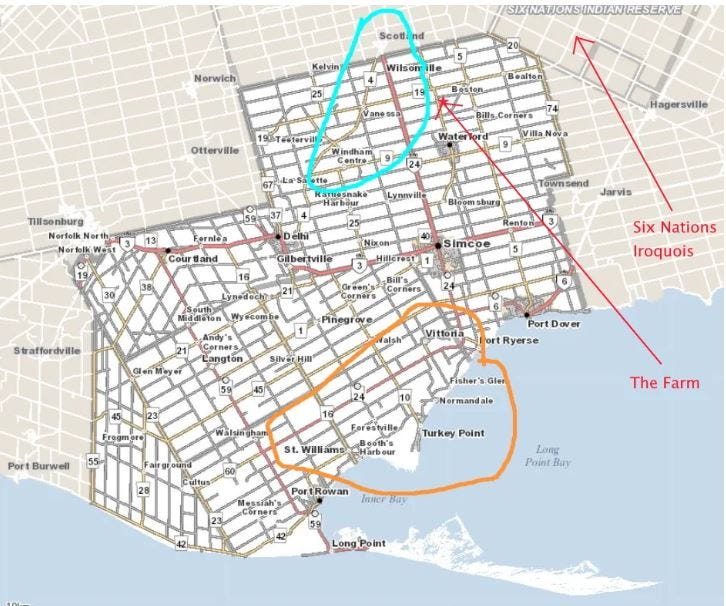

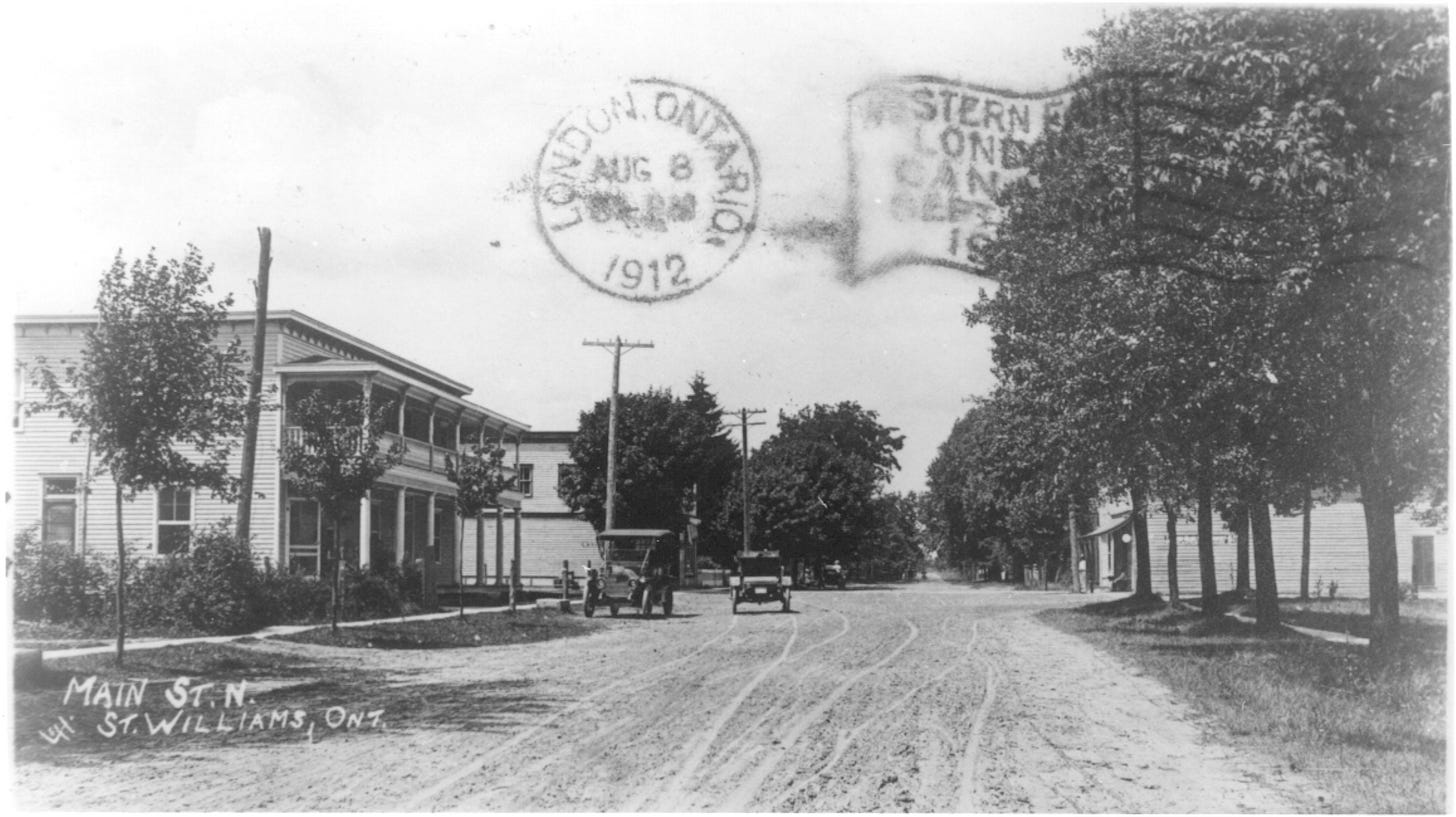

My great-grandfather, a storekeeper-poet in the village of St. Williams on the north shore of Lake Erie, killed himself in 1914 with an overdose of laudanum at the age of 51. He had been accused of alienating the affections of a neighbour’s wife and a court case was imminent. I wrote an essay about this, which you can read here. 1

That essay is a product, a distillation, and an interpretation. So much lies beneath. So much remains unknown, perhaps unknowable. John Brock died in March, 1914. Some time after that the facts of the case went underground. Brock’s official cause of death was “opium poisoning,” but his wife Sarah lived to 101 claiming he died of diabetes. My grandmother, his daughter, who was 18 at the time of his death, never said a word to contradict this.

Shame and silence ruled small town Ontario in those days. There were strict and narrowly defined social codes. Accusations of irregular behaviour ruined lives. My grandfather had two teenage daughters with reputations to preserve. Today, the Kevin Spaceys of the world can cheerily go to court and defend their sex lives by endlessly talking about their sex lives. In 1914, the mere suggestion of appearing in court to answer for unseemly acts was catastrophic. Suicide doubled the stigma. Even in the 1990s, when I interviewed elderly people in the village, their reluctance to speak — “We don’t talk about those things” — was tinged with a strange fear.

In 1987, by the usual circuitous routes secret messages take to find their intended recipients, my mother got wind of the story, not the whole story, but a partial, biased version. “Why, Jeanie! I thought you knew!” I’m sure she longed to race over to her mother’s house in Simcoe and get the truth but was afraid to break the glass bell of secrecy so long preserved. Finally, she appointed me as go-between.

It was August. My grandmother, Kathleen Ross, born Kathleen Brock2 in St. Williams in 1896, was 91 and still living alone amid her gardens. I sat with her in the parlour off the kitchen, great windows giving onto the gardens, floor-to-ceiling bookcases. When I broke the uncomfortable preamble of small talk and family gossip with the question, she seemed relieved. Then it all came tumbling out, rueful, incensed, affronted, bitter, and full of love.

She was 18, the court case was impending (within the week). He came home from work, she said, kissed his two daughters, and repaired upstairs to what was called the “school room” where he sometimes gave language lessons to village children. Later, he was restless, getting up from bed and wandering out of the room, then back. Sarah, his wife, said, “John, are you drunk?” Which seems comical but makes sense given that laudanum is a mixture of alcohol and opium, the alcohol taking effect before the opium kicks in. Then it began to dawn on the household that something terrible was wrong.

