate on the robbery in the final part. As many of you may already have discovered, it is often good to check the online version of my posts for revisions (also fixed typos and grammatical inerrancies). I realize most readers will not put up with this abuse, making you go back and forth and reread and then wait. Sigh. As some forgotten great writer once said, “So shoot me.”]

The wanderer, the sorrow & the pity

There are two kinds of wanderers. There are the authentic type of nomad, the desert Arabs of the Mideast and North Africa and the Roma, who travel light but carry everything — family, household goods, and livestock — with them. In effect, they carry their home place on their backs and never leave it. And then there are vagabonds of the west — adventurers, explorers, exiles, malcontents, escapists — who leave everything behind and start fresh in a new land, building a new home place just like the one they left behind. This is the type that colonized the Americas from Europe; also the template for my 5xgreat-uncle Hugh Percival McCall.

Having left his life in Norfolk County behind, he built another in Soquel, California, finding a wife, giving his children the family names. The irony is that he escaped one claustral pod only to construct another, much the same. The only things he carried with him were his restlessness, the desire to escape, to make a life with as little effort as possible, and a few primitive skills — chopping wood, shooting animals. He progressed from cutting down the stately ancient pines of Norfolk to cutting down the stately ancient redwoods of Santa Cruz. He crossed a continent, but never escaped.

Hugh Percival suffered what Baudelaire called “the Great Malady: Horror of One’s Home.” He was a throwback to our hunter-gatherer forebears, before farming, cities, and civilization. Yet wherever he went, he built a home. However you paper this over with talk of nomadism, romance, and adventure, such stories give off a strong odor of what used to be called male chauvinism but what I like to think of as gender thuggery. Bruce Chatwin spent his short life trying to write a masterpiece about nomads, whom he idolized. He failed to write that book, but wrote two wonderful spinoffs about wanderers, In Patagonia and The Songlines. In Patagonia weaves around the adventures of Chatwin’s grandmother’s eccentric cousin Charley Milward “the Sailor” who wrote in his scrapbook under the title This Freedom:

It is the man’s part to sow and ride away; conception is the woman’s office and that which she receives she tends to cherish and incorporate within her. Of her body that function is its glory; of her mind it is the millstone. A man rides away, a tent-dweller, an arab with a horse and the plains about him. Woman is a dweller in a city with a wall, a house-dweller, storing her possessions about her, abiding with them, not to be sundered from them.

No mention here of the detritus, those left behind, and the mutual responsibility for conception.

The irony of Chatwin’s book is how freighted it is with sadness and disappointment. Not happy at home, his wanderers rarely find any but the most fleeting happiness anywhere else. And most of them and their descendants live on in a wan afterlife struggling to preserve memories of home that inevitably fade.

The Madonna of Branciforte & her boy

Daniel McCall was born in Soquel in 1852, following his brothers Francisco and Juan (sons from an earlier marriage), the same year his parents were married. His mother, maiden name Dolores Moxica, descended from one of the original settlers in a secular pueblo called Branciforte just across the San Lorenzo River from the original Santa Cruz mission. Branciforte was founded in 1798 by eight petty criminals — courtesans, brawlers, syphilitics, small-time crooks — and their families shipped in by the authorities from Guadalajara. One of these originals was a carpenter named Jose Vincente Mojica who brought his wife and five children to the settlement. It’s fascinating to see the parallels — at precisely the same time the McCalls were cutting farms out of the forest in Norfolk County, the Mojicas were building huts on a bluff overlooking Monterey Bay. This Vincente Mojica was Dolores Moxica’s grandfather.

The colony failed to prosper; the settlers earned a reputation for laziness, lack of ambition, and lawlessness. There were gunfights, bullfights, and fandangos (and fandango girls). In 1818, threatened by pirates, the Franciscan brothers and neophytes (the name for their Indian converts) at the Santa Cruz mission, hastily fled inland for safety. The excellent people of Branciforte took advantage of their absence and pillaged the mission, even stealing, the story goes, the vestments off the saints statues.