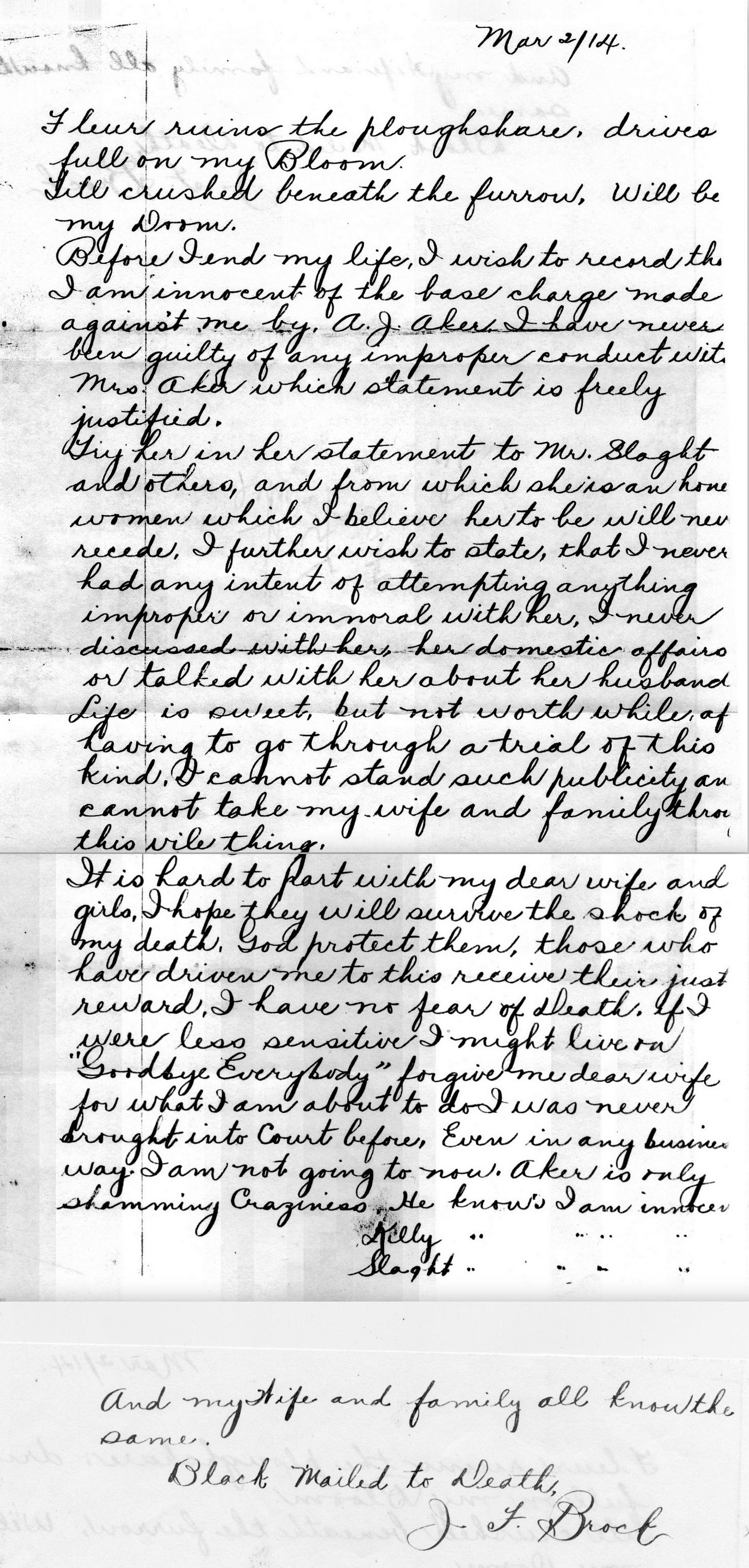

A doctor was sent for but seems not to have arrived in time. One story I heard is that a daughter of his accuser, a trained nurse, was the first medical person to arrive. Another story is that the men of the village gathered in the wide hallway and took turns forcing him to walk up and down. Nothing availed. At some point, my grandmother crawled into bed beside him and held him, pleading, “You can live if you want to.” She remembered him at the table writing the night before and it twigged in her mind that he had been writing a suicide letter, so she asked him where the letter was and he said or somehow indicated that it was under the pillow, and she got it. Then he called out, “Sarah, Sarah.” His wife’s name, his last words before dying.

My grandmother had once memorized the entire text of the suicide letter, but now she only remembered lines from a poem he had quoted and a sentence about not being able to drag his wife and daughters through a trial of this kind. The poem was Robert Burns’s “To a Mountain Daisy” (I have the copy of Burns’ poems that Aunt Maggie owned, probably the copy he read), easy to identify from my grandmother’s slightly forgetful recitation.

Stern Ruin's ploughshare drives, elate,

full on thy bloom,

Till crush'd beneath the furrow's weight,

Shall be thy doom!But the letter had disappeared. My grandmother’s memories were unbearably tantalizing, a garbled semblance of the real thing. Where did she think it had gone? Oh, she didn’t know. She thought cousin so-and-so had kept it. I phoned him that night, but it was well and truly gone. I couldn’t quite credit how woefully inept my family was at keeping its own history straight. Though perhaps the ineptitude was intentional at some level. What a shame culture fears is exposure of any sort. One does not want to be talked about.

Maybe five or six years later, I hit upon the idea of tracking down elderly people who had been living in the village. There wouldn’t be many; it was a tiny village to begin with and most would be dead. But I am the kind of researcher who is always saying let’s try this — you never know. I was living just outside Saratoga Springs, NY, at the time. I went back to the farm in Ontario frequently and started haunting the local old folks homes. Mostly I got more names to track down. I even started doing cold calls, sitting up of an evening in my study, dialing St. Williams numbers. Mostly, I got nothing. None of the people I talked to had lived in the village in 1914. There were no stray bits of gossip. But it was pleasant talking to them and listening to their memories.

Victor and Ione Leedham came up on my list. I dialed their number and an elderly gent came on the line. I had to explain who I was and what I wanted three or four times. I could almost hear his mind struggling to readjust for context, drawing lines between a voice on the phone and something that had happened 80 years before when he was a boy.

“Oh, no,” he said. “We don’t know anything about that.”

I felt a twinge of excitement, but also the usual frustration. I could tell from his voice that he knew what I was talking about, knew something, but he was never going to open up to me. I persisted. I went through my spiel again, emphasizing that it was my family story and implying that I had some right to whatever he might recall. Not harsh or argumentative, but insistent.

“I was a boy,” he said. “I don’t remember anything about it.”

“What about your wife,” I asked. “Do you think she’d remember anything?”

“The wife,” he said, as if I had just reminded him. “Oh no. She doesn’t remember anything.” He paused, then, thinking. “The wife, she has a letter —”

My adrenalin started to pump. Life is poetry. Repetitions are full of meaning. I had not mentioned anything about letters. The word “letter” came from somewhere else, a deeper level of our shared reality.

“Your wife has a letter that has something to do with my grandfather?” I prompted.

But he was going backward, away from me. “No. No, I don’t think there’s a letter.”

“Victor,” I said, “would it be okay if I talked to your wife?”

Ione came on the line, just as gentle and mistrustful as Victor had been. “Oh, no,” she said. “I was only a little girl. I was four years old.”

But there was something in her voice, something in the torque of the entire conversation (that perhaps I won’t be able to get across here), that told me I had lucked into a magical convergence.

“Victor said something about a letter, that you have a letter.”

“Oh, no. There isn’t a letter.”

“You’re sure,” I asked.

“Oh, yes.”

And then I made this little speech, which even at the time I thought was brilliant. It was clear to me that somehow we were talking on multiple planes at once, we were talking about what we were not talking about, the taboo and unspeakable, and we all three knew it.

“Ione,” I said, “if you did have a letter, is there any chance I could see it? If I drove up there, would you let me look at it?” I was careful here not to ask for the letter itself, feeling intuitively that that would be a step too far. Once again, the important communications were unspoken.

“There isn’t a letter.”

“But would it be okay if I did drive up and stop for a visit? Not right away. But at some point?”

Two months later, I drove over from the farm to the Leedhams’ little house on the outskirts of St. Williams. They were a sweet, white-haired couple, a bit shy, but comfortable and easy with one another, as if they moved in sync in the same space, as it were. There wasn’t any need to tell my story again. Ione came to the door with papers in her hand, John Brock’s original suicide letter and photocopies she had made for me to take. I held the letter in my hands, knowing I would never get another chance, but also content with that.

We chatted. I was still nosing around. Her father had been a butcher. They lived “across the street” from the Brocks (looking at old village maps, I have never been able to figure out exactly where she meant). But how did she get the letter? It was in her family Bible. Maybe she had more to say on that than she said — that was ever the nature of our conversation. I still have a difficult time imagining how the letter got from my grandmother’s hands in March, 1914, into the Ione’s family Bible across the street, a family totally unrelated. But then nothing could be more bizarre than my actually finding Ione and the letter anyway.

I said goodbye. It was generous and kind of her to let me see the letter. In our talk, she had reiterated the taboo. “We don’t like to talk about things like that.” Almost superstitious, fearful of cosmic consequences. Both Victor and Ione are dead now. I hope their daughters kept the Bible and the letter.

Here is a copy of the letter. Ione’s photocopy turned the original one-page (signed on the back) into two pages and cut off a few letters on the right. I also darkened the text. Brock, obviously under pressure, misquotes the Burns poem. A. J. Aker is the man bringing the complaint against him. Kelly is W. E. Kelly of Kelly and Porter in Simcoe, Aker’s lawyer. Slaght is Brock’s lawyer.

The Possum

Here is an essay about my great-grandfather John Brock who fancied himself a poet and committed suicide in March 1914. The essay was published a while ago in the print magazine Canadian Notes & Queries (Issue 115, 2010), so not likely to have been seen by anyone recently.

Pete & Jigs, 1918

Here’s a little essay about pandemics, frontline workers, and courage. My grandparents’ generation lived through that earlier pandemic, the 1918-19 flu, which also came in waves, each different, the worst hitting in October 1918. Thinking of this and our current situation, I wrote an essay about my grandmother who was a student nurse in Toronto General …

Sydney, I wouldn't take bets on which of us has the most striking family members. What I think is that it just takes a person, you or me, to identify and frame the stories so other people can catch the gleam.

How is it that your writing can sometimes be ironic and violent and yet can also bring me to tears?