According to my conjectural timeline, Hugh Percival turned up around 1833, and set to work cutting redwoods for the new sawmill on the Zayante Creek. Between 1840 and 45, he met and married a second wife (Anor Haviland, his first wife, was still alive, of course) who died after bearing him two sons. Then he somehow captured the heart of Dolores Moxica who was much younger, and, like Anor, unable to read and write. How this came about one can only conjecture; in later life Dolores seems to have been widely respected as a descendant of pioneers and a pious church-goer. But somehow she ended up with a wandering trapper turned lumberjack much advanced in years.

From 1850 on, censuses show them living in Soquel. In 1860, Hugh Pablo is 69; his wife is listed as 29; and he is farming in Soquel. In 1870, just before Hugh Pablo disappears, the household consists himself, Dolores, Santiago (James), 10, also illiterate, and the baby David, born in May. The rest had flown the coop, though Francisco marries and continues to live in Soquel. His brother Juan seems to have died; nothing more is heard from him. Francisco pops up in a voters list as a “a laborer”; in 1896, the Visalia Times describes him as an upright businessman in Santa Cruz managing a livery stable; in 1910, he is a “teamster.” Reading through the news reports following Dan McCall’s shooting, I get the sense that Dolores didn’t speak English, which means all her children were bilingual (even Hugh Pablo must have spoken some Spanish).

In March, 1896, Dan McCall was 43 years old. He had been married, but his wife had died (in 1894 or “several years ago,” depending on which newspaper you read) leaving him with one son, also named Daniel, 21. The Santa Cruz Penny Press of March 20 claimed he "always regarded as a decent, harmless, though not over bright fellow"…"just the man to be easily made a victim of.” A man named Arana who claimed to know Dan and who accompanied his two brothers to the burial in Visalia told the papers that Dan had shot and killed a man in a dispute over a land claim on the coast, but was subsequently discharged on the grounds of self-defense (no other person mentions this; Arana seems to have been a fund of negative stories). According to the Santa Cruz Daily Sentinal Dan McCall had been a member of the Santa Cruz Hook and Ladder Company and had competed in fireman tournaments. He had joined the Cleveland Club and supported Democrat Grover Cleveland for president. Until his death, he sent his mother money every month to pay her rent. Contradicting Arana’s story about the shooting, one anonymous acquaintance said Dan had nothing to do with guns and might even have been too timid to shoot one.

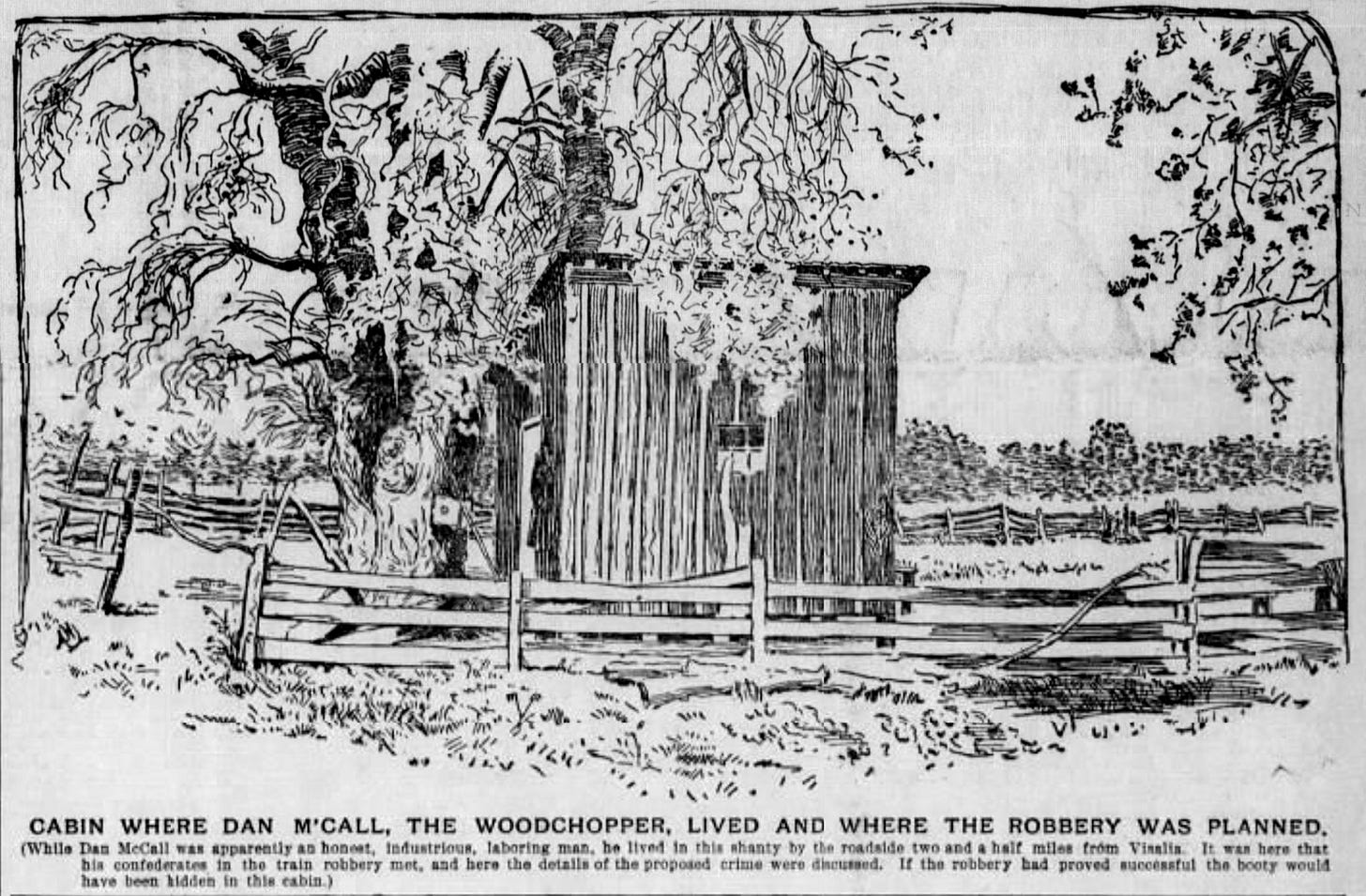

In recent years it seems he had fallen on hard times. I get the sense he was drinking too much. In conversation he could be a loud talker. He drifted away from Soquel picking up manual labor jobs. In 1888, he was living in Fresno. For the last four years of his life he was in Tulare County between Fresno and Bakersfield (the county contains most of Sequoia National Park and Sequoia National Forest). In 1895, he was chopping wood for a rancher named Ben Hicks, just north of Visalia in the San Joaquin Valley, scene of a series of famous train robberies and shootings. He made his town headquarters at a so-called deadfall saloon run by a man named Si Lovren on the corner of Main and Garden Street. In October 1895, he took on a partner, a 19-year-old newly arrived Texan named Obie Britt, and the two of them signed a fresh contract with Hicks. McCall had a small redwood shack on Hicks’s land, where he kept a rig and two horses.

He was five feet, eight and a half inches tall, with swarthy skin, brown eyes, and black hair. There were noticeable scars on his neck, as though from a fight. He wore elaborate side whiskers to cover the scar.

The Octopus & the Dalton Gang

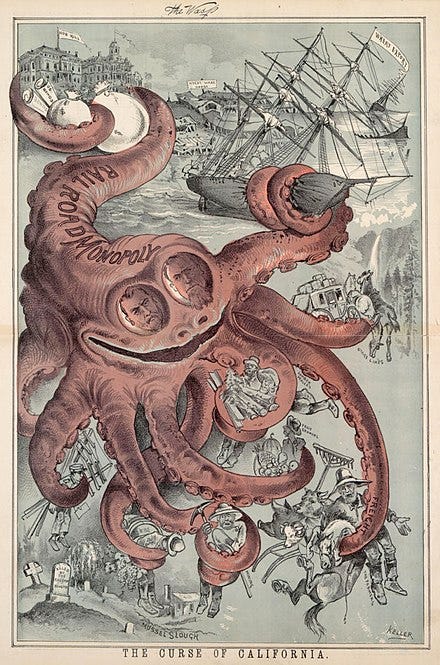

In 1882 The Wasp, a San Francisco satirical magazine (then edited by Ambrose Bierce), published a G. Frank Keller cartoon depicting the Southern Pacific Railroad monopoly as an octopus. In 1901 Frank Norris published his novel The Octopus, A Story of California, a bitterly realistic account of the struggles between ranchers, wheat farmers and the railroad monopoly in the San Joaquin Valley. Here’s a bit from the climactic shootout (based on the Mussel Slough Tragedy of 1880, when seven people were killed in a battle between sandlappers (settlers) and railroad men in the Valley.

But Cutter, Phelps, and the old man Dabney, misunderstanding what was happening, and seeing Osterman leave the ditch, had followed his example. All the Leaguers were now out of the ditch, and a little way down the road, Hooven, Osterman, Annixter, and Harran in front, Dabney, Phelps, and Cutter coming up from behind.

“Keep back, you,” cried the deputy again.

In the group around S. Behrman's buggy, Gethings and Delaney were yet quarrelling, and the angry debate between Magnus, Garnett, and the marshal still continued.

Till this moment, the real estate broker, Christian, had taken no part in the argument, but had kept himself in the rear of the buggy. Now, however, he pushed forward. There was but little room for him to pass, and, as he rode by the buggy, his horse scraped his flank against the hub of the wheel. The animal recoiled sharply, and, striking against Garnett, threw him to the ground. Delaney's horse stood between the buggy and the Leaguers gathered on the road in front of the ditch; the incident, indistinctly seen by them, was misinterpreted.

Garnett had not yet risen when Hooven raised a great shout:

“HOCH, DER KAISER! HOCH, DER VATERLAND!”

With the words, he dropped to one knee, and sighting his rifle carefully, fired into the group of men around the buggy.

Instantly the revolvers and rifles seemed to go off of themselves. Both sides, deputies and Leaguers, opened fire simultaneously. At first, it was nothing but a confused roar of explosions; then the roar lapsed to an irregular, quick succession of reports, shot leaping after shot; then a moment's silence, and, last of all, regular as clock-ticks, three shots at exact intervals. Then stillness.

Delaney, shot through the stomach, slid down from his horse, and, on his hands and knees, crawled from the road into the standing wheat. Christian fell backward from the saddle toward the buggy, and hung suspended in that position, his head and shoulders on the wheel, one stiff leg still across his saddle. Hooven, in attempting to rise from his kneeling position, received a rifle ball squarely in the throat, and rolled forward upon his face. Old Broderson, crying out, “Oh, they've shot me, boys,” staggered sideways, his head bent, his hands rigid at his sides, and fell into the ditch. Osterman, blood running from his mouth and nose, turned about and walked back. Presley helped him across the irrigating ditch and Osterman laid himself down, his head on his folded arms. Harran Derrick dropped where he stood, turning over on his face, and lay motionless, groaning terribly, a pool of blood forming under his stomach. The old man Dabney, silent as ever, received his death, speechless. He fell to his knees, got up again, fell once more, and died without a word. Annixter, instantly killed, fell his length to the ground, and lay without movement, just as he had fallen, one arm across his face.

This is essential background for what happened to Dan McCall. After gold was discovered and Mexico ceded California to the United States, settlers flooded the territory, young men looking for gold, desperately poor families, squatters, and rapacious capitalists who quickly scaled up a transportation infrastructure (shipping and railroads) supported by a federal government anxious to solidify its grip on the vast country and none too delicate about the fortunes the railway magnates scooped up while building the nation’s arteries. Typical of the California tycoons was Leland Stanford who came to Sacramento in 1856 and quickly established himself as a mega investor in land and railways. His rise was lightning fast. He became governor, head of the company that built the western section of the first transcontinental railway, founder of Stanford University, and a billionaire (in today’s money).

It was Stanford who claimed the honor of driving the last, golden spike (with a silver hammer) on May 10, 1869, incidentally providing Hugh Pablo McCall with an easy route home to Norfolk County in Canada the following year. It is especially instructive to set Stanford’s skyward trajectory next to Hugh Pablo’s stunted downward spiral. Stanford also supported the state’s genocidal policies against the Indians. I have not dwelt on the fate of the indigenous population in this essay; see my earlier piece on Aunt Hetty McInnes for the grisly details. If ever an institution was ripe for a name-change based on the systematic cruelties of its namesake, Stanford University is at the top of the list.

In order to get railways built both federal and state governments adopted a policy of giving out vast tracts of land to the railway companies to inspire their construction efforts (same as in Canada). This brought the railways into conflict with settlers who may have built farms on land they later discovered was not theirs (the railroads would offer to sell it back to them at “developed” prices they could never afford). In the San Joaquin Valley, the Southern Pacific also manipulated haulage rates, jacking up the rates when wheat farmers were desperate to get their crops to market. The railways had politicians, land speculators, and the law on their side (also a small army of private detectives and thugs). This is what led up to the Mussel Slough shootout, but that was only the beginning of a decade and a half of outlawry and social discontent directed at the Southern Pacific in the Valley.

Another Canadian comes into this, Christopher Evans, a San Joaquin farmer born in Bells Corners just outside Ottawa, who lost his farm when he contracted to sell his crop in San Francisco and the railway wiped him out with an increase in haulage rates. At about this time, he met John Sontag, a young man who had been fired by the railway after his leg was crushed between two rail cars. This was the Evans-Sontag gang responsible for at least four train robberies in the Valley between 1889 and 1892. Their daring crimes and even more daring escapes and shootouts captured the public imagination (a public largely sympathetic to robbing the robber barons) even as the railway detectives and marshals relentlessly hunted them. Sontag was finally shot to death at the Battle of Stone Corral near Visalia in 1893 and Evans captured (badly shot up).

As Richard Maxwell Brown writes in No Duty to Retreat, Values and Violence in American History and Society,

In Chris Evans and John Sontag, California's Central Valley had its own two-man version of Jesse James as social bandit Evans and Sontag gained widespread sympathy for their repeated robberies of Southern Pacific trains in 1889—92. As both glorified and resister gunfighters, the antirailroad lawbreaking of Evans and Sontag was a surrogate expressing the seething resentment against the Southern Pacific by peaceful, law-abiding residents.

Evans was released from Folsom in 1911 and went to live with his daughter in Portland, Oregon, where he wrote a book, an anarchist-utopian fantasy called Eurasia. The action takes place in the year 2000. There is no plot. The narrator arrives in an unknown country governed on socialist principles and proceeds to visit every one of its 13 government ministries plus the national bank and a prison. It begins:

One pleasant afternoon in the month of May, 19—, I launched my boat, and after rowing about half a mile from shore I shipped my oars, stepped the mast, hoisted sail and reclining on a cushioned seat at the stern with my hand on the tiller, I waited for a breeze to spring up, and whilst so doing I fell asleep. How long I slept I know not, for when I awoke my boat was close to shore, and to my' astonishment I was in strange waters.

In 1891, in the middle of the Evans-Sontag campaign, the famous Dalton Gang (more famous for its depredations in Oklahoma and the midwest) popped up in Tulare County. One of the brothers had a ranch near Visalia. On February 6, they robbed a Southern Pacific train near Alila during which the train’s fireman was shot to death in cold blood (the baggage car guard jumped out and disappeared into the brush taking the combination to the safe with him). A year later, the details of his robbery were published in a gory potboiling nonfiction book The Dalton Brothers and their Astounding Career in Crime.

It was this particular robbery and the book that inspired Dan McCall in 1896.